My Report Card on Trump’s First 30 Days

President Donald Trump has completed the first month of his second term in the Oval Office. In those four weeks, he has signed 73 executive orders, including 26 on his first day. That is more than any president has signed in their first 100 days. And that’s not counting the 23 proclamations and 12 memorandums he issued.

The response from Democrats and the Legacy Media has been nothing short of hysterical. All the tropes repeated so desperately as the election neared – the end of Democracy, the imminence of fascism – are being frantically repeated, creating a severe sense of anxiety among those who were certain Trump could never be re-elected.

However, the recent anti-Trump protests have not been well-attended, and the proclamations from TV anchors and Hollywood celebrities have reached an ever-decreasing watcher/listener base, as millions of subscribers to the Legacy Media have abandoned it for what Musk calls the “new media – i.e., internet influencers, some of whom have individually much greater viewership than the Legacy Media does as a whole.

That said, one cannot deny the impact Trump’s executive orders have had on American political discourse and that of the entire world. And for good reason. Although the total number he’s signed and may sign over the next four years is going to be substantial, it doesn’t look like he will smash any records.

|

Executive orders have been a common tool for US presidents for all my adult life. Richard Nixon signed 346 of them for an average of 62 each year. Gerald Ford signed 169 for an average of 69, followed by Jimmy Carter, who signed an astonishing 320 in one term, averaging an all-time high of 80 per year.

Ronald Reagan signed 381 during his two terms, averaging 48 per year, followed by George H. W. Bush at 166 with a low of 42 a year. Bill Clinton signed 364, averaging 46 each year, followed by George W. Bush at 291, for just 36 a year.

Barack Obama signed 276 over his two terms, averaging a bit less at 35 a year. Trump signed 220 in his first term in office, a yearly average of 55. And Biden signed 162, for a yearly average of 41.

It’s clear (to me, at least) that this deluge of executive mandates that Trump has issued so far was a predetermined strategy to take full advantage of the fact that he won the popular vote and, more importantly, secured the Republican majority in both the House and the Senate in order to accomplish as many of his campaign promises as can be achieved before the 2028 midterm elections.

What’s not so clear is whether he will continue at this pace throughout the next four years.

Most Republicans and conservative voters are more than pleased with what he’s been able to do already. Yet there are still tens of millions of Americans who are not at all happy. In a recent poll by Market University (which traditionally skews to the left), approximately 40% of all voters are worried that he is on a path that will lead to all sorts of changes in government that they believe will be bad for them and possibly even for the nation as a whole.

Since 2016, Democratic politicians have united in opposition to everything Trump wants to do, as evidenced by the nearly unanimous opposition of Democrats to every single one of his departmental nominations. (This is not what happened with Biden’s nominees.)

The Legacy Media is also alarmed and upset, with CNN, MSNBC, the NYT, the WP, and the Associated Press publishing negative stories and editorials about Trump’s initiatives every single day.

(If Trump still likes seeing his name in print as much as he used to, he must be very happy with what’s going on now. I did a quick scan of one day’s worth of online news from the Legacy Media and found that more than 70% of it featured “Trump” in the headlines.)

What About the Voters?

I’d characterize the feelings of those that voted for Trump in 2016 as ranging from relieved to optimistic to overjoyed. In contrast, the feeling I get from those that voted against him twice – the Never-Trumpers – ranges from disappointed and fearful to outraged.

I know a few people who voted against Trump in 2016 but then voted for him in 2024. I’d characterize their feelings as uncomfortable.

Within my circle of friends and family members, the reaction has been in line with the opinions they have held about Trump for the last eight years. From what I’ve heard and seen of their conversations, their conviction that Trump is a wannabe dictator, and that America is doomed is very much intact. But since the election, the direction of their animus has widened. It now includes virtually all his cabinet appointees, whom they are labeling as racist, transphobic fascists unqualified for their jobs. Elon Musk is, of course, the worst of them. In their view, he’s a wannabe Hitler who has no idea what he’s doing.

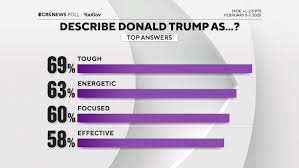

Those are observations from my personal sphere of reference. They are not necessarily reflective of the US voting population overall. If you’ve been looking at the national polling on Trump in the last several weeks, you’ve seen that his overall approval rating is up about 5%, and up about twice that on the major issues he campaigned on (energy policy, DEI hiring, gender theory, and the handling of the Russia-Ukraine and Israeli-Palestine wars).

Why would that be?

It’s certainly not because of any favorable treatment Trump has been given by the mainstream media. At best, there is the occasional recognition of how the polls have moved in his favor – but 99% of the coverage of his actions has been negative.

