Search results

12 results found.

MarkFord.net

MarkFord.net

The open-for-inspection half-way home for my writing…

12 results found.

“Let’s have lunch,” DK said in his email. “There’s something I need to talk to you about.”

Two days later, we were eating chopped chicken salads at City Oyster on Atlantic Avenue. We talked a bit about family news, but it was clear that he wanted to talk about a question that was on his mind.

The question: Should he spend $100,000 on the highest level of an internet marketing program that he had been looking at?

“It looks really good,” he said. “But I’m not sure it makes sense for me to invest that kind of money.”

“A hundred grand is a lot of money,” I said.

“But you get an awful lot for it,” he explained. “They do all the technical stuff for you, which I’m not very good at. All I have to do is come up with the product idea.”

The waitress filled our drinks.

“So if you invest in this marketing program… what kind of products would you sell?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” he said.

“How about this: If you had all the money you could ever need, how would you spend your time? What would you do to give your life purpose?”

“That’s a good question,” he said. “Actually, I like the idea of purposefulness. Maybe I’d do something along those lines.”

I told him that if I were he, I’d not spend a hundred grand on a program that gave me marketing and operational tools until I knew what I was going to do with them. READ MORE

I got this from Tim Ferriss’s blog. It’s a great word. (I posted an essay about this recently: “Are You an Information Addict?”)

Ferriss says: Japanese has wonderfully short words that can replace paragraphs in English. Sundoku is one such example.

Here’s part of the Wikipedia entry:

sundoku (積ん読) is acquiring reading materials but letting them pile up in one’s home without reading them. The term originated in the Meiji era (1868–1912) as Japanese slang. It combines elements of tsunde-oku (積んでおく, to pile things up ready for later and leave) and dokusho (読書, reading books). It is also used to refer to books ready for reading later when they are on a bookshelf. As currently written, the word combines the characters for “pile up” (積) and the character for “read” (読).

A Primer on US Inflation Rates

In his column on Monday, Sean talked about an important subject that I don’t know enough about: how the government handles inflation.

Let me start with this…

What I Do Know

I know that inflation, in simplest terms, is the phenomenon of currencies losing value over time. Thus, if one is speaking about the inflation rate of the US (or any other) economy, one usually speaks about the average increase of the costs of everything purchased in that economy over a given period of time.

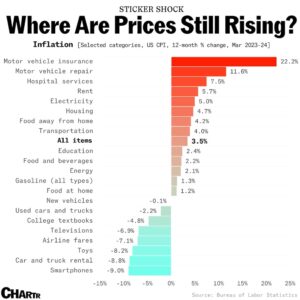

This is the chart that Sean presented on Monday:

It shows that the overall average inflation rate in the US from March 2023 to March 2024 was 3.5%. And as you can see, it is a number that is comprised of any number of inflation rates of different things bought and sold in the US economy. It includes motor vehicle insurance (which went up 22% in that 12-month period), housing (which increased by 4.7%), the cost of eating out (4%), energy (2.1%), and items like televisions, airline fares, and smartphones, all of whose prices decreased (deflated) during that same period.

In his commentary about the chart, Sean pointed out that a number of the items that had the highest inflation rates were related to the fact that in 2020/2021 there was a surge in Americans buying used (rather than new) cars, and this pushed the overall rate higher than it would have been otherwise. And since that trend was tied to specific events and not likely to last, he noted that there should be a correction in the cost of used-car-related expenses, and that the “deflation” in that market will likely result in lower overall inflation rates in 2024.

The Role of the Federal Reserve in All This

The Federal Reserve – the central bank of the United States – is a group made up of seven men appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Their primary job is to do their best to stabilize the US financial markets and keep them healthy – partly through regulations, but mostly by controlling the amount of money flowing through the economy. The main way they do that is by setting the rate at which banks and other financial institutions can borrow money from each other’s excess reserves overnight.

When the Fed’s rate is low, it is cheaper and more enticing for businesses and banks to borrow money. This supply of “cheap” money tends to stimulate the economy because lower interest rates make it more attractive for entrepreneurs to start new companies, for existing companies to increase the products and services they sell, and for the potential consumers of those products and services to buy more.

Stimulating the Economy by Lowering Interest Rates Is a Generally Good Idea, but…

There is a negative side effect of cheap money rates. And that is because of the relationship between the Federal Reserve (the Fed) and the US Treasury Department.

The Fed is just a group of presumably smart people sitting around a table, discussing dozens of factors and forces at play in the financial and business markets, and coming to agreement now and then about how much the government should charge for lending out its “money.”

The Fed has no money of its own. It is the US Treasury that has the money. But the Treasury doesn’t have all the money it needs to write checks for the tens of billions of dollars that the US government spends every year. It must cover the shortfalls by selling Treasury bonds and bills – i.e., government-backed promises to return the money it borrows with interest – to whoever is willing to buy them.

In the past, the primary customers of these promises (the primary buyers of US debt) were big, rich, profitable countries like Germany and Japan. Originally, the idea of this whole scheme was for it to be a temporary solution to a passing and pressing need – like the money needed to fight the Civil War. The idea was that this debt was going to be temporary. It would be repaid to the T-bond and T-bill holders with tax revenues. And to prevent the value of those dollars from being deflated over time, their value was officially tied to gold – gold that the government held in vaults around the country (like Fort Knox).

But that didn’t happen. The government found out that voters weren’t willing to have their taxes (and especially their income taxes) raised every time the government decided to go to war or fly a rocket to the moon or give aid to Haiti. The pols realized that if they wanted to get reelected to their cushy jobs, they had to promise to keep taxes down for the people and companies in their district.

So, that’s one big thing that happened. Despite the best hopes of those that created our taxing systems in order to fund their dreams of improving their world, there was from the get-go a growing gap between how much our legislators wanted to spend on their projects and how much gold-backed money the US Treasury had access to.

The battle between the conservative idea of spending no more than you have versus the liberal idea of borrowing money to pay for what you spend was lost – with the majority of politicians on both sides of the aisle realizing that if the Treasury Department could keep selling T-bonds and T-bills – i.e., if it could find governments and hedge funds to keep buying US debt – they could have their cake and eat it too.

