From The 7 Natural Laws of Wealth Building:

Gravity: The 6th Natural Law of Wealth Building

Why Most Investors Fail to Match Market Averages

In 1982, I got into the investment advice business by joining a start-up publisher in South Florida that specialized in B2B legal and business newsletters.

The founder – a former Wall Street broker and serial entrepreneur – soon decided to pivot into personal finance and investing. He asked me to lead the transition as CEO.

Over the next seven years, I helped grow that business from under $2 million in revenue to $135 million. We did it by serving a very specific group: mostly men, aged 55 to 75, recently retired or nearing retirement.

They weren’t satisfied with conservative returns. They wanted moonshots. Stock picks with 100% or even 500% potential. And they were willing to pay for any analyst who could make a compelling case.

We built an entire marketing machine around that appetite. Ads promising modest but realistic returns – say, 12% to 15% – barely moved the needle.

But ads that hinted at extraordinary ROIs (returns on investment)? They exploded.

At the time, I didn’t understand it. I couldn’t figure out why our subscribers were so obsessed with getting outsized returns.

After those seven years, I retired. I had amassed an eight-figure net worth and assumed I could coast on passive income from safe, stable investments.

I put two-thirds of my wealth into triple-A municipal bonds, with the rest in cash, gold, and a few blue-chip stocks.

I thought I was sitting pretty.

But that’s when I was brought back down to Earth.

A Note on the This Series of Essays

Over the last six months, I’ve been appropriating scientific concepts – principles that explain much about how the physical universe operates – and using them as metaphors for the equally complex, but no less universal, truths of building wealth. So far, I’ve covered Entropy, Inertia, Friction, and Momentum.

These aren’t literal laws. Rather, I am making creative comparisons to reveal underlying truths. Because when you set out to build wealth, you will face certain forces and resistances – just as you would in physics. And if you expect this, and you prepare for it, and learn how to work with or against it, you’ll have a much higher likelihood of success.

The natural law I am discussing today – Gravity – is the one I’ve taken the most liberty with. I’ve done so because I believe it illustrates a truth about wealth building that few people talk about – and even fewer understand.

Gravity: You Can Beat It Only Some of the Time

There is a force in physics that everyone intuitively knows and experiences every day. But while we can easily observe and model its effects, and we can describe it with incredible precision, we do not understand where this force comes from, or why.

It’s called gravity.

In physics, gravity is the force that holds things in place. It keeps planets in orbit, brings objects back to Earth, and defines the shape of motion.

In markets and business, there’s a kind of gravity that pulls things down, too. Not the kind that degrades and ruins things, like entropy, but one that draws outcomes back to their natural level. A reversion to the mean.

Every investment, every business strategy, has a natural rate of return. You might beat it for a while – maybe even for a long while. But the longer you stay above that baseline, the stronger the pull to return. Gravity doesn’t punish. It just balances.

You invest in an asset that outperforms expectations.

At first, the returns are exciting, even validating. But over time, the outperformance fades. Margins compress. The market adjusts. The returns start moving back toward their historical average. Nothing went wrong. It’s just the way things tend to go.

In business, it’s the same. You discover a strategy that works unusually well. For a stretch, it feels like you’ve found something truly different. But competitors learn, conditions shift, and the easy gains give way to steadier, more ordinary, results. The strategy is still good. It’s just no longer extraordinary.

The mistake is thinking that means failure. It doesn’t. It means systems have a center. They have a range that they tend to operate within, and when you drift too far from that center – up or down – forces begin to pull you back.

Recognizing that can make you a better investor, a better entrepreneur. It helps you spot unsustainable trends. It keeps you from chasing momentum too far or holding onto fading winners too long. And maybe more importantly, it teaches you to appreciate steady returns, consistency, and durability.

Understanding gravity means accepting that you don’t need to defy it to succeed. You just need to work with it. Let it shape your expectations. Let it temper your reactions. And when you do find yourself rising, know when to enjoy the view – without assuming you’ll float there forever.

Because in a world governed by gravity, staying grounded is often the smartest investment of all.