In fact, I’ve been amazed at the creativity of some of the anchorpeople and pundits in explaining how every executive order that Trump has signed is bad news. And they are still using the same slanderous tropes in characterizing them – racist, sexist, homophobic, transphobic, illegal, unconstitutional, and a threat to Democracy. Don’t they realize that all those efforts to cancel Trump into oblivion were the very things that gave him the victory he enjoyed?

How is it possible to argue that it’s wrong to get rid of government waste and corruption?

Or that America should not be doing everything it can to end those two immensely savage and destructive wars?

Or that it is reasonable to prohibit children from smoking or getting permanent tattoos while they are still children, but they should be allowed to take life-altering drugs or have their body parts amputated?

I can think of only one reason why Trump’s approval ratings – both for himself and his executive orders – are so strong. It must be that, despite what they said in public, there were millions of Americans who voted for Harris that were disappointed in her nomination and felt that, despite his shortcomings, Trump had the better ideas. And now that he is putting those ideas into action, they are quietly relieved.

What did Trump promise to do?

Throughout 2024, Trump was not shy about criticizing the things he believed Biden and his appointees did wrong. Nor was he abstemious in making promises about what he’d do if he were elected president.

I did a little search on the campaign promises he made most often, and this is what I found (including some of his specific phrasing when I thought it might be helpful). He said he would:

* Head up the “largest deportation of illegal immigrants in American history.”

* Bring a “quick end” to the Russia-Ukraine and Israeli-Palestine wars, both of which “broke out during the Biden administration because of Biden’s policies.” He also stated that the peace he would bring would be “one that would last.”

* Conduct a massive audit of all government spending, from every branch of government, for the purpose of uncovering “waste, fraud, and abuse.”

* “Put an immediate end” to federal government support of DEI, BLM, and other “America-last” programs and policies.

* “Root out corruption” in the FBI and the Department of Justice, which had taken part in the Russian collusion hoax that nearly overturned his presidency.

* “Bring free speech back to America” by ending the “collusion” between government agencies and big media, including social media, and by “hunting down” and prosecuting those that were illegally involved in such crimes.

* Ban “sex affirming care” for children.

* Make public a trove of currently classified documents that either should never have been classified in the first place or have no more reason to be classified, including documents about the assassinations of JFK, RFK, and MLK.

* Impose tariffs on China, Panama, Canada, and other countries whose trade balances with the US “favored them and not America.”

* Use tariffs to get cooperation from Mexico and Canada on the border crisis, and to put pressure on US and foreign companies to locate their headquarters in the US.

* Pull the US out of various international agencies, such as the World Health Organization, that have “worked against the interests of the United States.”

* Launch a Department of Government Efficiency, headed by Elon Musk, to reduce the size of government by exposing and eliminating corruption, abuse, and inefficiencies in every sector.

So how many of those promises has he kept?

I’ve compiled a list of the executive orders Trump signed in his first 30 days that address the oft-repeated promises listed above. Note: They were compiled from several sources, but they are all linked to their entries into the Congressional Record so you can read them in detail.

* Restoring freedom of speech and ending federal censorship

* Ending radical and wasteful government DEI programs and preferencing

* Withdrawing the United States from the World Health Organization

* Ending the weaponization of the federal government

* Restoring the death penalty and protecting public safety

* Defending women from gender ideology extremism and

* Ending illegal discrimination and restoring merit-based opportunity

* Declassification of records concerning the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy, Senator Robert F. Kennedy, and the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

* Emergency measures to provide water resources in California and improve disaster response in certain areas

* Enforcing the Hyde Amendment

* Reinstating service members discharged under the military’s COVID-19 vaccination mandate

* Protecting children from chemical and surgical mutilation

* Ending radical indoctrination in K-12 schooling

* Expanding educational freedom and opportunity for families

* Withdrawing the United States from and ending funding to certain United Nations organizations and reviewing United States support to all international organizations

* Keeping men out of women’s sports

* Eradicating anti-Christian bias

* Establishment of the White House Faith Office

* Eliminating the Federal Executive Institute

* Ending procurement and forced use of paper straws

* Implementing the President’s “Department of Government Efficiency” workforce optimization initiative

* Protecting the meaning and value of American citizenship

* Keeping education accessible and ending COVID-19 vaccine mandates in schools

How do I feel? What do I think?

I am among those who feel optimistic about the overall effect of Trump’s executive orders, with one reservation.

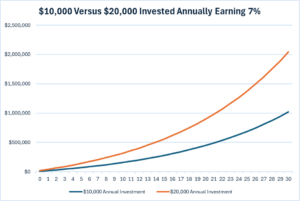

Let’s start with this: Most Americans, including college-educated Americans, have zero understanding of economics. They know nothing about trade deficits or balanced budgets or federal debt. Thus, they are blind to the elephant in the room: that the US is the most in-debt nation in the history of the world with $36 trillion of federal debt (that’s a $200,000 burden on every living American) plus trillions more in state, local, corporate, and private debt, totaling close to $100 trillion!

