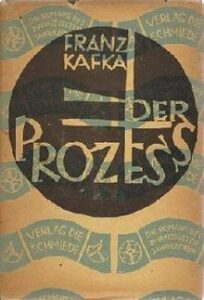

The Trial

By Franz Kafka

Written in 1914 and published posthumously in 1925

176 pages

May’s book selection for The Mules was The Trial by Franz Kafka. We don’t often read classics, but I’m always happy when we do. In some cases, I get to read an important book that I’ve never read. If I’ve read it already, it’s even better. Classic books are classics for a reason. You can’t possibly get all they offer in a single read.

Prior to this, I had read only one book by Kafka: Metamorphosis. (I think it was assigned in college.) But if ever The Trialcame up in conversation, I’m sure I would have pretended to have read it. Even in high school, I was well aware that reading Kafka – and these two novels in particular – was de rigueur for anyone that wanted to present himself as well read.

I’m not sure how to describe The Trial. It reminded me a bit of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. In both books, the protagonist is involved in the criminal justice system. In both, there is a good deal of philosophical consideration that carries along just under the action. Both Kafka and Dostoevsky have an ability to present a dark, almost fatalistic, view of the world in an unsettling but comic way.

But The Trial also reminded me of some of Samuel Beckett’s plays (Waiting for Godot, Endgame, etc.) in its soporific pace, simplicity of language, and absurdist point of view. I found myself thinking, “Okay, I get it,” after the second chapter. I almost stopped reading. But, first, I decided to watch Orson Welles’s rendition of the story on film. And I’m glad I did. It was mesmerizing and sent me back into the book with the energy to finish it.

The Plot

On the morning of his thirtieth birthday, Josef K, the chief cashier of a bank, is unexpectedly arrested by two unidentified agents from an unspecified agency for an unspecified crime. Josef is not imprisoned, however, but left “free” and told to await instructions from the Committee of Affairs.

The rest of the book is like a bad dream. For the protagonist, things go steadily from bad to worse.

The Themes

We didn’t spend much if any time on the plot. The plot, in any good absurdist or existential novel, is not the point. Our conversation was all about the themes that presented themselves continually in the reading of the book and then came back to haunt the reader after putting it down.

At one level – the most basic, I think – The Trial is about the endless tyranny of bureaucracy. But it is also very much about the existential dilemma of being human in a nihilistic, post-Enlightenment, post-religious world, where finding meaning in life is impossible, unless one can find meaning in nothingness. (An idea that Sartre, among other existentialists, made a fair case for.)

A major theme of the book, which I was surprised most of the Mules didn’t recognize, was guilt – the result of man’s original sin: being born with a self-reflective consciousness and having to deal with its constant reminders of his weaknesses and failures.

Okay, I’ll stop here. I was hoping to give you a sense of how many interesting and potentially pompous topics The Trialcould lend to any philosophical conversation, as it did to ours that evening.

Here is what I need to say. The Trial is, as advertised, a great book. Not great in the sense of “I really enjoyed reading it,” but great in the sense of “If you want to experience why Kafka is considered so important by so many smart people, you have to read it.”