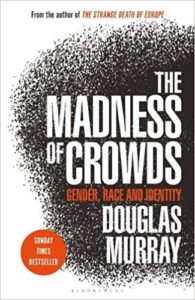

The Madness of Crowds: Gender, Race and Identity

By Douglas Murray

288 pages

Originally published Sept. 17, 2019

I’ve heard Douglas Murray on the BBC. I’ve seen him in a few debates. And I’ve had The Madness of Crowds recommended to me by friends and colleagues. But until last week, I didn’t realize that Murray was the author. It was time to check it out. So, I ordered it on my audio app and began listening.

I’ve read (listened to) about half of it so far, and I’m feeling like it’s a well-spent investment of time. The Madness of Crowds is about, among other things, some of the extreme ideas that leftists are promoting about gender and sex. And yet, in Chapter One, I learned that Douglas Murray is a homosexual.

That has given his book an extra layer of interest for me. I want to find out how he deals with the gap between his political and social conservatism and the expectations that leftists have of him as a gay man.

It’s basically the same challenge that Black conservatives have when they talk about race or any topic that has racial associations, which is basically every topic today.

The Madness of Crowds is divided into four main sections, each a look at an identity group: Gay, Women, Race, and Trans. Murray makes a strong case that contemporary ideas about and attitudes towards each group have not been good – either for the groups themselves or for the community at large. He warns that the current practices of vitriol, cancellation, doxing (a form of cyberbullying), and other forms of and ideological persecution are fueled by identity politics. And they are growing fast. In a world gone mad with tribalism, he says, and with each tribe getting its information and inspiration from different sources, we must relearn how to accept and forgive.

Douglas Murray is smart and funny in a way that I associate with my old-fashioned view of things. His arguments are, to my mind, solid. But they are delivered, as one critic put it, with such lively, razor-sharp prose that I would want to believe them even if I didn’t.

Critical Reception

The Madness of Crowds was a bestseller and “book of the year” for The Times and The Sunday Times in the UK, but it received varying reviews from critics.

Tim Stanley in The Daily Telegraph praised the book, calling Murray “a superbly perceptive guide through the age of the social justice warrior.” Katie Law in the Evening Standard said that Murray “tackled another necessary and provocative subject with wit and bravery.” Writing for the Financial Times, Eric Kaufmann said that he “performs a great service in exposing the excesses of the left-modernist faith.”

Conversely, William Davies in The Guardian was highly critical, describing the book as “the bizarre fantasies of a rightwing provocateur, blind to oppression.” And in The Times Literary Supplement, Terry Eagleton likened it to “a history of conservatism which views it almost entirely through the lens of upper-class louts smashing up Oxford restaurants.”

About Douglas Murray

Douglas Kear Murray is a British author and political commentator. He has been a contributor to The Spectator since 2000 and has been Associate Editor at the magazine since 2012. He published his first book, a biography of Lord Alfred Douglas (the lover of Oscar Wilde), at the age of 19, while he was an undergraduate at Oxford. Since then, he has published three more books on politics, history, and current affairs, including the award-winning bestseller The Strange Death of Europe: Immigration, Identity, Islam.

Here’s a clip of him talking about the connection between post-modern theory and woke thinking today.