There was, however, a limit to how many dollars they could lend out. And the limit was that each dollar was legally “tied to” the value of gold. By connecting dollars to the gold that the government had in its coffers, there was a limit to how large US debt could become.

This all changed in 1971, when President Nixon (supposedly a conservative) ended the convertibility of dollars to gold.Now, there was no natural limit to how many dollars the US could borrow. US debt was effectively unleashed from the anchor it had been tied to – the value of gold that the Treasury held – and that was the starting gun for a stampede of federal spending that brought US debt from $398 billion, when Nixon issued the directive, to nearly $35 trillion today!

Hold that thought while I get back to the Fed and inflation…

What happens in DC each year is that our legislators vote for a wide range of proposals, propositions, and projects to fund wars, build highways, help out single-parent families and homeless folks, fight drug addiction, bail out billion-dollar banks, and help victims of disasters in the US and all over the rest of world. And that makes them, and their constituents, feel like they are doing the right thing.

Of course, these projects, however needed or well-meaning, cost money. A gargantuan amount of money. Much more than our government has in its coffers. To pay for these programs we can’t afford, we call upon the services of the US Treasuryto bring in enough money to cover the shortfalls.

And this gets us back to inflation.

The Federal Reserve indirectly influences how much interest the Treasury can promise to pay on the T-bonds and T-bills it sells. If it raises those rates, there is less debt sold. When it lowers the rate, there are more buyers.

In essence, what the government is doing by lowering the Fed rate and thus increasing all of this borrowing of dollars that it (i.e., the Treasury) doesn’t have is increasing the amount of debt that the Treasury owes to its lenders (the T-bond and T-bill holders).

In other words, the lower the cost of borrowing dollars, the more IOUs the Treasury must print to satisfy the demand – and thus the more debt the US government will get into.

And getting into a lot of debt is never a good idea.

In 1950, when I born, the total US debt was $257 billion. In 1970, when I finished my sophomore year in college, it was $371 billion. In 2000, it was up to $5.67 trillion. And today, in 2024, it is over $34 trillion, making the US the most in-debt country in the world, more than twice as high as the world’s #2 debtor nation, China (at about $13 trillion). Click here.

How Economies Pay Down Debt

Now, I’m hardly an expert on economics. I’d call myself an interested amateur, at best. But from all the reading I’ve been doing about economics for the last 30 years, my belief is that there are only three ways an economy can pay down its debt:

1. By a miraculous surge of profitable economic innovation (very rare)

2. By a severe financial recession (like we had in 2001 and 1948 and 1930)

3. Or by a significant and sustained period of inflation.

The first option is extremely rare.

The next two are not just common but become probable once the national debt reaches a certain level. (By any realistic metrics, the US economy is already way past that.)

Back Again to the Fed

For the past 16 years, the Fed has been working hard to avoid either a financial collapse or a bout of hyperinflation by gradually easing and then tightening the money supply.

When Fed rates are low, banks and businesses are enticed to borrow more money to grow their revenues and profits. When Fed rates are high, the economy tends to slow down because fewer banks and businesses are borrowing money to invest in growing the economy.

So, on the one hand, when the economy is in a slump, the government wants the Fed to lower rates and thus boost spending. On the other hand, when borrowing is very strong, federal, corporate, and even individual debt grows, which makes for the likelihood of rising inflation.

Which gets us back to what Sean was saying in Monday’s column. He’s softly predicting that the Federal Reserve, assuming that there will be a natural decline in inflation due to the factors above, might decide to make one more reduction in the Fed lending rate before the end of the year. And if they do that, it should have a positive, stimulating effect on the economy – but not so much that it would greatly increase inflation.

And if that is true, there is reason to believe that, despite the way US debt keeps piling up, the US stock market (as well as some other US financial markets) may still have several months of growth ahead of them.

That’s what I know – and it’s a lot. But there are some questions about the government’s inflation numbers that I’ve never been able to find the answers to. So, I asked Sean to fill me in…

A Quick Q&A with Sean

Me: Sean, I am under the impression that the government inflation numbers do not include fuel and food. But they are a significant part of a middle-income family’s expenses. So how does one take account of that?

Sean’s Answer: This is… a nuanced issue. The government uses multiple models and measures of inflation to get an overall sense of price stability, which is their ultimate goal. CPI-U, CPI-W, Core CPI, PCE… the same way one looks at multiple KPIs in a marketing campaign to assess performance, the Fed looks at all of these (mainly PCE) to gauge inflation.

Core CPI does not include food and energy expenses – even though these are consumer staples – because they’re often traded speculatively in the market.

So, for example, you could have a drought, or a surge of futures buying, or a supply chain disruption cause the price of food to rise. But this rise in price doesn’t really reflect a decrease in the purchasing power of the dollar (which is what we’re really trying to assess).

Remember: Measuring the prices of things is a map, not necessarily the territory. Prices can fluctuate without it having anything to do with the stability or intrinsic value of a currency. (Which is a weird thing to say, considering that no money has intrinsic value – but I digress.)

Me: These numbers are reported every year as if they stand in historical isolation. If the inflation rate in one year is 8% and the next year it is 2%, the two-year inflation is 10%, right?

Sean’s Answer: It’s even worse than that. CPI inflation is based on an index – think a list of prices all tallied up and averaged.

If the CPI is 100 at year 0…

Then 108 in year 1… an 8% increase…

What’s 2% above that?

It’s not a CPI of 110 (10% cumulative). It’s 110.2. A 10.16% increase over two years.

Inflation compounds.

So, if we want to get back to a long-established 2% trendline, it’s possible that inflation needs to be under 2% for some time.

A recession could help with that.

Me: Isn’t it then misleading in a way to focus on the one-year rates? Take college tuition, for example. According to your chart, it was small or negative in the period measured. And yet tuition has probably gone up by a factor of 5 to 10 since I was in college. And the cost of a start-up home has gone up dramatically since I bought my first one in 1983. I paid $175,000 for a house that is probably $775,000 today.

Sean’s Answer: You’re absolutely right. And it goes even further than that. Because here’s the truth… ALL inflation data is misleading. The average person’s average experience is rarely ever “average.”