But that is not what I wanted to believe when I hit a net worth of $10 million by the age of 40.

My investment account was divided equally between stocks and bonds. The long-term ROI on stocks back then was about 9.5%, and I was getting about 4.5% on my bonds.

That gave me a combined average of 7%, which meant that the annual ROI I could expect in dollars would be about $420,000.

That’s a lot of income, even in today’s dollars. After income taxes, it left me with about $250,000. And that was further reduced by the expenses associated with keeping my house: mortgage payments, utility bills, the costs of upkeep and maintenance, etc.

Which left me with about $200,000.

And although an income of $200,000 is (and was) more than enough to live on comfortably, the lifestyle my family and I had adopted over the years – including luxury cars, lavish vacations, and private schooling for the children – amounted to a yearly outflow of nearly twice that amount.

Which meant I had three choices. I could…

1. Go back to work and somehow earn the cash needed to bridge the gap.

2. Aggressively reduce spending, which would probably have meant moving into a smaller house.

3. Increase the average ROI I was getting from my retirement account from 7% to 15%.

The Eternal Struggle: Trying to Boost the ROI

Fifteen percent didn’t seem crazy to me at the time. I figured I could safely increase my ROI by bringing up the percentage of stocks in my portfolio from 50% to 75%.

That was something. But the increase only improved my ROI from 7% to about 8.5%.

What else could I do?

I could replace my super-safe, triple-A rated, guaranteed municipal bonds when they matured with unsecured and lower-rated bonds that might get me another 1.5% yield, bringing the ROI on my bond portfolio from 4.5% to about 6%.

That brought the overall ROI I could expect to about 9.5%. The rest had to come from stocks.

At the time, my stock portfolio consisted of a handful of market-dominating companies like Coca Cola and IBM. To get higher ROIs, I traded about half of them in for a basket of growth stocks, which could conceivably bring my target ROI to about 12%.

From there, I had only one more tweak I could do to hit that 15% target: invest in speculative stocks whose risk profile was considerably higher but whose potential ROIs were those doubles and triples that some of the analysts I’d known in my previous career had been shooting for.

In doing all of this, I felt like I was acting wisely. I was in the unique position of being on personal terms with dozens of financial analysts, all with investment track records I could see. I wasn’t making blind decisions. I felt like I was acting rationally, not carefully. I was looking forward to learning more and making more, while watching the bottom line grow.

Of course, that’s not what happened.

What happened was that I slipped into a life that became increasingly about money – how much I had and how I should invest it to give me the best possible return. That didn’t feel like the retirement I was hoping for. It changed my life in seven not-so-great ways:

1. I was spending a lot of time looking at my stock and bond portfolios.

2. The more I looked at them, the more confusion I felt.

3. The more confusion I felt, the more questions I asked.

4. The more answers I got, the more second opinions I requested.

5. The more second opinions I received, the more contradictions in concept and in specific advice I got.

6. As these contradictions mounted, so did my feelings of anxiety and uncertainty.

7. The more I felt anxious and uncertain, the worse my decisions became – either acting impulsively and carelessly or freezing and failing to act at all.

I was experiencing the reality of what the investors that used to subscribe to our financial newsletters had experienced.

I was retired. I had no more active income. My lifestyle was entirely supported by passive income.

Legendary economist Paul Samuelson once said, “Investing should be more like watching paint dry or watching grass grow. If you want excitement, take $800 and go to Las Vegas.”

I knew that quote. I just wasn’t living it.

The Right ROI for the Right Role

ROI isn’t one-size-fits-all.

* Capital-dependent investors feel they need a high ROI because they’ve stopped earning.

* Entrepreneurs can rely more on active income and protect wealth with safer investments.

Chasing ROI without skill or discipline often reduces returns.

The real power move? Know whether you’re in a wealth-building or a wealth-preserving phase – and act accordingly.

My Escape Plan Back to Success

I don’t remember how long I swam in this swamp of financial self-delusion. It was more than a year, but less than two.

