When I first read Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari, I read it quickly. It was the selection of the month for my November book club – and by the time I got to it, I had less than two days to go through it.

No problem. I arrived at the Cigar Club, book in hand, with plenty to say. And most of that was a mixture of admiration and dismissal. Among other things, I said that it was “the best-written book that told me things I already knew.”

Two weeks later, I listened to it on Audiobooks, and I loved it. And now I’m reading it again… and I’m thinking it may be one of the best books I’ve ever read!

Each chapter is a book in itself. And each section of every chapter contains at least one idea that feels big and new and important. This is a book that I will read over and over again.

I felt the same way about Pride and Prejudice when I first read it, which was 12 or 15 years ago. I’ve read it twice since then, and I’d be happy to read it again today.

But had I read Pride and Prejudice as an undergraduate, I might have dismissed it as superficial and melodramatic. I know I felt that way about Henry James’s Portrait of a Lady and The Ambassadors when I read them for Dr. Powers at the University of Michigan. I pretended to admire them because he did, but they felt insignificant to me then. (“Brilliant writing about trivial human affairs,” is what I said in my journal.)

I don’t feel that way about those two novels now that I’m older and less cynical. Quite the contrary, I think they are brilliant and deep.

And that’s one of the problems with lists of the “best” books. The pleasure we get from books depends greatly on the level of intellectual and emotional sophistication we have when we read them. On the one hand, a book that strikes us as luculent in our youth might seem dim or even dimwitted decades later. On the other hand, a book that bores us in high school might thrill us in our middle age.

The same can be said of almost any aesthetic object. That painting of the young girl with the huge brown eyes that swept us away when we first saw one in Woolworth’s when we were nine years old now looks like the intentionally bathetic work of a commercial panderer.

I’m not suggesting that there is no such thing as bad, better, and great books. I’ve made the point elsewhere that I believe very strongly that the potential pleasure and elucidation we get from a book depends primarily on its intrinsic qualities. As a general rule, books that are broader and deeper and also subtler tend to get better the more you read them because they are better. They are better because they have complexity, depth, and subtlety, qualities that are enhanced by rather than diminished by repeated exposure.

What I’m saying is that best-books lists should be seen as what they are: the temporary feelings of one person – the list maker – at a particular time.

That said, here is my list of “best” books that I read (or reread) in 2018:

- Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari

- The Good Earth by Pearl Buck

- Brief Questions to the Big Questions by Stephen Hawking

- The Sheltering Sky by Paul Bowles

- Beyond the Grave by Jeffrey L. Condon

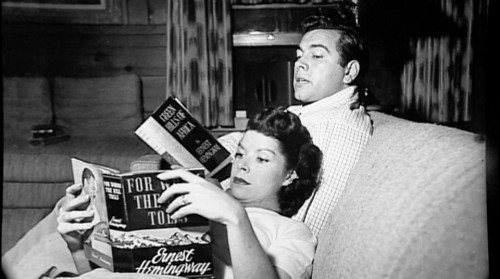

- For Whom the Bell Tolls by Ernest Hemingway

- Fox 8 by George Saunders

- 21 Lessons for the 21stCentury by Yuval Noah Harari

- Dress Her in Indigo by John D. MacDonald

- The Soul of America by Jon Meacham