Everyone has their own inflation number. And that number is based on what they spend money on.

I had a conversation with an acquaintance about this the other day. He had been tracking his income and expenses for the last four years, and he showed me a model of the declining value of his income, which has been fixed.

But when I looked at his actual expenses… they were going down! He was spending less money on certain items and activities, but, to his chagrin, I pointed out that he was getting the same value/outcome as he did in 2020.

In other words, I explained to him that his personal inflation number was actually negative. His purchasing power has been going up.

The analyst Lyn Alden talks about this a lot. (She’s a genius.) She states that every household has its own personal Consumer Price Index.

To put it simply…

If you were a hermit who drove the same car since 1970 and only ever purchased women’s blouses and large-screen televisions… the purchasing power of your dollar has actually increased, not decreased.

That’s why, in my column, there’s a subtext of skepticism about headline inflation numbers and people’s perception of them.

Our understanding of inflation is about 100 years old. The notion that we should even strive for 2% inflation was invented by New Zealand on a whim in the late 1980s. We have a lot of different models of inflation because we don’t fully know what the best way to model inflation even is.

Me: Got it! Thanks, Sean!

What I Still Want to Know…

I came away from that conversation with a much better understanding of this very complicated subject.

Sean’s answers confirmed my belief that inflation is a serious matter and that if the Fed and Treasury make bad choices, inflation is, by definition, a way of lowering the buying power of every dollar and financial asset backed by dollars that I and my family partnership own.

He also helped me understand that some amount of inflation is inevitable and that – whether the number is 2% or some other number – the ultimate and perhaps only way to avoid economic disaster in the future cannot be achieved simply by raising and lowering the Fed’s lending rate, but by demanding that our legislators stop spending hundreds of billions of dollar each year that we don’t have.

Even after processing all of that information, though, I realized that I only half understand as much as I want to understand about inflation. And since I suspect that many of my readers don’t know much more than I do, I think I’m going to have to arrange another conversation with Sean for an upcoming issue.

Check out Sean’s YouTube channel here.

Diversity Quotas – Do Advocates Really Believe in Them?

Wokeness: the pathology of believing one can be virtuous by advocating ideas one hasn’t thought about.

Example…

Diversity quotas: the policy of establishing institutional quota systems for groups based on race, ethnicity, or gender.

In this short video clip, college students are asked if they agree with the policy of using racial quota systems to achieve “representative” diversity in colleges, businesses, and other institutions. Without exception, they agree. Then they are asked another question, which lays bare the superficiality of their thinking and makes at least a few of them think about the question for the first time.

Smart Choices, Martha Stewart, and Computer Logic

“Which car to buy?” “Which restaurant to eat at? “Which clothes to save and which to get rid of?”

“If I had a bit more time to research the alternatives and think about my choices, I could arrive at the best answer,” you might say. “Ain’t necessarily so,” according to Tom Griffiths, a computer logician.

In his TED Talk (below), Griffiths argues that many human problems – even mundane ones – are logically complex. Too complex to arrive at a “right” decision through research and hard thinking. To solve such problems, you must do what computers do, he says. And that means taking logical shortcuts.

One logical shortcut that works for quandaries like the three mentioned above is called the explore/exploit tradeoff. Griffiths explains it here…

By the way, recency of use, as Griffiths points out, is, in most cases, the most important criteria. I think it’s interesting that the two queens of domestic efficiency, Martha Stewart and Marie Kondo, include this as a key question.

Why Old Marketers Don’t Like New Ideas

“The strategies that made you successful in the past will, at some point, reach their limit. Don’t let your previous choices set your future ceiling. The willingness to try new ideas allows you to keep advancing.”– James Clear

One of the many counterintuitive things I’ve learned in my business career is that senior marketing executives – who should be eager to keep up with and test new advertising trends – tend to be among the most resistant to them.

I believe there are two reasons for this.

Thus, they are prone to dismissing new ideas as fool’s gold – superficially glittering but fundamentally flawed ideas that are unlikely to work because they don’t fit into their understanding of how things should work, which is based on their 20- and 30-year-old brilliant ideas.

In a recent blog post, James Clear discusses this. New ideas are often dismissed as gimmicks and toys, he says. “The first telephone could only carry voices a mile or two. The leading telco of the time, Western Union, passed on acquiring the phone because they didn’t see how it could possibly be useful to businesses and railroads – their primary customers.”

In our industry – information publishing – social media platforms are evolving at a rapid pace. I can’t keep up with them, but I hope our senior marketers will. Doing so will require them to resist their prejudices and keep an open mind.

A few of us were talking about how quickly information publishing is changing. When we got into it more than 40 years ago, everything was paper and postage stamps. The internet changed all that around the turn of the century. At that time, we paid attention and transitioned into digital publishing. The result was massive growth over the following 20 years, from $100 million to over a billion.

But today the landscape for digital publishing is very different than it was 20, or even 10, years ago. Social media is the name of the game and we’ve not been quick and able adaptors.

Speaking of Counterintuitive… Have You Heard of the Birthday Paradox?

There were 14 of us at the Cigar Club last Friday. I mentioned that I shared a birthday with one of them, Tony. I mentioned it because I thought it was unusual. Nanie didn’t think so. He said he’d read that any time you have 23 people assembled, there is a better than even chance that two of them will have the same birthday.

I rolled my eyes.

“It’s true,” Louis said. “It’s called the Birthday Paradox.”

I took a sip of my José Cuervo Reserva de la Familia. “Have you ever heard of the Cigar Club Paradox?” I said. “Whenever you have more than 12 people assembled, there is a good chance someone will try to bullshit you.”

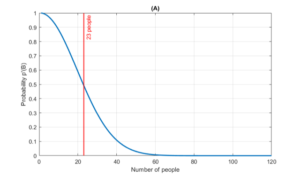

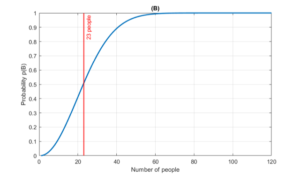

It turns out, the Birthday Paradox is a real thing. The next day, I received the following from both Nanie and Louis: two charts that prove it – and below that, a video that explains it. (Hint: It’s not really a paradox.)