They don’t realize that our economy is on the brink of a massive collapse. A collapse much larger than the Great Recession of 2008. A Great Depression collapse. When you understand the numbers, it’s impossible not to see how true this is.

There are only two ways an economy can survive the level of debt the US is in right now. One way is for virtually all Americans – rich, middle class, and working class – to get a lot poorer, either by sustained inflation or by a huge economic depression. The other way – less likely but still a possibility – is by a sudden and sustained growth in the GDP at such a rate that the government (and its taxpayers) can use the extra wealth to pay off debts and return to a balanced budget.

This better scenario – a surge in GDP growth and thus tax revenues sufficient to pay down the debt – cannot be done without an equally great surge in energy production. (Energy is and always has been the fuel of economic growth.) Which would mean that Trump would have to convince Congress and the American voters that drill-baby-drill is a good idea. That won’t be easy.

And it won’t be enough. The Trump administration and Republican lawmakers must also put the brakes on government spending. Spending for social services. Spending for war. And spending for a thousand boondoggles that favor individual legislators from both sides of the aisle.

I want to believe that can happen. But I’m not holding my breath.

I feel desperately hopeful about the work Trump is doing on the Russia-Ukraine and Israeli-Palestine wars.

I’ve always believed he was right when he said that neither of these terrible wars would have started had he been president from 2022 to 2024. And if he isn’t blocked from doing what he wants to do, he will succeed.

But he is already encountering strong opposition from Liberals and Conservatives and from the media. I was not surprised that the left-wing media has been promoting these wars. Nor does it shock me to see Liz Cheney and other neocon Republicans voting for it.

I am disappointed to see The Wall Street Journal and many other so-called conservative publications and news shows frantically criticizing Trump for intervening to end those wars. Not just end them but negotiate a deal with China and Russia to cut our mutually insanely expensive defense spending in half. How can that be a bad thing? (Unless you believe the same tropes about Communism that got us into the Vietnam War?)

How did it happen that my generation of Americans, the Baby Boomers, went from mistrusting government and denouncing war in our teens and 20s to advocating government censorship and war 50 years later?

I feel worried but hopeful about the immigration “crisis.”

During the four years Biden was sitting in the White House, he, his cabinet, and the Democratic Congress executed a slew of laws, regulations, executive orders, and proclamations that allowed about 10 million migrants to cross the Mexican and Canadian borders. (About 60% to 70% of them have not been turned back.)

Since Trump took office, that torrent has slowed to a trickle, with average daily “encounters” of illegal immigrants being cut to a de minimus 500 or 600.

On a yearly basis, that means there are at least five million fewer migrants entering the country illegally now than there were in 2020. It has been costing us somewhere between $150 billion and $400 billion to support those that were able to settle in the States. Knocking that bill down by 80% is inarguably a good thing.

But not all migrants that settle in the US are on government handouts. Most of them are working hard, spending money, and sometimes even paying income tax. Losing that productivity and those taxes is inarguably an economic negative. That is, assuming that they are not, as some argue, putting an equal number of American citizens on government aid.

There is no doubt that the US economy needs some number of low-skilled and low-paid migrant workers. The question is: How many?

This is not an unanswerable question. The data is available. And it doesn’t take an advanced degree in math to figure it out. What we need is what both Republicans and Democrats have been calling for all along: a sensible immigration policy that is net positive for our future GDP.

We could do it. But it can’t happen so long as immigration is a political issue. I don’t think we ever could have done it with millions more people coming into our country than our economy needs. As I said, the data is easy to access. The numbers are easy to find. And the arithmetic is simple. What we are missing is the willingness of legislators on both sides of the aisle to stop using the “immigration problem” to win votes – to just get together and do the math.

I have mixed feelings about Trump’s initiatives on tariffs.

As a student of Milton Friedman, I’ve long viewed tariffs as economically self-destructive. Used as a strategy to protect one industry or one group of products, tariffs will inevitably increase the average price of all products for everyone.

I still believe that in principle. But I can’t say I am not attracted to the argument that until the income tax was instituted in1913 (not counting a brief experiment with it during the Civil War), American citizens were able to enjoy the benefits of government (primarily protecting life, liberty, and freedom) without having to pay a dollar in income tax.

It was, of course, possible back then because our government was a fraction of the size it is now. The current cost of our federal government is about $4 trillion a year and growing. Our imports cost about the same. (I think I have that right. The numbers are tricky.) Even if DOGE was able to reduce government spending by half and we were able to tax all imports to the degree Trump has suggested, it would not come close to paying for all that our politicians, with our blessing, keep spending each year.

So, I’m doubtful about that.

