The last time I was in Las Vegas for more than a business meeting was when my children, now grown and with children of their own, were in high school. We spent a week there, marveling at the mega-hotels, getting lost in the cavernous casinos, riding the rollicking rides, shopping in the scenic super-malls – generally swept away by the sounds and scintillations of that surreal, synthetic city.

Las Vegas offers a special kind of fun. It won’t give you the expansive fun of trekking the desert or the aesthetic enjoyment of walking through Rome. It’s more like a B movie or a Keno girl cinched up in lace and silk stockings: a type of sensory indulgence that you can’t be proud of but you don’t feel ashamed of either.

I remember the reaction of Son Number Two, who was reading Will & Ariel Durant’s history of ancient Rome at the time. Shaking his head, he kept saying, “This is surely the end of the American Empire.”

One can’t deny that thought. In terms of size, sumptuousness, and spectacle, there is no other place in the world like Las Vegas. (I’ve not been to Dubai.) The vast, opulent malls America pioneered in the early 1990s prepare you for the size of it – and Disney World/Land can give you an idea of how friendly replica environments can be. But they are but cartoons to the masterpiece of marketing and merchandising that is Las Vegas. Las Vegas is a one-and-only and offers a sui generis experience to all who visit.

A World Unto Itself

Take the Bellagio…

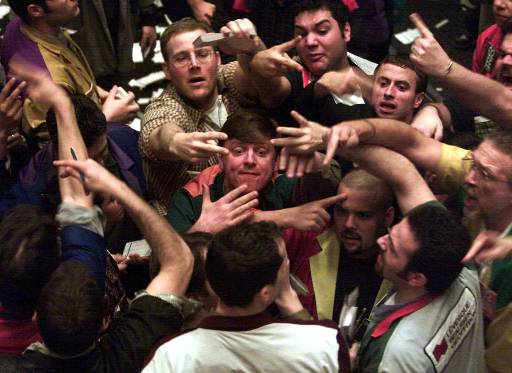

The casino is larger than several football fields and jam-packed with roulette tables, poker bars, and one-eyed bandits. It has its own mall… a deluxe promenade that rivals Worth Avenue or Rodeo Drive, featuring the same deluxe stores (Gucci, Armani, etc.) you can now find in every major tourist city around the world.

Walking into the lobby you can’t help but be awed by Dale Chihuly’s Fiori di Como, a glass sculpture composed of 2,200 hand-blown glass flowers and covering 2,000 square feet of the ceiling.

In addition to dozens of casino-side eateries and buffets, the Bellagio offers at least a dozen first-class restaurants, bars, and nightclubs within its buildings, as well as several theaters.

Outside, a water show takes place every 30 minutes. It is a wonder of science – computer engineering and plumbing – that provides a spectacular, three-dimensional representation of show tunes and opera that ranges from charming to breathtaking.

And there is the Bellagio Fine Art Museum, which displays, I was surprised to discover, large (if not great) works by Picasso and other 20thcentury masters.

The first half of the Bellagio cost something like $1.6 billion in the mid-1990s. The second half, built later, cost more.

Defining Our Terms

Three billion dollars is a lot to risk on a new business. But was this a gamble?

Were the people that invested in the Bellagio back then gambling? Were they, like the people sitting at the casino’s blackjack tables and slot machines, risking their money against the odds?

Or would you call it an investment? READ MORE