(A) Probability of two people not sharing a birthday

(B) Probability of two people sharing a birthday

Click here to watch the video.

Kicking the Social Media Habit

TD, a friend and colleague, was heavily addicted to social media.

“It got to a point where I was checking my phone 100 times a day… and 95% of the time, I’m not using my phone for anything urgent or important. I just cycle through the same six or seven apps, checking for updates or messages. It’s a form of escapism from boredom and anxiety,” he said. “One consequence of this ‘checking’ compulsion is that I’ve wasted a lot of time hunched over a tiny screen for no reward.”

He implemented a 3-part solution:

He’s been at this for two months, but admits, “Frankly, I haven’t made a lot of progress.”

I became aware of the problem of email when I first began to use it regularly about 20 years ago. I was writing a daily blog back then called Early to Rise. Among other topics, I wrote about personal productivity.

“It’s becoming clear to me,” I wrote, “that email is going to be a major problem for me unless I get control of it. I find myself opening my email first thing in the morning and then spending several hours on it, but without much to show for it when I’m done. I think that’s because two-thirds of the nearly 100 emails I get each day are either (a) unrelated to my goals (and therefore distracting), (b) related to my goals, but trivial, or (c) messages from others asking me for favors.

“I don’t consider myself to be a morning person, but I’ve found I have the best focus and energy in the first three hours of the day. If I devote those precious hours to email, I’m not only wasting my best hours, I’m putting myself in the unfortunate position of having to do my important work when I’m tired and unfocused.”

The solution, which I recommended to my readers, was to do the important work first and save the email for later. “Break the habit of looking at your email first thing in the morning. Try to put off your email for as long as you possibly can.”

That one trick was a game-changer for me in terms of personal productivity. In the 21 years since I put that rule into practice, I’ve done all sorts of things I would never have done otherwise, including writing and publishing more than two dozen books, producing two movies, developing a non-profit community development center in Nicaragua, developing a 25-acre palm tree botanical garden in Florida, and a current project – building a museum of Central American art.

Social media wasn’t a distraction 20 years ago, but it is now. And to deal with it, I’ve added social media to my don’t-do-in-the-morning list.

After my important work is completed (which is usually in the mid-to-late afternoon, I open my email and sort it by urgency: (1) do today, (2) do this week, and (3) do this month. I do not respond to – in fact, I delete – anything I don’t have to do. Then I deal with my “do today” email, allowing myself no more than 2 hours. If I get it done in less than 2 hours, I work on some of my “do this week” email.

By the time I’m finished with email, it’s usually close to dinner time. I’ve done several hours of important work, and I’ve done all the less-important-but-still-necessary business work that comes via email. I have, in effect, finished working for the day. I am sometimes tempted to go on social media then, but I don’t. I go home and do my best to be sociable.

After dinner, I usually grab a cognac and cigar and sit outside. I spend an hour or on what I call “brain games” – i.e., the NYT crossword puzzle, Sudoku, and various quizzes, the sort of quizzes I sometimes pass along to you.

After that, I hit social media. I have a half-dozen “News & Views” sites that I go to first. I make notes and save some of them for future use. Then I move on to various “Entertainment” sites. These include odd and indefensible rabbit holes such as Karens in the Wild, The Professor (an amazing B-ball player), videos of bungling criminals, etc. A half-hour of this sort of low-brow fun is more than enough. Then I reward myself by reading a good book or watching a good movie.

I can’t say this system will work for everyone, but it works for me. It works for me because it is designed around my nature. I am not good at NOT doing things that I like to do, but I’m quite good at doing things that I think are good for me. By giving myself permission to partake in social media, I don’t feel like I’m depriving myself. But by doing a range of more important things first, I don’t have to worry that I’m wasting too much of my time on junk.

3 Words I’m Trying to Work Into My Conversations

* zaftig (Yiddish): Referring to a woman – having a full rounded figure; pleasingly plump; Example: “The actress playing the lead role was a zaftig blonde.”

* quinary: Of the fifth order of rank. Example: “She discusses other mixtures, including those of the secondary through quinary colors.”

* gigil: A Filipino word describing that sudden urge to pinch or squeeze an unbearably cute object or a person. Example: “The baby was so adorable I had the gigil to squeeze its cheeks.”

Worth Quoting: Obituaries

Obituary notices are not usually a source of great fun…

“If one should not speak ill of the recently dead, unless they were utter monsters such as Pol Pot,” said Theodore Dalrymple, writing in Taki’s Magazine, “one should not speak facetiously of them, either.”

The temptation is nevertheless great…

“You should never say anything bad about the dead, only good,” said Bette Davis upon learning of Joan Crawford’s death. “Joan Crawford is dead. Good.”

Clickbait (2021)

Available on Netflix

Created by Tony Ayres & Christian WhiteStarring Zoe Kazan, Betty Gabriel, and Adrian Grenier

There are so many good things – even great things – to watch on screen these days. But we all have a limited amount of time. With my schedule, I have about an hour or two a day to devote to TV and movies. So, I have to be selective about what I give that time to. Why not get the highest return for my investment?

That’s the theory. In practice, I am not infrequently seduced by what my mother used to call candy bar entertainment: Delicious. Addictive. Bad for your (mental) health.

You can’t always know from reviews or trailers whether the movie or series you decide to watch will be of the candy-bar kind. But what you can do is make it a rule to push the off button the moment you realize it is.

Last night, for example, based on something K had read, we decided to watch Macho, the new Clint Eastwood movie. It was awful right from the start. So it was easy to walk away from it after 15 minutes.

About a week ago, though, I decided to try Clickbait, a Netflix miniseries recommended by a friend. Unlike Macho, Clickbait was, from the beginning, engaging and entertaining. Binge-worthy. So I watched all eight episodes in three sittings, staying up two hours past my bedtime twice.

Was it worth it?

Plot: “Clickbait” is internet content that grabs you with an alluring promise but then fails to deliver. By naming this series Clickbait, Netflix was quite possibly promising the opposite.

