From Russia with Love

By Ian Fleming

First edition April 8, 1957

253 pages

And…

From Russia with Love

By Ian Fleming

First edition April 8, 1957

253 pages

And…

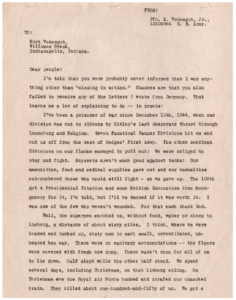

Until I came across this in Letters of Note, I had no idea that Kurt Vonnegut was a prisoner of war. This letter to his family explains a lot about his view of war and the world, as expressed in his novels.

To read the entire letter, click here.

It’s Your Ship

By D. Michael Abrashoff

Originally published May 22, 2002

240 pages

This book was published 20 years ago. I happened upon it in a used bookstore last week. It’s a quick read because Michael Abrashoff is a good storyteller and he has a good story to tell: his experience in taking over as commander of USS Benfold, one of the worst-run ships in the Navy. Abrashoff comes across as smart and experienced and accepting of his limitations. He also has a good sense of humor.

I recommend It’s Your Ship for anyone that is in a position of taking a leadership role in an organization that is established and set in its ways. I, of course, particularly liked the observations that I agree with, such as:

“The thing about rules and policies is they become very hard to fix once they are put in place. Both the people who put them in place and the people whose jobs it is to exercise them become highly motivated advocates of the policies. Even if the policies originally made sense, they become very hard to change. When you try to change something but can’t, you start becoming a tenant and stop being an owner.”

Click here for a short (5-minute) read about the book.

And here to watch an interview with the author.

And here to watch him making a presentation at a conference.

Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End

By Atul Gawande

282 pages

First published Oct. 7, 2014

Someone must have recommended it. And I must have asked Gio to order it for me. It appeared on my desk last Monday.

I wondered whether it was suggested as something I should read after writing about my stroke. I couldn’t remember. But I liked the look of the book. The size, the thickness, the cover design. And I liked the title. Being Mortal promises a philosophical treatment of one of the deepest questions we can ask ourselves. And the subtitle – What Matters in the End– promises a big and useful answer. An idea that could change or advance my view of death.

It didn’t take me many pages to realize that the author had a somewhat different objective in writing the book. For him, the question is about geriatric medicine: What should our goals be in terms of providing health care to the old and dying?

Doctors, Gawande says, are too often uncomfortable dealing with their dying patients’ understandable anxieties. They choose, instead, to give them treatments that don’t improve the quality of their remaining years and can make things worse.

One of his most provocative arguments is that hard-won health and safety reporting requirements for elder care facilities might satisfy family members but ignore what really matters to the patients. Despite the popularity of the term “assisted living,” he says, “we have no good metrics for a place’s success in assisting people to live.” And as he points out, a “safe” life isn’t what most people really want.

Although, Gawande identifies no perfect solutions to the problems he presents, the presentation is important and stirring. If nothing else, reading this book will help you better prepare for your own or your loved ones’ final days.

Critical Reception

* “In his newest and best book, Gawande has provided us with a moving and clear-eyed look at aging and the harms we do in turning it into a medical problem, rather than a human one.” (The New York Review of Books)

* “Gawande’s book is so impressive that one can believe that it may well [change the medical profession].” (Diana Athill, Financial Times/UK)

* “A needed call to action, a cautionary tale of what can go wrong, and often does, when a society fails to engage in a sustained discussion about aging and dying.” (San Francisco Chronicle)

Click here to watch a video review of Being Mortal.

The Haunting of Hill House and Their Eyes Were Watching God

If the book we choose to read is thin – say, less than 350 pages – the Mules will often read a second book. I don’t get it. It seems to me that one book is more than sufficient to fuel a good discussion. But I don’t complain. The elder Mules, those that make these decisions, are wise. I trust them.

In October, we read two books, neither of which I had even heard of before: The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson, and Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston. Usually, when we read two books, there is something that connects them. (In November, for example, we are going to read From Russia With Love and a biography of Ian Fleming.)

This time, as near as I could tell, there was no connection. The subject matter was different. So were the themes, styles, and genres.

But there was one thing that was true of both of them: They are superbly written.

The Haunting of Hill House (1959)

By Shirley Jackson

246 pages

The Haunting of Hill House is the story of six people that spend time in a supposedly haunted house. They include Dr. Montague, an occult scholar looking for solid evidence of a “haunting”; his wife, a believer in spirits; Theodora, a feisty young woman; Luke, the future heir of the house; and Eleanor, a fragile young woman that supposedly had experiences with poltergeists when she was young.

As the days pass, odd and scary things begin to happen. Mostly to Eleanor, who is the central character through which we come to understand the others.

We began our discussion by trying to identify the book’s genre. Was it a gothic horror novel? Or a psychological thriller? We could not agree. And so, we went on to discuss other matters. The novelty of the story, the development of the characters, the quality of the writing – and we disagreed about all that too.

