A Primer on US Inflation Rates

In his column on Monday, Sean talked about an important subject that I don’t know enough about: how the government handles inflation.

Let me start with this…

What I Do Know

I know that inflation, in simplest terms, is the phenomenon of currencies losing value over time. Thus, if one is speaking about the inflation rate of the US (or any other) economy, one usually speaks about the average increase of the costs of everything purchased in that economy over a given period of time.

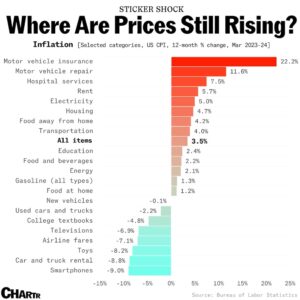

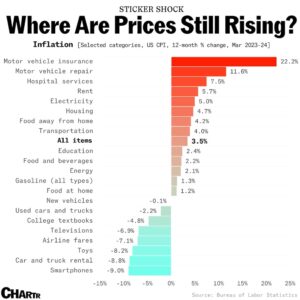

This is the chart that Sean presented on Monday:

It shows that the overall average inflation rate in the US from March 2023 to March 2024 was 3.5%. And as you can see, it is a number that is comprised of any number of inflation rates of different things bought and sold in the US economy. It includes motor vehicle insurance (which went up 22% in that 12-month period), housing (which increased by 4.7%), the cost of eating out (4%), energy (2.1%), and items like televisions, airline fares, and smartphones, all of whose prices decreased (deflated) during that same period.

In his commentary about the chart, Sean pointed out that a number of the items that had the highest inflation rates were related to the fact that in 2020/2021 there was a surge in Americans buying used (rather than new) cars, and this pushed the overall rate higher than it would have been otherwise. And since that trend was tied to specific events and not likely to last, he noted that there should be a correction in the cost of used-car-related expenses, and that the “deflation” in that market will likely result in lower overall inflation rates in 2024.

The Role of the Federal Reserve in All This

The Federal Reserve – the central bank of the United States – is a group made up of seven men appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Their primary job is to do their best to stabilize the US financial markets and keep them healthy – partly through regulations, but mostly by controlling the amount of money flowing through the economy. The main way they do that is by setting the rate at which banks and other financial institutions can borrow money from each other’s excess reserves overnight.

When the Fed’s rate is low, it is cheaper and more enticing for businesses and banks to borrow money. This supply of “cheap” money tends to stimulate the economy because lower interest rates make it more attractive for entrepreneurs to start new companies, for existing companies to increase the products and services they sell, and for the potential consumers of those products and services to buy more.

Stimulating the Economy by Lowering Interest Rates Is a Generally Good Idea, but…

There is a negative side effect of cheap money rates. And that is because of the relationship between the Federal Reserve (the Fed) and the US Treasury Department.

The Fed is just a group of presumably smart people sitting around a table, discussing dozens of factors and forces at play in the financial and business markets, and coming to agreement now and then about how much the government should charge for lending out its “money.”

The Fed has no money of its own. It is the US Treasury that has the money. But the Treasury doesn’t have all the money it needs to write checks for the tens of billions of dollars that the US government spends every year. It must cover the shortfalls by selling Treasury bonds and bills – i.e., government-backed promises to return the money it borrows with interest – to whoever is willing to buy them.

In the past, the primary customers of these promises (the primary buyers of US debt) were big, rich, profitable countries like Germany and Japan. Originally, the idea of this whole scheme was for it to be a temporary solution to a passing and pressing need – like the money needed to fight the Civil War. The idea was that this debt was going to be temporary. It would be repaid to the T-bond and T-bill holders with tax revenues. And to prevent the value of those dollars from being deflated over time, their value was officially tied to gold – gold that the government held in vaults around the country (like Fort Knox).

But that didn’t happen. The government found out that voters weren’t willing to have their taxes (and especially their income taxes) raised every time the government decided to go to war or fly a rocket to the moon or give aid to Haiti. The pols realized that if they wanted to get reelected to their cushy jobs, they had to promise to keep taxes down for the people and companies in their district.

So, that’s one big thing that happened. Despite the best hopes of those that created our taxing systems in order to fund their dreams of improving their world, there was from the get-go a growing gap between how much our legislators wanted to spend on their projects and how much gold-backed money the US Treasury had access to.