The series follows the mysterious Nick Brewer (Adrian Grenier) as he struggles with his multiple roles as father, brother, son, and husband after appearing in an alarming video holding a sign indicating that once his taped confession of abuse gets 5 million views, he will die. Of course, the clip goes viral. Unsure where Nick is, his family must figure out how a man they only knew as caring found himself confessing to a secret life.

What I liked:

* Clickbait was, for sure, highly entertaining – in the sense of having a fast-moving and interesting plot that kept me wanting more.

* It was a whodunit. Sort of. But it was also an exploration of many elements of social media that are changing our culture.

* I liked the acting of two of the principals: Betty Gabriel (as Nick’s wife) and Andrea Elizabeth (who played Nick’s mother). I had mixed feelings about what Zoe Kazan brought to her role, but I thought many of the secondary roles, including those of Nick’s two boys (Cameron Engels and Jaylin Fletcher) were played well.

* I liked that it depicts an interracial family without making too much of it.

What I didn’t like:

* I found much of the plot to be annoyingly improbable. Everything from the romance between two of the lead characters, Pia (Zoe Kazan) and Roshan Amir (Phoenix Raei), to the scene where the villain is standing with his gun pointed at the cops and they aren’t shooting him.

* The tension and the surprises were done not through clever plotting but with fakes and feints. The plot itself was clickbait.

* Adrian Grenier, who was perfect in Entourage, didn’t bring enough to this role.

Roxana Hadadi, writing on the Roger Ebert website, said all of this better than I just did:

Clickbait is a reminder of why Netflix series became such hits in the first place. A cast of recognizable, serviceable actors dive with melodrama and zeal into a narrative that defies logical sense but moves at a breakneck pace, ends on cliffhangers like clockwork, and incorporates just enough zigs and zags to keep viewers guessing. The miniseries’ title is accurate enough: Clickbait grabs you, whizzes you along, and leaves you feeling satisfied before you forget everything you just watched. It’s not sophisticated, but it is highly bingeable, and its eight episodes are consistently outlandish enough to keep you watching.

Critical Reception:

* “Clickbait asks big questions and keeps you hooked…” (Karl Quinn, Sydney Morning Herald)

* “Alas, I finished Clickbait feeling had, as though – to use the title – I’d clicked on something that promised a bit of substance but delivered a whole lot of nothing.” (Matthew Gilbert, Boston Globe)

* “Obviously Clickbait has things to say about internet technology, misinformation, and the alarming, potentially dangerous speed of modern media. But mostly it’s just an elaborate whodunit.” (Tom Long, Detroit News)

You can watch the trailer here.

Book of the Week

The Wave: In Pursuit of the Rogues, Freaks, and Giants of the Ocean, by Susan Casey

I’m sure I would not have ordered this book had I not just finished watching “Octopus Teacher.” (See above.) I was deep in the beautiful mysteries of the oceans and didn’t want to come out of the water.

The Wave, I’d read, was a NYT bestseller. How could that be?

One reason, I discovered, was that Susan Casey is a very good writer. Another is that she writes about very exciting topics – in this case, giant waves. The 70- to 80-foot waves that extreme surfers like Laird Hamilton ride, but also the even bigger rogue waves and tsunamis that exceed 100 feet and can actually break an 800-foot ship in two like snapping a pencil.

The Wave is chock full of exciting stories about disappearing ships, as well as the history of giant waves, the new science behind them, and such fascinating miscellany as how Lloyd’s of London insures against them.

I’m only a third of the way into it, at this point, but I can already feel the excitement of the ride.

Click here to watch a talk that Casey gave about the book at a bookstore in California.

And click here to watch a TED Talk – “ Dispatches from the Dark Heart of the Ocean” – that she gave in Maui.

About the Author

Susan Casey, author of the NYT bestseller The Devil’s Teeth: A True Story of Obsession and Survival Among America’s Great White Sharks, is editor-in-chief of O, The Oprah Magazine. She is a National Magazine Award-winning journalist whose work has been featured in the Best American Science and Nature Writing, Best American Sports Writing, and Best American Magazine Writing anthologies. Her work has also appeared in Esquire, Sports Illustrated, Fortune, Outside, and National Geographic. Casey lives in New York City and Maui.

Reviews of The Wave

“Immensely powerful, beautiful, addictive, and, yes, incredibly thrilling…. Like a surfer who is happily hooked, the reader simply won’t be able to get enough of it.” – San Francisco Chronicle

“[An] adrenaline rush of a book…. As terrifying as it is awe inspiring.”

– People

“Casey’s descriptions of these monsters are as gripping in their own way as any mountaineering saga from the frozen peaks of Everest or K2.” – The Washington Post Book World

This essay and others are available for syndication.

Contact Us for more information.

“People who lie to themselves about investing are the same as overweight people who blame their genes for their obesity.” – Robert Kiyosaki

Lessons From “Losing a Million Dollars”

Growing up in a family of teachers and artists, I came into my adulthood knowing next to nothing about money. Curiously, that didn’t stop me from making a good deal of it. After a two-year stint teaching English Literature at the University of Chad for $50 a week, I began my “real” career in publishing. And during the next 10 years, I brought my income up from $35,000 a year to a whole lot more than that.

Figuring out how to make money happened pretty fast. After consciously deciding to “get rich” in 1983, I was in the top 1% of earners by 1985 or 1986.

But here’s the thing: I wasn’t getting richer. I think I may have even gotten poorer during those first several years. I went from having a net worth of maybe $30,000 to having a net worth of less than zero!

What happened is easy to explain: As my income went up, so too did my spending. Some of it was on depreciating assets – things like luxury cars and furniture and watches and jewelry. Some of it was on luxurious experiences – like first-class travel and expensive restaurants.

But most of it was on what I thought were “investments.”

Those quotes are to highlight a point. My ignorance of investing at that time was profound. Looking back at it now, I’d describe my idea of investing as “putting money into something that might make me richer somehow, some way, and some day.”

During those early years of investing that way, I had one or two memorable triumphs and dozens of disappointments. Which I promptly forgot. That was how I was able to get poorer while my income was soaring.

When you think of investing as something as nebulous as putting money into opportunities that might make you richer one day, you forgo the chance to understand the primary difference between investing and building wealth. So, let’s start with that – the difference between building wealth and investing.

