Liam O’Reilly, a recent graduate from the University of Maryland, told The New York Times that he had applied to 50 employers. He was looking for a job as a paralegal or as a researcher for a policy organization or as an administrative assistant. He got a few interviews and no offers. So he took a minimum-wage job selling software.

Liam O’Reilly, a recent graduate from the University of Maryland, told The New York Times that he had applied to 50 employers. He was looking for a job as a paralegal or as a researcher for a policy organization or as an administrative assistant. He got a few interviews and no offers. So he took a minimum-wage job selling software.

“Had I realized it would be this bad,” he said, “I would have applied to grad school.”

My Number Three Son was due to graduate this year. But when he got accepted into a five-year BA/MBA program at his school last month, I encouraged him to do it. Like Liam O’Reilly, his prospects for employment are limited. They might not be better next year, but at least he can approach the market with another year of learning and an MBA to boot.

In 2006, when I wrote Automatic Wealth for Grads… and Anyone Else Just Starting Out, the economy was still bustling, American businesses were going strong, and unemployment was low.

Back then, any kid fresh out of college could have his pick of good jobs in preferred locations with plenty of perks.

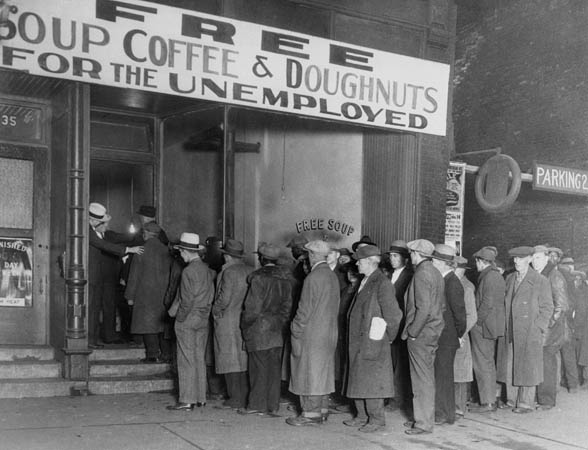

Today, the economy is a mess, businesses are floundering, and unemployment is record high. As a result, college graduates are taking what they can get.

Many, not finding jobs, are forced to continue living with their parents.

(The situation is considerably better for kids with engineering and computer degrees, but otherwise the landscape looks bleak.)

Recently, I received this e-mail from a young reader:

“My name is Eric Ryczek. I am a sophomore at Drake University in Des Moines, majoring in International Business and Finance.

“I am currently reading your book Automatic Wealth for Grads — which my uncle bought for me as part of my 18th birthday/graduation present — and am loving every minute of it. And last week, he forwarded me an excerpt from your book The Pledge, and I am eager to read the rest of it.

“But I’m wondering if I am still too young for The Pledge, even though I am trying to do everything I can and gain as much knowledge as I can now to invest in my future. And I am hoping you will tell me that the book is beneficial for anyone, no matter how old they are.

“I know you have millions of e-mails to respond to, so if I do not get a response I will purchase the book anyway. I think it will be a good investment for my future.

“Hope to hear back from you.”

I’m worried for Eric’s generation. They are facing, without a doubt, the worst job environment since the Great Depression.

The economy is in shambles and, despite what the government is saying, it’s not getting better. In fact, it will get worse. Possibly a lot worse.

The idea that there are more good and qualified people who want to find jobs than there are appropriate jobs for them is a myth (perpetuated by academia). The opposite is true. There are plenty of good jobs, but most people who apply for them are unqualified to fill them.

The idea that there are more good and qualified people who want to find jobs than there are appropriate jobs for them is a myth (perpetuated by academia). The opposite is true. There are plenty of good jobs, but most people who apply for them are unqualified to fill them.

Liam O’Reilly, a recent graduate from the University of Maryland, told The New York Times that he had applied to 50 employers. He was looking for a job as a paralegal or as a researcher for a policy organization or as an administrative assistant. He got a few interviews and no offers. So he took a minimum-wage job selling software.

Liam O’Reilly, a recent graduate from the University of Maryland, told The New York Times that he had applied to 50 employers. He was looking for a job as a paralegal or as a researcher for a policy organization or as an administrative assistant. He got a few interviews and no offers. So he took a minimum-wage job selling software.