That is not exactly right. Nearly all the assembled Mules, and those attending by Zoom, felt that it wasn’t a good book. The plot was not surprising. The characters were cliché. There were none of the twists and turns and surprises they wanted from a story of this type. It was just not interesting. There were, however, two Mules (GG and yours truly) that felt differently. We thought it was a very good book. And we thought it was very well written.

In support of our argument, I accused my fellow Mules of being dense. GG, averse to ad hominem attacks, made a case for the literary quality of the novel by reading the first paragraph out loud…

“No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.”

Everyone had to admit: That was damn good writing.

Critical Reception

Although outnumbered at the meeting, GG and I weren’t the only critics that recognized the quality of this book. In The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Damon Knight selected it as one of the 10 best genre books of 1959 and declared it to be “in a class by itself.” In 2018, The New York Times polled 13 respected horror novel writers to choose the scariest book of fiction they had ever read. Two of them, Carmen Maria Machado and Neil Gaiman, chose The Haunting of Hill House.

But the ultimate praise came from the ultimate horror fiction writer of our time, the one and only Stephen King. He called it “one of the finest horror novels of the late 20th century.”

Interesting

Shirley Jackson decided to write the book after reading about a group of 19th century “psychic researchers” who had studied a “haunted” house and reported their supposedly scientific findings to the Society for Psychic Research. After the book was published, she said, “No one can get into a novel about a haunted house without hitting the subject of reality head-on; either I have to believe in ghosts, which I do, or I have to write another kind of novel altogether.”

Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937)

By Zora Neale Hurston

219 pages

After defending The Haunting of Hill House for an hour or so, it was to GG’s and my relief that the Mules were unanimous in liking Their Eyes Were Watching God. They liked the story. And the main character. And the minor characters. And the themes. And the book’s literary qualities.

An example of the writing – the first paragraph:

“For some they come in with the tide. For others they sail forever on the horizon, never out of sight, never landing until the Watcher turns his eyes away in resignation, his dreams mocked to death by Time. That is the life of men.”

Their Eyes Were Watching God is the story of Janie Crawford’s life, from “a vibrant, but voiceless, teenage girl into a woman with her finger on the trigger of her own destiny.” It is, from what I’ve been told, a standard text for high schools today. It’s considered important in its exploration of feminism and the African American experience in Florida in the early 20th century.

Critical Reception

Initially, the book was slammed by Richard Wright and other leading figures of the Harlem Renaissance for perpetuating a stereotypical view of African Americans that, in Wright’s words, “eat and laugh and cry and work and kill; they swing like a pendulum eternally in that safe and narrow orbit in which America likes to see the Negro live: between laughter and tears.”

Hurston’s reputation was restored in the Black community in 1975 when Alice Walker published an essay in Ms.magazine (“In Search of Zora Neale Hurston”) that is largely credited with reviving interest in her work. “A people do not throw their geniuses away,” Walker is famously quoted as saying. “And if they are thrown away, it is our duty as artists and as witnesses for the future to collect them again for the sake of our children and, if necessary, bone by bone.”

The book was reissued two years later and has since appeared on many “100 best” lists.

One of the Boys

By Daniel Magariel

176 pages

Released March 14, 2017 by Scribner

It was in one of several to-read stacks in my office. I selected it to take with me on the trip to Myrtle Beach because (1) it was thin, (2) it had a bright orange cover, and (3) it had an endorsement by George Saunders (a writer I greatly admire) above the title: “Brilliant, urgent, darkly funny, heartbreaking – a tour de force.”

The Story: After a divorce and acrimonious custody battle, a man and his two sons leave Kansas for Albuquerque, where they will start a new life. The boys enroll in school and join the basketball team, while the father works from their apartment. As the weeks go by, the father’s behavior becomes suspect. As the months pass, things go from bad to worse.

One of the Boys is a good book. Compelling, insightful, and well written. It is about love and abuse, ambition and addiction, and dependence and desperation. If that sounds depressing, it is. I was in a low mood when I read it, and it didn’t cheer me up. But it did get me thinking.

Critical Reception

* “Magariel’s debut is sure, stinging, and deeply etched, like the outlines of a tattoo. Belongs on the short shelf of great books about child abuse.” (Kirkus Review)

* “Magariel’s gripping and heartfelt debut is a blunt reminder that the boldest assertion of manhood is not violence stemming from fear. It is tenderness stemming from compassion.” (New York Times)

* “Because it homes in on instances of abuse to the exclusion of all else, it risks feeling like a deposition rather than a story. Whenever the father appears, he is doing another thing that would scar a child for life. Virtually every adult is a seedy, frightening derelict to whom the boys are exposed through the father’s neglect.” (The Guardian)

The Everyday Patriot: How to Be a Great American Now

By Tom Morris

138 pages

Published June 29, 2022

This was one of two books the Mules read in September. It’s short. A quick read. And it’s well intentioned. If you are in the mood for a temporary lift in your political or social outlook, this could do the trick. But if you’re looking for something more substantial, you won’t find it here.

The Everyday Patriot is a call to action. Morris is calling on his fellow Americans to do more than simply vote and have political opinions. He wants them to join him and other “daily patriots” – even those with different views – in making America a better place for all. The way you do that he says, is through one thoughtful action at a time.