Defining Our Terms

Building wealth is a good and sensible objective. Investing, on the other hand, is not an objective at all. It’s an activity. Something you do with your money. Just like exercising is something you do with your body.

If you want to build strength, there are many forms of exercise you can do to achieve that goal. Some work very well. Some are less effective. And some can actually weaken you. If your goal is to increase your wealth, you should likewise recognize that there are many activities you can engage in towards that objective. Some work very well. Some are less effective. And some can likely make you poorer.

In What I Learned Losing a Million Dollars, Jim Paul makes some very useful distinctions between 5 money-related activities that are sometimes lumped into the sobriquet of investing. This particular statement caught my eye:

“Most people who think they are investing are speculating. And most people who think they are speculating are gambling.”

That sounded like wisdom to me. I took notes. Here are Paul’s definitions:

Paul’s definitions are helpful because they identify not just the strategic and technical differences between these activities but also their different psychological motivations.

That is very important. Our mental/emotional approach to making money almost always drives our decisions. If we are unaware of our inner objectives and motivations, it’s easy to make bad decisions and then to keep repeating them.

Our investment psychology is complex. It includes our risk tolerance, our capacity for deferred gratification, our mathematical IQ, our willingness to learn, our attention to detail, and also such things as attention span, compulsiveness, and even our ego attachment to our decisions.

When you break it down like that, you can see why it is the principal factor in our ability to build wealth.

This was certainly true for Jim Paul. As he explains in the book, his early approach to making money on Wall Street wavered between gambling and betting. He thought of himself as an investor – even a brilliant investor, when the dice were rolling his way. But after losing a million dollars and nearly ruining his life, he figured out that what he was doing was anything but investing. What I Learned Losing a Million Dollars is a blueprint for how he reinvented his financial life.

Paul’s definitions are perfect for people who, like him, have an affinity for risk taking. The definitions below are my attempt to interpret them for people that have a relatively low tolerance for risk and for anyone that, like me, has little interest in investing but a great interest in building wealth.

Betting and Gambling

Paul makes an interesting distinction between the gambler and the bettor. The gambler, he says, is looking for entertainment, whereas the bettor is interested in proving himself right. If you are addicted to either gambling or betting, these distinctions are crucial. What is motivating you? Is it the fun of playing? Or is it the ego gratification of being right?

From a wealth-building perspective, however, gambling and betting are synonymous: foolish and habitual activities virtually designed to make you poorer. As a wealth builder, you should do neither of them. Ever.

Trading

Paul’s definition of trading is straightforward: making a market on (buying and selling) a particular asset over a specified amount of time.

The trader’s goal is to build his wealth one trade at a time by making a profit from the gap between bid and ask. His time frame is usually short, the risks are usually significant, and the trades themselves are sometimes complicated.

To succeed, the trader must be willing to spend a good deal of time on his trading. It’s not something one should do casually or impulsively. I see trading as an occupation like entrepreneurship, where you must work hours every day and keep up to date on your business. But it’s also a complex and sophisticated business, one that requires knowledge, intelligence, and discipline.

I’d like to think that I could be a successful trader. But on a deeper level, I know I don’t have the mentality to do it right. I don’t have the patience. I don’t have the discipline. And I’m not willing to put in the hours to learn what I’d have to know. Trading would definitely be a wealth-depleting activity for me.

My advice to anyone that wants to try his hand at trading: Be humble. Assess your mental and emotional qualifications. Move slowly. Never make a trade that you don’t fully understand. And don’t put money at risk that you are not prepared to lose.

Speculating

The speculator wants to build wealth by buying assets that he believes are either currently undervalued or will become more valuable. He makes his buy and sell decisions based on expectations of the future.

By that definition, most individual investors are speculators and most of what they do, which they think of as investing, is speculating. When you buy or sell stocks based on stories you hear about the economy, sectors of the economy, individual industries, and even individual companies, you are speculating.

There is nothing inherently wrong with speculating. Like trading, it is a perfectly legitimate way to build wealth. But there are smart ways to speculate and there are dumb ways to speculate. Wealth builders speculate smartly by doing what smart traders do. They learn as much as they can about what they are doing. They move carefully. And they limit their risks through a combination of diversification, position sizing, and stop-loss mechanisms.

Investing

Paul defines investing as parting with capital with the expectation of getting a return on it over a longish time horizon, with those returns coming from interest/income and capital appreciation.

The long-term time frame is key. It provides a level of safety that you cannot get with any of the other financial activities named above. To be a successful investor, you have to have or develop an aversion to risk and an ability to wait. But those are good qualities to have. They are, to me, the essential characteristics of a wealth-building mindset.

Paul’s definition of investing also mentions income and appreciation (or growth). These are worth parsing.

* Growth Investing – Growth investing is putting your money into an asset or business whose value you expect to increase over the long term. In other words, you hope to profit from some circumstances that will make the business or asset more valuable in the future.

* Income Investing – Income investing is putting your money into an asset or business for the purposes of generating income (or interest) from that activity. Lending money to someone or some business is a form of income investing. So is buying municipal or corporate bonds.

* Growth & Income Investing – This is my favorite type of wealth-building activity: putting money into a business or financial asset that will give me both current income and future appreciation. The best of both worlds.

Rental real estate is a perfect example. If I invest $100,000 or $1 million in a small apartment complex, I am usually looking for an annual return, cash on cash, of about 6% ($6000 or $60,000). Before buying the property, my partners and I do a lot of work to make sure that our net ROI will be 6%.

But I’m also counting on the growth of my equity – i.e., on property appreciation.

The historic ROI for real property is about 4%, which would bring my total ROI on that $1million to about $100,000 or 10%, cash on cash. This is just the beginning. The wonderful thing about the real estate market is that it’s both local and easy to understand.

Because I know my local real estate market, I know the value dynamics of the neighborhood in which I’m investing. In one part of town, I can bet I’d be lucky to get an annual appreciation of 3% or 4%. But in an up-an-coming area, I might expect to get 8% to 10%. And because real estate is relatively easy to understand, I can safely finance a portion of my investment and thus dramatically improve my long-term ROI.

You can get both current income and equity appreciation by investing in dividend-yielding stocks, too. Some of the best companies in the world are of this type.