When you have the habit of checking your net worth every single month, as I had been doing since I “decided to get rich” in 1982, there are only so many times you can look at your retirement nest egg and see how many of those eggs keep disappearing every time you peek in.

I could no longer avoid reality. I had made a fundamental mistake about managing assets like stocks and bonds.

It is difficult to grow wealth by investing in financial instruments such as stocks, commodities, and options. Very few pros can beat the markets at all. And when they can, it is for a limited time before gravity kicks in.

Protecting the wealth that you have accumulated with passive financial instruments is considerably easier. It takes less knowledge, less attention, and less worry. And the results are much more reliable.

During the years when my money was in safe bonds and stocks, my portfolio grew at pretty much the market rates I expected: 9% to 10% for my stocks, 4% to 5% for my bonds.

That was, I realized, a wealth preservation strategy. And it was one that worked for me.

But when I changed my goal to actively increasing my wealth by taking more risk with stocks and bonds, my financial life became a nervous mess and my net worth was going steadily south.

If I wanted to maximize wealth, I needed to focus my time and energy on financial activities that had bigger potential on the upside than stocks and bonds, and risk profiles that could be significantly reduced by acquiring knowledge and regaining control of my finances.

I had to earn an active income.

And that’s exactly what I did.

How I Relaunched My Wealth

This realization, that I had to regain an active income, sparked the next major phase in my financial life – a 10-year period where I restructured my priorities and reallocated my time and resources towards a wealth-building plan that eschewed all the ideas and strategies that had failed me and replaced them with the ideas and strategies that had worked.

Always a fan of Pareto’s Principle, I devoted 80% of my attention, time, and resources to a combination of generating more active income and limiting unnecessary (or emotionally ungratifying) expenses.

That left me with 20% of my attention, time, and resources to focus on passive income – such as my retirement account.

The first and most obvious opportunity for creating more income was to deep-six my retirement fantasies and go back to work. But getting back into business wasn’t all I did. I also began saying “yes” to all sorts of financial opportunities that could generate income in proportion to how actively I took part in the day-to-day operations.

The best of these were in real estate. I began investing in income-producing (i.e., rent-generating) properties that I could not just own, but manage and develop too.

Thanks to a formula one of my brothers shared with me, I bought condos, single-family homes, and small apartment buildings that priced at no more than 100 times the monthly rents they could command.

This was, admittedly, a quick and crude way to value the properties. But it was also, I discovered, a very reliable way to make sure that I never greatly overpaid for any of them and that they always gave me a net-positive monthly cash flow.

I also invested in some small businesses – start-ups in financial publishing that were already producing an income. Which meant that, once again, I could base my investment in them on current income, rather than conjecture about their potential for growth.

So that was what I did that made a big difference in the rate at which my net worth grew.

I made another decision at the time that, in retrospect, was equally important: I decided to stop trying to beat the market with my passive investments.

This was big – so big that I should spend a bit of ink here trying to explain it.

Once my active, income-generating activities began to flow cash into my bank accounts every month, the time and effort I’d previously given to my passive investments all but disappeared. I mean, I was getting all this new cash coming in, and there was no reason to believe it would stop any time soon.

Moreover, the ROIs were significantly greater than what I was getting from the passive investing I was doing in stocks and bonds.

How did it make sense, I asked myself, to spend time stressing out on the hope of bringing my stock portfolio up to 20% a year, when shifting that money into an index fund would give me a long-term return of 10%, without risk of getting what other individual investors were getting – i.e., less than 5% a year?

Back to Gravity

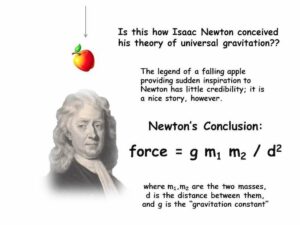

In the natural world, gravity determines so many things, from the arc at which the moon orbits the Earth, to the energy it takes to lift a plane off the tarmac, to the height a pole-vaulter can clear.

Going beyond these norms (i.e., defying gravity) is possible in the natural world. But it is difficult. It requires a considerable degree of additional energy input – often more than is rational to provide.

