Word for the Wise

Leonine (LEE-uh-nine) = of or relating to a lion. Example as used by Sax Rohmer in the 1915 crime novel The Yellow Claw: “In the leonine eyes looking into hers gleamed the light of admiration and approval.”

Quotable Quote

“The ability to simplify means to eliminate the unnecessary so that the necessary can speak.” – Hans Hoffman

From My “Work-in-Progress” Basket

Principles of Wealth: #12 of 61

The term “value” is widely understood in theory but rarely in practice. Value denotes that which you can appreciate and benefit from, both now and also in the future.

Anything that is valuable to you can be said to be a value. Friendship, for instance. Or fidelity. Or art. Or dance. Or music.

Politicians value power and loyalty. They seek to acquire as much of it as they can as they rise through the political ranks so they can wield it when they are on top.

Performance artists value approval and use their energy and creativity to create the largest possible base of fans.

Professionals – doctors, architects, and plumbers – value their reputations and work hard to not only gain but also preserve and improve them by providing high quality service and personal care.

Most healthy minded people understand that wealth (and even net investible wealth) has no intrinsic value. Its value is dependent on its ability (or perceived ability) to be exchanged for those other values: friendship, loyalty, power, and admiration, to name a few.

Mini Philosophy Lesson: Aesthetics*

Most people think of aesthetics as the study of beauty. But it is a bit broader than that. The word derives from the Greek term to denote perception, feeling, or even sensation.

Plato had an idealistic view of aesthetics. He believed that there was a perfect form of the beautiful – generally and specifically. A bed, for example, was an imitation of an ideal thing, a “Form” or paradigm, almost like an abstract blueprint of what a carpenter might build. The bed that the carpenter actually built was beautiful or not to the degree that it replicated some ideally beautiful bed that exists in some other dimension. In his ideal word, only representational art would exist, and its purpose would be didactic: to teach viewers what truth and beauty look like.

Aristotle, perhaps the greatest of all philosophers, was not an idealist. He did not believe that there was some perfect bed in some ideal world that real beds and paintings of beds should imitate. It was enough for him that the painting of a bed should look as much like its earthly subject as possible. His approach to aesthetics was to identify the best expressions of art and compare them. From that, he made observations that could be used by critics (for evaluation), viewers (for appreciation), and artists (for creation).

Most of the ideas we have about aesthetics today can be said to have originated in the writings of either Plato or Aristotle. But there was a twist added at the beginning of the nineteenth century with the advent of “art for art’s sake.” This view held that art should exist solely to be beautiful. It need not have the pragmatic/didactic purposes that Plato and Aristotle suggested.

I don’t know of a philosopher who has made this claim, but I believe that much of aesthetics is actually the basis of ethics. At the bottom of many ethical preferences – once you cut through the skimpy rationales – is some deeply held feeling about what is ugly and what is beautiful in human behavior.

*From my book How to Speak Intelligently About Everything That Matters”.

https://smile.amazon.com/Speak-Intelligently-About-Everything-Matters

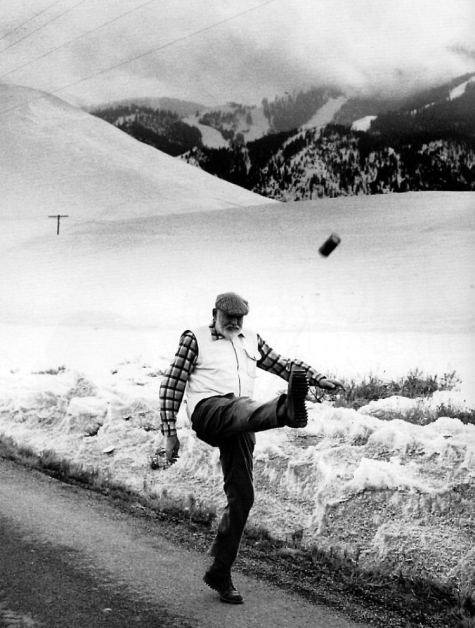

Look at This…

https://biggeekdad.com/2014/02/rhapsody-blue-harmonica-kid/