The point is this: If you are interested in building wealth, you must understand that many of the financial activities that promote themselves as investing are actually forms of gambling and betting. You should also understand that to succeed as a trader, you must treat what you’re doing as a complex and risky business. And, finally, you should understand the differences between speculating and investing and the three types of investing.

Understand the activity. And understand your motivation.

You can tell yourself, for example, that when you buy crypto currencies you are investing. But if you analyze the strategy by using the definitions above, you will see that buying crypto currencies is a form of speculation.

Bitcoins are not businesses. Nor do they produce income. They are currencies whose values rise or fall depending on myriad future possibilities, not current facts. Buying bitcoin right now might be a smart speculation. It might even be a way to make a good deal of money. But because it is based on future possibilities rather than current facts, it is nevertheless a speculation.

Buying a bunch of gold bullion coins because you believe the world is on the verge of a debt-fueled economic crisis is not investing. It’s speculating. It is speculating because the decision is based primarily on the belief that the value of gold will go up in the future because of a variety of factors that are not possible to predict with any certainty. This does not mean that buying gold coins is a bad idea. In fact, it may very well be a good idea. But it is not investing according to the definition established above. It is speculation.

Putting your money in a tech stock that has huge revenues but no earnings may be a brilliant move. But it is not, according to the above definition, investing.

Again, I’m not saying that speculating is wrong. On the contrary, it’s a perfectly good way to build your wealth… if you do it right. But that means accepting the fact that you are making your decision based on future expectations, not current facts.

Alas, What Most People Do

Most “individual investors” buy and sell stocks and bonds based on information they have been told or read about, hoping that information will make them richer. The same is true for most people that buy gold and other precious metals. Their motivation is to profit from some imagined future event.

Most people that trade options do so because they have read about some systematic way to profit from options, without ever really understanding what they are doing. I myself traded options for a year or two – selling puts – and did about as well as I would have done putting my money in an index fund. At the end of the experiment, I had increased my wealth, so it met the test of being a wealth-building activity. But I don’t think the 10% return I got on my money would be enough to satisfy most people that trade options.

Today, almost everyone I know, young/old and rich/poor, is trading stocks. The new digital platforms have been designed to make trading incredibly simple and easy. What these people know about trading – or even the stocks they are trading – is next to nothing. But they think they know. What they are doing is not any form of wealth building. It is not investing. It’s not speculating. And although they call it trading, they are doing it with limited experience and even less knowledge. They are the equivalent of novice poker players playing with pros.

It might be argued that the above are arbitrary definitions. I cede that point. But I do think they are helpful in forcing us to pay attention to what we are actually doing when we put our money at risk. We need to understand the game we are playing – the costs, the benefits, the risks, and the potential rewards. We must also understand what sort of mentality we are bringing to these games.

We must take the time to ask ourselves: “What, exactly, am I doing?”

This essay and others are available for syndication.

Contact Us for more information.

“I’d like to think that anxiety is a form of emotional intelligence – alerting one to future threats that others ignore. The problem is it doesn’t work that way because anxiety is always forward facing. By the time tomorrow comes, you are worried about some new threat.” – Michael Masterson

11 Ways the COVID Lockdown Will Change the World, Good and Bad

Most breakthrough technologies make only a superficial difference, but Zoom is a game-changer. It has all the benefits of being in a room with others, with none of the drawbacks. Zoom meetings are, without question, more efficient. There is something about them that encourages people to spend less time chatting and stick more closely to the agenda. Plus, nobody has to waste time traveling – in some cases, for hours – to attend.

The lockdown has woken us up to the reality that most of our work can get done as well, or better, remotely. Even, as I said above, meetings. Office space is expensive. If you don’t need it, why pay for it? Two-thirds of our economy is now information-based. As a result of this trend, I’m guessing that businesses like those of my clients will graduate eventually to about 20% of the office space they currently use.

My partners and I just put a halt on a plan to raze the converted warehouse I work out of and replace it with a much larger, $14 million, glass and steel office building. We’ve always been big buyers of real estate. That’s over. We’ll be looking, instead, at selling ours. And we won’t be alone. According to Moody Analytics, the country’s office vacancy rate has been rising. So far, it’s gone from 9% in Q1 2020 to 15% in Q2.

The bulk of the office space that goes empty will be converted to apartments and condos. This will be a boon for construction companies that are able to efficiently do that sort of thing. But it will also put a pause on the new construction of apartments and condos for as many years as it takes to absorb the unused space.

All forms of information – from entertainment to news to advisory services – will convert their marketing models to subscription-based services. This change has been going on for some time, but it’s going to speed up. According to Zion Market Research, the subscription business model, valued at $3.8 billion in 2018, is expected to grow to $10.5 billion by 2025.

Despite claims that we can’t replace in-class learning, people are quickly discovering that remote education is perfectly well suited for at least 60% of the subject matter being taught today. Private colleges will realize, as other information businesses already have, that they can make more money and do a better job with computer-assisted programs.

Campuses will continue to exist for the social aspects of the college experience, but the amount of time kids spend in class will be slashed by 80%. Even more important – and this, I admit, is a wish rather than a prediction – students will opt out of such useless courses as gender theory and Marxist economics and spend their education dollars on courses they can profit from.

There is no longer any reason to travel to a mall, except for the enjoyment of having someplace to go. Strip malls will be the first to go. Half of those in existence are already dead in the water and won’t be coming back. Some larger, luxurious, shopping malls will thrive, but only a fraction of those that exist today.

Coresight Research predicts that 25% of all the malls in the US will close within five years. In February, Macy’s announced the closing of 125 stores over the next three years. JC Penny has plans to close as many as 150 stores. And, in fact, Simon Property Group (the largest owner of US malls) is working on a potential deal to turn closed department stores into Amazon fulfillment centers.

For most products, direct-to-consumer marketing will be the standard in selling. Online shopping and next-day delivery will become the norm. And even for products you might want to try on or try out – like clothes or tools or TV sets – increasingly easy return policies will bolster direct-to-consumer commerce.

All this remote (i.e., solo) shopping, entertainment, and education will cause an epidemic of anxiety, addiction, and depression – a serious problem that began surging as early as March.

