The Blue River

By Ethan Canin

222 pages

Published in 1991 by Warner Books

Blue River is the story of two brothers, Lawrence and Edward, who, after having taken very different paths in life, are reconnected.

Lawrence, the older brother, is an itinerant worker. Edward, the younger, is a successful ophthalmologist with a wife and son. The story begins when Lawrence appears at Edward’s front door after 10 years of absence.

With a start like that, the plot has nowhere to go but where it does go: backwards towards their childhoods, where the divergence began.

Canin’s prose style is clean, but not sparse. The action is unhurried, but not turgid. The characters aren’t fully natural, but they feel true. Something that struck me as especially good: the author’s close observations of small, physical gestures and the patterns of everyday speech.

Reading it, I found myself thinking, “This guy knows how to write.” But my appreciation stayed at that level. I was never swept away by the story or astonished by the prose.

Blue River, despite its short length and clarity, is not an easy book to read. One challenge is that the story is told by Edward, a character who sees himself as successful, smart, and virtuous, but is actually self-centered and smug.

But don’t let that stop you. Canin understands Edward’s limitations. And so will Edward, by the time this story ends.

An investment of, maybe, four hours of your time in Blue River will give you a sufficient, if not abundant, ROI.

Critical Reviews

* “Blue River is beautifully conceived, full of subtle character shadings and powerful imagery. It is brilliantly plotted too, with so many twists and surprises that one hesitates to describe a single incident in the story.” (The New York Times)

* “There are a few moments when Canin might have eased off the confessional or let the reader make the connections without forcing them upon us with one or two excess lines of explanation. But in general the novel is a smooth and graceful movement through one man’s memories and self-reflection.” (Michelle Bailat-Jones)

* “If Ethan Canin’s celebrated debut story collection, Emperor of the Air (1988), was remarkable for its variations in tone, his first novel is notable mostly for its unremitting sentimentality.” (Entertainment Weekly)

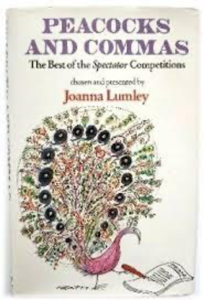

Peacocks and Commas: The Best of the Spectator Competitions

By Joanna Lumley

200 pages

Published in 1983 in the UK by Bodley Head Ltd.

Because I had failed to consider how much time one spends in an airport when reading is not possible (e.g., going through security and being questioned about the mysterious-looking refrigerator part that you brought from the States because it was unavailable in Nicaragua), I was an hour behind on my reading schedule when Nestor picked me up at the airport in Managua.

That gave me only 90 minutes to read Peacocks and Commas – which wasn’t a problem. Because Peacocks and Commas is not the sort of book one should read in one sitting, from beginning to end. It’s a literary treasure chest packed full with parodies and paragraphs, sonnets and soliloquies, epigrams, epithets, epitaphs, and other brief literary forms. And it’s much better enjoyed in brief encounters over time.

I’ll give you a few examples.

For this first one, the challenge to readers of The Spectator was to complete a poem beginning, “It looks like a season of Peacocks and commas.” The winning entry was submitted by an E.O. Parrot.

It looks like a season of Peacocks and commas,

It looks like a winter of colons and Lear;

That Abbey’s a nightmare; they never love Thomas,

Nor Jude the Obscure by Hardy the Drear.

It looks like a season of essays and Emma;

And creative writing, which means they can’t spell;

There’s The Lord of the Flies, The Doctor’s Dilemma,

And Paradise Lost, which they find sheer hell.

It looks like a season of precis and Dombrey,

And dull comprehension they don’t understand;

I dictate all the notes, each writes like a zombie,

The Sixth’s got its Melville, which ought to be grand.

Now yet one more season of grim punctuation,

Of poems they scoff at, of novels they hate,

Of screaming and chalk dust and mental frustration;

I’m retiring next summer; I can hardly wait.

The challenge here: Compose a verse about a tragic hero and a tragic heroine coping with daily matters. This brilliant little parody was submitted by a T. Griffiths.

To shave or not to shave; that is the question:

Whether ‘tis easier on the chin to suffer

The pricks and stubble of an evening shadow,

Or to take soap against a field of stubble,

And by a razor end it? To soap, to shave;

No more. And by a shave to say we end

The shadow and the thousand prickly points

That chins are heir to; ‘tis a consumption

Devoutly to be wished. To soap, to shave,

To shave; perchance to nick: ay, there’s the rub;

For in that sea of foams what nicks may come

When we have lathered all the shrinking chin,

Must give us pause. There’s the respect

That makes calamity of a morning shave,

For who would risk a stinging, painful nick,

When he might save himself the trouble daily

With a handsome beard? Who would shaving bear,

To smart and grimace under trickling foam,

But that the dread of breadcrumbs, clinging egg,

Doth make us rather shave, come the morn again…

An Epigram and an Epitaph

Coffee Percolator

by Tony Brode

Fit for a stately home that stands

In its own grounds, I see

No cause to envy house or lands –

My own grounds stand in me.

Samaritan

by Joyce Johnson

Here lies a man who often sat

And listened on the phone

To those with lives so awful that

At last, he took his own.

The challenge: Write a pretentious wine blurb. The winning selection came from the same T. Griffiths who parodied the Hamlet soliloquy above.

Hitherto synthetic wine could be robust – never svelte. Here’s one I can recommend as actually better than the natural variety; for it is silky as well as powerful, has a soft edge, large-scale yet graceful, and is both fastidious and charming.

Halcyon Harvests 1980 has an aristocratic languor with the bouquet of a great wine possessing real substance. The chemists have wrought a miracle. Free of any sulkiness or vulgarity despite its provenance, this is a true wine whose insinuating first taste has sinewy elegance and a heroic finish. Here is a classic vintage of great depth – its first taste is a minuet, its after-taste a symphony. Need one say more?

Interesting Facts

* In addition to being an author, Joanna Lumley is an activist, television producer, and actress. You may have seen her in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, The Wolf of Wall Street, and Ella Enchanted, or heard her voice in Corpse Bride.

* Lumley won two BAFTA TV Awards for her role as Patsy Stone in the BBC sitcom Absolutely Fabulous (1992-2012), and was nominated for a Tony for Best Featured Actress in a Play for the 2011 Broadway revival of La Bête. Despite having more than 100 acting credits, she has no formal acting training.

* She is a strong supporter of Survival International and the cause of indigenous rights. She narrated the organization’s documentary Mine: Story of a Sacred Mountain, about a remote tribe in India, and contributed to the book We Are One: A Celebration of Tribal Peoples.

MarkFord

MarkFord