I signed off on Tuesday saying that I might be ending the blog. “Check back with me on Friday,” I said. And here it is Friday… and I’m back!

A Quick Update

After I wrote that post, they did another CAT scan of my brain, and the head of neurosurgery determined that I was not a candidate for either of the surgical procedures I told you about.

“Why?” I wanted to know.

Because there was a blood clot in my brain that made surgery too risky. Instead of getting my artery cleaned, I could end up with a serious stroke.

The solution? Hope for the best.

That’s it. That was his advice. Those were his comforting words. I had a dozen questions, but Doctor Doom didn’t have time to answer them. After making the announcement, he pivoted like a soldier and marched out of the room, an entourage of residents and med students behind him. Several hours later, a nurse brought me a few papers to sign and then told me to go home.

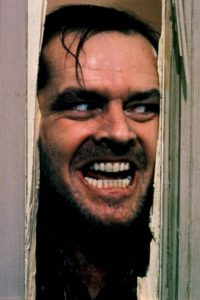

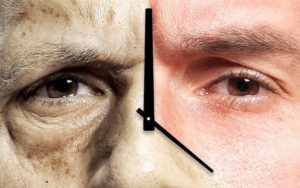

I was not happy with the doctor’s bedside manner. But I was freaked out about his diagnosis. I had an inoperable brain clot that could paralyze or kill me. My “treatment” was baby aspirin, a blood thinner, and a statin drug. None of that, I knew, would resolve the problem. I was going home with a ticking time bomb in my head, and that was that.

On Tuesday, I called the office of Dr. B, my primary physician. I told the receptionist that I wanted Dr. B to explain to K and me what the hell had happened. She gave me an appointment for the next afternoon.

When K and I met Dr. B at his office, we had at least a dozen questions for him. Before we could begin, however, he said that he had something important to tell us. When he found out that Dr. Doom had decided to release me without surgery, he said it “didn’t feel right” to him. So, he sent my records to the neurosurgeon he normally recommends for such procedures for a second opinion.

After reviewing everything – the MRI, the two CAT scans, etc. – Dr. B’s neurosurgeon (Dr. Hope) concluded that I didnot have a brain clot. But I did have an extreme occlusion in the left carotid artery that made me a “perfect candidate for surgery.”

We met with Dr. Hope yesterday afternoon. He was very likeable, very informative, and very confident that the surgery would be successful.

“But why then …?” K began to say.

“Neurosurgeons,” he explained (referring to Dr. Doom) “do all sorts of operations. But carotid artery surgeries are usually done by vascular surgeons.” (Like him.) He had done thousands of them. And mine, although riskier than normal due to the advanced degree of stenosis, was not one he was worried about.

He didn’t need to say any of that. I was so happy to hear that I could get the surgery that I didn’t really want to hear anything else.

So, this takes us back to where I left you. Tomorrow, perhaps as you are reading this, I will be having the surgery. Dr. Hope will open my neck, slice open the carotid artery, clean out the plaque, and stich me back up. The entire operation will take about an hour. I’ll come out of it with a scar and a plastic drain that will be removed after a while, and I’ll be discharged on Saturday. By Saturday evening, I will be able to return to being a grumpy old White guy complaining about getting old and pontificating about how to live a good life.

Which brings us back to the point of Tuesday’s blog post…

I’ve been using this time to try to understand what my priorities are, and what they should be. And to make changes where they are needed.

One of those priorities, as I alluded to on Tuesday, was the time and attention I give this blog.

On a list of what is most important to me, writing the blog wouldn’t make the top-10 list. But, of course, you never know how important something is until you consider how it would feel not to have that something. And so, I’ve been imagining my life without the experience of writing this blog. And it doesn’t feel all that good.

Yes, I would have extra time. It takes me three to four hours to research and write each blog post. That’s not insignificant. To give up writing the blog, though, I’d want to do something else with that time that gave me an equal or greater return.

Life Goals

I’ve told the story many times of how, when I was 31 years old, I took a Dale Carnegie course that challenged me to prioritize my goals and ambitions. It was hard for me, because I had dozens. I narrowed my list to 10. And then, with great difficulty, to three: to become a writer, to become a teacher, to get rich.

I focused on the get-rich goal first and did, in fact, go from broke to millionaire status in less than seven years. In the next seven or eight years, I did it again, and then retired to write for the business I used to run. I’ve been doing that ever since… through blogs, newsletters, emails, articles, and two dozen books, including a few bestsellers. So, I got the writing thing done.

I also got the teaching itch scratched by writing about what I had learned in my business and wealth-building career.

If I gave up writing the blog, I’d still have enough money. But I would be giving up my other two life goals: writing and teaching.

It just didn’t make sense.

When the research and writing is going well, the work itself provides a positive return. When the work is hard, I remind myself that the blog has a purpose, and I value that purpose. And that, to me, justifies the work and time.

I enjoy the research, because learning is naturally enjoyable. I enjoy the writing when I am writing well. And when I’m not, I remind myself that worthy work must sometimes be difficult. But most of all, what I like about the blog is knowing that I’m making a connection to dozens of people I know personally and thousands of people I’ve never met.

And those connections can sometimes result in an extra bonus of enjoyment – something JSN, my former partner and mentor, called the glicken, the cherry on top. I’m talking about the positive feedback I get from readers.

Since Monday, I’ve gotten many good wishes. Too many to reprint them all. But I include just a few of them below.

“Sounds like you’re getting superb care. I have no doubt you’ll bounce back and be better than ever – with new and greater insights to share.” – TB

“I just saw your blog post about your recent health challenges. I wanted to say thank you for sharing that story, and thank you for all you’ve taught me over the years. I look forward to many more lessons from you. Also sending hugs and healing wishes your way. I’m a big fan of uplifting songs in times of trial – ‘Pocketful of Sunshine’ by Natasha Bedingfield is my favorite at the moment.” – MM

“I just finished reading your Sept. 13 update and… hope Lady Fortuna holds you in her good graces with your situation…. Unbeknownst to you, you’ve been an influential figure in my life…. I value you and your thoughts. I enjoy learning whatever I can from you. And since you decided to share your situation… I decided to finally express my thanks to you.” – AG

“I just read your last, but hopefully not The Last, blog post. It does sound scary, but hopeful as well…. Here’s betting good money we, your fanboy readers, get more essays out of you soon!” – HM

“Thanks for letting us all know about your latest ‘match’ with the universe. Score: Ford – 1; Universe – 0. Looking forward to Friday – you have too much more to say… Best Wishes & Admiration” – TM

“I am a fan of yours from about 10 to 15 years back when I started reading the Palm Beach Letter for investment advice. I learned a lot from you. I am now 73 and retired…. About 5 years ago, I had a heart attack and stents were installed. I went through physical therapy and am under the care of a great cardiologist. Your life is far from over.” – TS

“I am going through a similar process. Turned 70 in April and the wheels started coming off the bus, which really pisses me off. I know exactly what you are referring to regarding thinking about death at this point…. My best wishes to you and your family and my thanks for the article as it came at a frightening moment in my life as well and I found it very helpful.” – GA

“I have admired your take on life and digested your books for years, including Living Rich. I wish you the best with the surgery and will be praying for you. Best wishes from New Zealand!” – JF

“Sending much love and prayers to you and K.” – CG

“Healthy vibes sent to you.” – TL

“Prayers your way.” – WS

“Be well Mark Michael Masterson Ford.” – TA