Three examples:

* In March, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration’s “emotional distress” phone hotlines spiked 338%; their text hotlines skyrocketed from 1790 last April to 20,000 in April of this year.

* An analysis by the White House’s drug policy office reported an 11.4% year-over-year increase in fatal overdoses in the first four months of this year.

* An August poll taken by the CDC revealed that 25% of respondents aged 18-24 had considered suicide in the prior 30 days; 40% reported at least one adverse mental health condition as a result of the coronavirus.

Amazon’s current revenues are more than $300 billion a year, but the lockdown has given millions the opportunity to get used to online shopping. Amazon has big plans, and I don’t see how – other than by some kind of antitrust action – they can be stopped. I wouldn’t be surprised to see them bypass the $500 billion barrier in the next few years and go on to bypass Walmart.

What is a country but a political, economic, and cultural entity held together by a common mythology of identity and a touch of police and military power? Internet businesses like Google, Facebook, and YouTube have established their own cultures, economies, and politics that are funded by voluntary taxes and enforced by unilateral power over their hundreds of millions of digital citizens.

This essay and others are available for syndication.

Contact Us for more information.

Principles of Wealth #7*

To acquire wealth, it is helpful to know what it is… and what it is not.

There are many sorts of wealth. This essay is about only one of them: financial wealth.

Financial wealth can easily be defined as net worth – the sum of one’s assets less the sum of one’s liabilities.

You’d think a concept so simple and straightforward would be easy to understand. But surprisingly few people do.

Years ago, at an investment conference, I asked the audience to volunteer definitions of financial wealth. About a half-dozen were proffered, none of which was net worth. The two most popular were having a lot of valuable things and making a lot of money.

Neither one is true.

I bought a Richard Mille watch years ago in Paris. It was new to the market then, and I was in some kind of spendthrift mood. I bought it on impulse for $35,000.

A few years later, it stopped working. Getting it fixed cost me another several thousand dollars. A few years ago, it broke down again. That brought my total investment in the watch up to nearly 40 grand.

It’s a handsome watch, but it’s not any better looking than several other watches I’ve bought for a fraction of the price. And in terms of keeping time and reliability, it doesn’t compare to a digital Casio I could have bought at the time for $35.

I should be ashamed of myself for buying it in the first place. From a financial perspective, it was foolish. But I didn’t buy it to keep time. I bought it to give me a dose of serotonin – i.e., the thrill of spending money foolishly. And the purchase delivered that.

Since then, several people have complimented me on the watch. Those moments felt pretty good, too. And somehow, the combination of that first thrill and those half-dozen compliments feels like a fair deal to me.

On an ego-gratification basis, I feel like I got what I paid for. But from a net-worth perspective, I would have been better off buying a Casio and investing the rest in real estate.

When we acquire things for emotional reasons, we almost always pay more than they are intrinsically worth. And when we exchange our cash for status symbols, we generally make ourselves poorer in terms of net worth.

Acquiring status symbols is a bad way to build wealth. And having lots of expensive things is not a valid indication of wealth.

That kid driving the red Ferrari? The doctor with the ocean-front mansion? The woman wearing the Oscar de la Renta gown? The look says, “I’m wealthy.” But you can’t know that. The kid in the Ferrari might be making $40,000 a year. The lady in the gown could be in the middle of an expensive divorce. The doctor in the mansion might be worth less than nothing.

No, you can’t measure wealth by the things people have.

What making a huge income?

What about your idiot college friend that is “pulling down 200 Gs a year” selling life insurance? Or that jerk you met in law school that charges $700 an hour for his services?

Alas, that is no indication of wealth either. Earning a big income is certainly a very solid step in the right direction, but it is useful only if a good percentage of that income is saved.

What commonly happens when our income increases is that we reward ourselves by increasing our spending, too. The temptation to do this is almost impossible to resist for most people. And the serotonin hit we get from spending more becomes addictive. Before we know it, our spending has matched or exceeded all that extra income.

Once again, we end up poorer, not richer, despite the appearance – and even the feeling – of gaining wealth.

We cannot escape the simple truth of personal economics: Wealth is net worth, and net worth can only be grown by making more than we spend.

* In this series of essays, I’m trying to make a book about wealth building that is based on the discoveries and observations I’ve made over the years: What wealth is, what it’s not, how it can be acquired, and how it is usually lost.

This essay and others are available for syndication.

Contact Us for more information.

Part 2: Misunderstanding “Investing”

As a student of literature in college, I came into my adulthood knowing little to nothing about investing. That did not deter me from making money, but it did diminish my ability to convert that growing income into wealth.

As my income went up, so too did my spending. And of the spending I did, the most foolish were my “investments.”

I put quotes around that word to highlight a point: My ignorance of investing was profound. In fact, I could not even define the term. I might have attempted by saying something about putting money into stocks and bonds, but that sort of vagueness is not helpful. In fact, it is one reason most “investors” fail to grow their wealth faster than inflation.

When you think of investing as something as nebulous as putting money into stocks and bonds (or commodities or futures or real estate or gold mines), you lose the opportunity to examine the difference between different modalities of “investing” – such as trading, speculating, betting, and gambling.

And when you don’t make these distinctions, you can justify foolish behavior by giving it a name it doesn’t merit: i.e., investing.

Let’s start with this. There is a difference between accumulating wealth and investing.

Accumulating wealth is a good and sensible objective. But investing? It’s an activity – something you do with your money – to achieve the goal of accumulating wealth. Whether it can achieve that purpose depends heavily on what you are actually doing, which depends on your definition of investing.

Examples: my art collection, my botanical garden, my vintage cars, etc.

If you ask me to part with these treasured things, I will refuse. If you point out that they are “just sitting there,” costing me money (insurance/storage/maintenance), I will point out that their values have appreciated over the years and will likely continue to do so. In other words, they are investments.

I’ve been aware of the falseness of this posturing for many years. And I’ve written about it many times, pointing out that the problem with the word “investing” as generally used (especially by the financial industry) is that it puts a sort of seal of approval on a wide range of financial activities – from the cautious to the prudent to the speculative to the downright reckless.

So how do we distinguish? READ MORE