The battle between the conservative idea of spending no more than you have versus the liberal idea of borrowing money to pay for what you spend was lost – with the majority of politicians on both sides of the aisle realizing that if the Treasury Department could keep selling T-bonds and T-bills – i.e., if it could find governments and hedge funds to keep buying US debt – they could have their cake and eat it too.

There was, however, a limit to how many dollars they could lend out. And the limit was that each dollar was legally “tied to” the value of gold. By connecting dollars to the gold that the government had in its coffers, there was a limit to how large US debt could become.

This all changed in 1971, when President Nixon (supposedly a conservative) ended the convertibility of dollars to gold.Now, there was no natural limit to how many dollars the US could borrow. US debt was effectively unleashed from the anchor it had been tied to – the value of gold that the Treasury held – and that was the starting gun for a stampede of federal spending that brought US debt from $398 billion, when Nixon issued the directive, to nearly $35 trillion today!

Hold that thought while I get back to the Fed and inflation…

What happens in DC each year is that our legislators vote for a wide range of proposals, propositions, and projects to fund wars, build highways, help out single-parent families and homeless folks, fight drug addiction, bail out billion-dollar banks, and help victims of disasters in the US and all over the rest of world. And that makes them, and their constituents, feel like they are doing the right thing.

Of course, these projects, however needed or well-meaning, cost money. A gargantuan amount of money. Much more than our government has in its coffers. To pay for these programs we can’t afford, we call upon the services of the US Treasuryto bring in enough money to cover the shortfalls.

And this gets us back to inflation.

The Federal Reserve indirectly influences how much interest the Treasury can promise to pay on the T-bonds and T-bills it sells. If it raises those rates, there is less debt sold. When it lowers the rate, there are more buyers.

In essence, what the government is doing by lowering the Fed rate and thus increasing all of this borrowing of dollars that it (i.e., the Treasury) doesn’t have is increasing the amount of debt that the Treasury owes to its lenders (the T-bond and T-bill holders).

In other words, the lower the cost of borrowing dollars, the more IOUs the Treasury must print to satisfy the demand – and thus the more debt the US government will get into.

And getting into a lot of debt is never a good idea.

In 1950, when I born, the total US debt was $257 billion. In 1970, when I finished my sophomore year in college, it was $371 billion. In 2000, it was up to $5.67 trillion. And today, in 2024, it is over $34 trillion, making the US the most in-debt country in the world, more than twice as high as the world’s #2 debtor nation, China (at about $13 trillion). Click here.

How Economies Pay Down Debt

Now, I’m hardly an expert on economics. I’d call myself an interested amateur, at best. But from all the reading I’ve been doing about economics for the last 30 years, my belief is that there are only three ways an economy can pay down its debt:

1. By a miraculous surge of profitable economic innovation (very rare)

2. By a severe financial recession (like we had in 2001 and 1948 and 1930)

3. Or by a significant and sustained period of inflation.

The first option is extremely rare.

The next two are not just common but become probable once the national debt reaches a certain level. (By any realistic metrics, the US economy is already way past that.)

Back Again to the Fed

For the past 16 years, the Fed has been working hard to avoid either a financial collapse or a bout of hyperinflation by gradually easing and then tightening the money supply.

When Fed rates are low, banks and businesses are enticed to borrow more money to grow their revenues and profits. When Fed rates are high, the economy tends to slow down because fewer banks and businesses are borrowing money to invest in growing the economy.

So, on the one hand, when the economy is in a slump, the government wants the Fed to lower rates and thus boost spending. On the other hand, when borrowing is very strong, federal, corporate, and even individual debt grows, which makes for the likelihood of rising inflation.

Which gets us back to what Sean was saying in Monday’s column. He’s softly predicting that the Federal Reserve, assuming that there will be a natural decline in inflation due to the factors above, might decide to make one more reduction in the Fed lending rate before the end of the year. And if they do that, it should have a positive, stimulating effect on the economy – but not so much that it would greatly increase inflation.

And if that is true, there is reason to believe that, despite the way US debt keeps piling up, the US stock market (as well as some other US financial markets) may still have several months of growth ahead of them.

