My life changed dramatically and immediately when, in 1982, I decided to make “getting rich” my number one goal.

My life changed dramatically and immediately when, in 1982, I decided to make “getting rich” my number one goal.

Within a few weeks of that decision, I convinced my boss to raise my compensation from $35,000 to $75,000. A year later, I was a bona-fide millionaire.

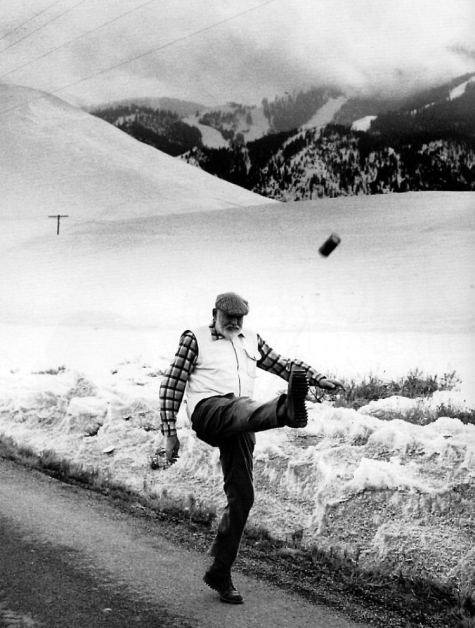

My status changed too — from just another good employee to a junior partner and employer of hundreds. This made me more confident. And that confidence had a noticeable effect on everyone I dealt with. They took my opinions more seriously. They gave me more respect. Most memorably, my lifestyle changed. Instead of eking out a modest living, paycheck to paycheck, I was able to buy a car without asking how much it cost.

But making this change happen had two negative consequences:

1. I gave up thousands of hours of good times with friends and family.

2. I did a few things I wish I hadn’t.

When I set that goal, I knew there were more important things in life than money. But I suspected that I would be more likely to achieve it if I made it my number one priority. That turned out to be terribly true. There is enormous power that comes from saying “I will put this goal above all others.” It is impossible to understand that power until you have experienced it.

Most people won’t even dare to try. And maybe that is because most people have more sense than I had back then.

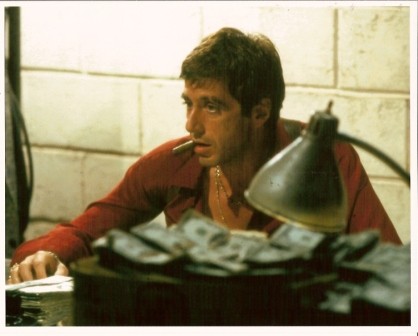

I didn’t recognize how monomaniacal I would become. I didn’t anticipate how willing I would be to put my family second. Most of all, I didn’t realize that I would be making some ethical concessions along the way. When my partner and I were accused of misleading advertising, I was actually shocked. All of our copy had been run by lawyers. It was accurate to the letter of the law. How could they call it misleading?

Because some of it was.