Morris believes that a citizen’s political duty goes beyond voting and having political opinions. It includes acts of charity or good will every day. If everybody pitched in and did one thing every day, it would make America a better place to live in.

Noting that we are living in a politically and socially divisive country, he calls upon us to reject negativity and embrace the core principals of the founding fathers: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness… plus equality and justice for all.

A chapter is devoted to defining these terms as they were meant in the Declaration of Independence. He also dips into Aristotle quite a bit, who, he argues, inspired the ideas of the founding fathers.

On the one hand, Morris’s call to action is difficult to criticize. He’s saying, “Come on guys. We’re all Americans. Let’s stop the hating and start being nice to one another.” On the other hand, one can imagine how well this would work in the middle of a riot in Times Square, which is about the actual state of things in America today.

Men Without Women

By Ernest Hemingway

128 pages

First published in 1927

Men Without Women is Hemingway’s second short story collection. There are 14 stories in all. Most are short and sparse, more journal entries than fully developed stories. But four of them – The Killers, Fifty Grand, Hills Like White Elephants, and In Another Country – are complete and very good.

I read it while I was in the hospital last week, nodding in and out of consciousness. It was a literary balm to soothe my ontological anxiety.

Critical Response

* Ray Long, editor-in-chief of Cosmopolitan, said that Fifty Grand was “one of the best short stories that ever came to my hands… the best prize-fight story I ever read… a remarkable piece of realism.”

* Percy Hutchinson, in the New York Times Book Review, praised the collection for “language sheered to the bone, colloquial language expended with the utmost frugality; but it is continuous and the effect is one of continuously gathering power.”

* Joseph Wood Krutch called the stories in Men Without Women “Sordid little catastrophes” involving “very vulgar people.”

Interesting

Hemingway responded to the less favorable reviews with a poem published in The Little Review in May 1929:

Valentine

(For a Mr. Lee Wilson Dodd and Any of His Friends Who Want It)

Sing a song of critics

pockets full of lye

four and twenty critics

hope that you will die

hope that you will peter out

hope that you will fail

so they can be the first one

be the first to hail

any happy weakening or sign of quick decay.

(All very much alike, weariness too great,

sordid small catastrophes, stack the cards on fate,

very vulgar people, annals of the callous,

dope fiends, soldiers, prostitutes,

men without a callus)

Hemingway’s style, on the other hand, received much acclaim. Even Krutch, writing in the Nation in 1927, said, “Men Without Women appears to be the most meticulously literal reporting and yet it reproduces dullness without being dull.”

Raylan

By Elmore Leonard

288 pages

Originally published Dec. 26, 2012 by William Morrow

Raylan, the second of two books I read this month for the Mules, is, in some ways, better than Hombre, which I reviewed on Aug. 26.

It’s a story about a tough deputy US Marshal that returns to the place he grew up in to track down some seriously bad guys. Raylan Givens is a cool cat. Affable and low key – both compassionate and lethal in carrying out his duties among the denizens of the Appalachian Mountains of eastern Kentucky.

Elmore Leonard wrote three Raylan novels based on his short story “Fire in the Hole.” This one, interestingly, was written after FX made a television series – Justified – based on the first two. (See my review of Justified, below.)

Neither the book nor the FX series is high art, but they are both smart, well written, and thoroughly enjoyable. I recommend them.

Critical Reception

* “In addition to kinetic storytelling and spot-on dialogue, Leonard has a cool wit…. Characters roll from scene to scene, urged on by self-interest and greed, bumping against one another and building up steam until they’re smashing together in orgies of violence.” (New York Times Book Review)

* “The smarter crooks give Raylan grudging respect; his fellow lawmen grant him their highest praise: ‘You’re doin’ a job the way we like to see it done.’ The same can be said of the 86-year-old Elmore Leonard.” (Wall Street Journal)

* “[Leonard’s] finely honed sentences can sound as flinty/poetic as Hemingway or as hard-boiled as Raymond Chandler. His ear for the way people talk – or should – is peerless.” (Detroit News)

So Good They Can’t Ignore You

By Cal Newport

288 pages

Published Sept. 18, 2012 by Business Plus

I came across this book while reading a young blog writer that a friend recommended. In talking about something he called “career capital,” a lesson in a course he gives on personal success, he mentioned that his partner in the course had written something by this title.

The subtitle (“Why ‘Follow Your Passion’ Is Bad Advice”) sold me.That’s something I’ve been saying in my books and on my blog posts for 20+ years.

I asked G to order me a copy, and I read it over the weekend. I thought, “I bet this Newport guy subscribed to Early to Rise when I first began to write about this.” He made all the points I made. But he arrives at his advice through interviews: asking organic farmers, venture capitalists, screenwriters, and freelance computer programmers that loved their careers how their passion happened.

It turns out that it takes some thought and effort to end up in a career that you can love. Much of what careers look like from the outside feel very different when you are on the inside, trying to make them work.

Here is some of his advice:

Note: Newport doesn’t tell you what particular skills are needed for any of the industries he studies. He seems to believe, correctly I think, that every business in every industry has its unique features.