That’s what I know – and it’s a lot. But there are some questions about the government’s inflation numbers that I’ve never been able to find the answers to. So, I asked Sean to fill me in…

A Quick Q&A with Sean

Me: Sean, I am under the impression that the government inflation numbers do not include fuel and food. But they are a significant part of a middle-income family’s expenses. So how does one take account of that?

Sean’s Answer: This is… a nuanced issue. The government uses multiple models and measures of inflation to get an overall sense of price stability, which is their ultimate goal. CPI-U, CPI-W, Core CPI, PCE… the same way one looks at multiple KPIs in a marketing campaign to assess performance, the Fed looks at all of these (mainly PCE) to gauge inflation.

Core CPI does not include food and energy expenses – even though these are consumer staples – because they’re often traded speculatively in the market.

So, for example, you could have a drought, or a surge of futures buying, or a supply chain disruption cause the price of food to rise. But this rise in price doesn’t really reflect a decrease in the purchasing power of the dollar (which is what we’re really trying to assess).

Remember: Measuring the prices of things is a map, not necessarily the territory. Prices can fluctuate without it having anything to do with the stability or intrinsic value of a currency. (Which is a weird thing to say, considering that no money has intrinsic value – but I digress.)

Me: These numbers are reported every year as if they stand in historical isolation. If the inflation rate in one year is 8% and the next year it is 2%, the two-year inflation is 10%, right?

Sean’s Answer: It’s even worse than that. CPI inflation is based on an index – think a list of prices all tallied up and averaged.

If the CPI is 100 at year 0…

Then 108 in year 1… an 8% increase…

What’s 2% above that?

It’s not a CPI of 110 (10% cumulative). It’s 110.2. A 10.16% increase over two years.

Inflation compounds.

So, if we want to get back to a long-established 2% trendline, it’s possible that inflation needs to be under 2% for some time.

A recession could help with that.

Me: Isn’t it then misleading in a way to focus on the one-year rates? Take college tuition, for example. According to your chart, it was small or negative in the period measured. And yet tuition has probably gone up by a factor of 5 to 10 since I was in college. And the cost of a start-up home has gone up dramatically since I bought my first one in 1983. I paid $175,000 for a house that is probably $775,000 today.

Sean’s Answer: You’re absolutely right. And it goes even further than that. Because here’s the truth… ALL inflation data is misleading. The average person’s average experience is rarely ever “average.”

Everyone has their own inflation number. And that number is based on what they spend money on.

I had a conversation with an acquaintance about this the other day. He had been tracking his income and expenses for the last four years, and he showed me a model of the declining value of his income, which has been fixed.

But when I looked at his actual expenses… they were going down! He was spending less money on certain items and activities, but, to his chagrin, I pointed out that he was getting the same value/outcome as he did in 2020.

In other words, I explained to him that his personal inflation number was actually negative. His purchasing power has been going up.

The analyst Lyn Alden talks about this a lot. (She’s a genius.) She states that every household has its own personal Consumer Price Index.

To put it simply…

If you were a hermit who drove the same car since 1970 and only ever purchased women’s blouses and large-screen televisions… the purchasing power of your dollar has actually increased, not decreased.

That’s why, in my column, there’s a subtext of skepticism about headline inflation numbers and people’s perception of them.

Our understanding of inflation is about 100 years old. The notion that we should even strive for 2% inflation was invented by New Zealand on a whim in the late 1980s. We have a lot of different models of inflation because we don’t fully know what the best way to model inflation even is.

Me: Got it! Thanks, Sean!

What I Still Want to Know…

I came away from that conversation with a much better understanding of this very complicated subject.

Sean’s answers confirmed my belief that inflation is a serious matter and that if the Fed and Treasury make bad choices, inflation is, by definition, a way of lowering the buying power of every dollar and financial asset backed by dollars that I and my family partnership own.

He also helped me understand that some amount of inflation is inevitable and that – whether the number is 2% or some other number – the ultimate and perhaps only way to avoid economic disaster in the future cannot be achieved simply by raising and lowering the Fed’s lending rate, but by demanding that our legislators stop spending hundreds of billions of dollar each year that we don’t have.

Even after processing all of that information, though, I realized that I only half understand as much as I want to understand about inflation. And since I suspect that many of my readers don’t know much more than I do, I think I’m going to have to arrange another conversation with Sean for an upcoming issue.

Check out Sean’s YouTube channel here.