That said, Trump has another reason for threatening tariffs. He’s a deal guy, and he has been using the threat of tariffs to achieve geopolitical goals. Most of which most Americans agree with. (Such as securing our border against unsustainable illegal immigration and drugs and criminal cartels.)

What he’s done so far by threatening to impose tariffs on Mexico and Canada has been nothing short of amazing. He’s persuaded them both to begin to police their borders and prevent the free passage of undocumented immigrants through their countries into ours.

And by the way. As I’m writing this, I see that Trump’s threats to impose tariffs on all goods coming from China has prompted Apple to announce that the company is relocating its headquarters to the US, which represents a $500 million investment in America and the creation of an additional 20,000 jobs.

I’m also hopeful about Trump’s promises to reduce taxes.

Despite what Democrats can’t stop themselves from saying, it’s not possible to stimulate an economy by taxing the rich. Every country that has tried this has failed. The unpretty truth is that the only way to stimulate growth through taxes is to lower them on the rich.

When a government lowers corporate income tax and other taxes on big companies, the lion’s share of the money saved goes into growing more business, which means growing employment and increasing the income of workers. And all that money is taxed. The same is true when taxes are lowered on the wealthy. Unless they bury the money that they save from lower taxes, it flows into the economy in terms of investing, which grows the GDP.

Trump understands this, but most voters don’t. And that’s why, despite the success of the tax cuts we’ve had in my lifetime, it’s still difficult to get trickle-down economics to work.

I am doubtful but still hopeful that Trump can grow our economy.

If he manages to lower taxes on the rich, and uses tariffs sensibly, we could see an amazing renaissance of the American economy. We could see growth in the energy sector, growth in the high-tech sector, growth in Berkshire Hathaway companies, and growth in the financial sectors as well.

If Trump and his appointees can somehow convince their political opponents to cooperate, I believe it is absolutely possible to get the US economy growing again. And if that happens, so many other things that are troubling Americans – including weak employment metrics, stagnation in personal income, inflation in goods and services, a lack of affordable housing, and even many social ills (such as crime and even our pandemic of clinical depression and suicide) – can be reversed.

I’m not holding my breath, but I’ve got my fingers crossed.

I am 90% optimistic about all the Woke social issues.

This is an area that frightens many people, particularly the gay population who have reason to be worried about all the old prejudices and even laws and regulations that minimalized and even criminalized homosexuality in America. And I believe there are some people of color that are worried about the same thing – that fear the ending of government support for DEI may trigger a regression back to Jim Crow days.

I don’t think these fears will be realized. But I won’t say it’s not possible. When the political or ideological pendulum swings too far in one direction, there is a possibility that it will return too far in the opposite direction.

I believe that the most important factor in Trump’s victory was not the economy or the wars or even immigration. I believe what did Biden and Harris in (and so many of their party), was the promotion of identity politics, including the BLM movement, concepts such as systemic racism and cultural appropriation, but most importantly the insane idea of trying to create a legal system where supposedly free citizens had to pretend that men can have babies and should be able to use women’s locker rooms and compete in women’s sports.

The reason I believe that was the key issue is the same reason that nobody is willing to say it was the key issue: It’s such an obviously fake idea that everyone, including those that promoted it and those that fought it, knew that it defied common sense.

Fundamentalists – Christians, Jews, Muslims – found the whole four years of it to be unbearable. Not frightening, but disgusting, retrogressive, and stupid. Conservatives found those years to be incomprehensible. They shook their heads and hoped identity politics would magically disappear. Libertarians, such as yours truly, believed that adults had the right to dress however they liked and refer to themselves however they wanted, but they had no right to impose their fantasies on others.

There were only two groups that advocated for trans ideology: ex- or avant-garde college professors that made a modest living indoctrinating students into post-modern nonsense, and identity hustlers – politicians, pundits, and public intellectuals who made sometimes very good money promoting the idiotic nonsense taught at the universities to left-leaning voters who believed that repeating these ideas would demonstrate how smart and virtuous they were.

I am hopeful that the pendulum will return to a middle position – one which grants to everyone, including those who believe they were born in the wrong body, the same human rights. They should be able to live without fear of being assaulted or discriminated against. But they must recognize that what our Constitution gives them is protection from bodily assault and slander, not from microaggressions that may make them feel bad.

I am hopeful about the possibility of making America healthy again.

The US spends more money (absolutely and on a per capita basis) on health and medicine than any other country on Earth. And yet in every health metric that matters, we are not even in the top ten. We are a fat, lazy, and sickly population destined to spend our after-30 years suffering from avoidable chronic diseases and then die at least 10 years before we should.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. understands that. I’ve been following him (including reading his books and essays) for decades – probably since I got into the natural health publishing industry in the late 1980s. As head of the Department of Health and Human Services Department, he has a big job ahead of him. I’m not going to take up any more of your time right now trying to convince you that he is (and was) the right man for that job – but I will be devoting an essay on that in the near future.