Likewise, in the world of wealth building, it’s possible to achieve more-than-average ROIs over short- and medium-term spans of time. But doing so requires an expenditure of intellectual energy toward finding a strategy that works and then researching and monitoring the individual investments made.

And that’s to say nothing of the amount of emotional energy it takes to stick to one’s strategy – even and especially when the investor’s feelings contradict his charts or signals.

And even if the investor is willing to put in all this extra time and energy doing the research and the monitoring, and even if he has the self-discipline to stay with his program despite his inclinations to do otherwise, history tells us that there is still no guarantee that he could beat the market – and especially beat it by a significant degree.

In fact, even professional investors – super-smart analysts that get paid enormous salaries and bonuses to manage stock portfolios for institutions or for individual investors – have a very tough time beating the markets. And when they do, it doesn’t last forever. Over the past 15 years, for example, less than 10% of active large-cap fund managers have outperformed the S&P 500.

Moreover, individual investors that try to mix and match advice from experts generally do considerably worse. On average, they see long-term ROIs that are a fraction of historical average ROIs.

Most ordinary wealth seekers don’t have the time, the willpower, or – to be frank – the emotional control to manage stock and bond investments successfully.

And many of them, despite the hubris of telling themselves they can, know in their hearts that they can’t.

So what they do is rely on professional investors to give them the buy and sell signals that determine the eventual ROI of their portfolios.

And although I was in the investment advice business for more than 40 years, and during that time worked with several extraordinary analysts that beat the market over time, I knew that many (perhaps most) of their readers and clients did not have the mental and emotional discipline to adhere to the strategies they had created.

Once I recognized what had happened with my own stock, bond, and cash-equivalency investing – i.e., that despite having direct access to some of the best analysts in the world I was still failing to achieve even historical averages for stocks, bonds and cash – I began to see the historic ROIs as almost insurmountable forces of financial gravity.

However, as mentioned above, there was one thing I was doing that was giving me ROIs that were greater than 10%: investing in start-ups and young businesses that (a) I understood from the inside-out and (b) could generate income from day one.

I recognized that an essential component of my success with these businesses was the result of being an active participant in them. I not only understood them well (because I worked in them), but because I was a direct investor, I had some degree of authority when it came to key product development, marketing, and sales decisions.

That changed my strategy for accumulating wealth.

From then on, I told myself, I would desist from trying to beat the markets when it came to stocks, bonds, and cash. I would learn to be happy with historic averages for each. I would put my energy towards the active, income-oriented businesses I understood and over which I had some control – which would give me the greatest chance of getting big overall ROIs, without taking on all sorts of risks that come with an attempt to defy gravity.

And that is what I tell people who ask me for advice: Put your stock, bond, and cash investments in funds designed to equal, not exceed, historical averages. Then look for higher ROIs by investing in businesses that you understand and can, to some degree, control.

Sources

* Historical Stock Market Returns: The long-term average annual return for the S&P 500, including dividends, has been approximately 9.5% since its inception in 1926. Source: Morningstar, Ibbotson SBBI Yearbook.

* Bond Market Averages: US government and AAA-rated municipal bonds have historically returned between 4% and 5% annually. Source: US Federal Reserve historical data; Vanguard bond fund returns.

* Performance of Active Fund Managers: Over a 15-year period, 88% of active large-cap fund managers underperformed the S&P 500. Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices, SPIVA US Scorecard 2023.

* Paul Samuelson Quote: “Investing should be more like watching paint dry or watching grass grow. If you want excitement, take $800 and go to Las Vegas.” Source: Quoted in The Money Masters by John Train (1980).

* Pareto Principle (80/20 Rule): This principle is commonly applied in business and personal finance to emphasize high-leverage actions. Source: Richard Koch, The 80/20 Principle (1997).

* Investor Behavior and ROI: Studies by DALBAR and Morningstar have shown that individual investors underperform the market primarily due to poor timing decisions, emotional trading, and inconsistent strategy adherence. Source: DALBAR’s Annual Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior (QAIB), 2022.