Stoic Paradoxes by Cicero

A New Translation by Quintus Curtius

106 pages

Paperback published 2015

I’ve done what I’d consider the basic requirements of Stoic studies since it became the predominant philosophic perspective of the self-help bloggers about 20 years ago.

I’ve read Marcus Aurelius, Seneca, and bits of Zeno, Epictetus, and Diogenes. But I’d never read Cicero.

I decided to read Paradoxa Stoicorum (Stoic Paradoxes) – written by Cicero sometime in 46 BCE – after reading somewhere that in it “he attempts to explain six famous Stoic sayings that appear to go against common understanding.”

I’ve always had a weak spot for concepts that are contra-intuitive. I like to learn them and then use them as burrs to irritate the minds of those who are confident in their thinking.

There are, admittedly, other explanations. Your average second-year student of psychology would probably (and correctly) diagnose me as (a) rating high on the “disagreeable” scale, and (b) having recurring “narcissistic” tendencies.

Never mind. The point is that I’m glad I read this. Not only is it intellectually challenging, I have gotten a few nuggets from it that will help me sound like I know what I’m talking about in future conversations about Stoicism.

The Six Paradoxes

I’m certainly not an expert in Stoicism. However, I feel confident in saying that it is an ethical philosophy that advocates for the development of character based on reason.

In Paradoxa Stoicorum, Cicero examines these six principles of Stoic thought:

1. Virtue is the sole good.

By this (I think) Cicero is saying that there are some goods (things like pleasure and fortune) that, however satisfying for the moment, cannot give us enduring satisfaction. They merely arouse the desire for more of the same. The goods that can satisfy the soul, he says, are honor, honesty, and virtue. And these can be attained only by disassociating oneself from impulses and desires and committing to the fruits of reason.

2. Virtue is the sole requisite for happiness.

Virtue is all that is needed for happiness. Happiness depends on a possession which cannot be lost, and this only applies to things within our control.

3. All good deeds are equally virtuous and all bad deeds equally vicious.

This one I had problems with. Apparently, the classical Stoic idea is that all vices are equal because they each involve the same decision: to break a moral law. Cicero’s argument seems to be that all vices are the same but only if they are equal in terms of the social statuses of the offender and the offended. A person of lower status offending a person of higher status deserves a considerably harsher punishment than a person of higher status offending a person of lower status.

4. All fools are mad.

This one I didn’t get. Or if I did, it is a specious argument. Cicero seems to be saying that people that are not virtuous are, by definition, mad because any sane person, understanding that the only good is virtue, would act virtuously and therefore be immune to punishment or failure, whereas any person that chooses to be unvirtuous, is, by definition, a fool.

5. Only the wise are free, whereas all fools are enslaved.

Here, Cicero seems to be making the same argument (that all fools are mad) in a different way. Virtuous people are free because they are making choices based on reason, whereas people that act in accordance with their desires are always locked into the tyranny of those desires.

6. Only the wise are rich.

Again, this seems to be a variant of the previous three. On the one hand, since virtue is the only good, seeking other goods – such as fortune, fame, and power – will never produce any lasting good. On the other hand, someone who has an abundance of fortune, fame, and power cannot be said to be rich if he has no virtue.

What I Liked About It

* I believe the subject matter of Stoicism is important because it deals with two of the most important philosophical questions: What is a good and rewarding life? And how does one attain it?

* By finally reading this book, I feel that I now have an understanding (at least a partial and introductory understanding) of Cicero’s contribution to Stoic thinking.

What I Didn’t Like So Much

* Although I now have something to say about Cicero, I don’t have a deeper or even a much broader understanding of the range of Stoic thinking.

* Since the book is a translation of a translation (Cicero translated the Stoic arguments from the Greek), it was pretty much impossible to get a sense of how close the ideas were to the original.

About the Author

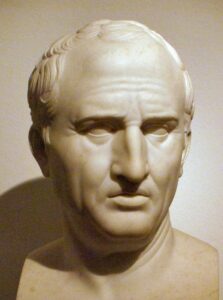

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106 – 43 BCE) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, and philosopher. He is considered a key figure in Roman intellectual history.

About the Translator

Quintus Curtius is the pen name of writer and translator George J. Thomas, who has written extensively on moral philosophy, ethics, and historical subjects.

My Rating

I found this to be a good book, but hardly a great one. I would recommend it if you read it as I did: with the purpose of understanding Cicero’s role in Stoic philosophy. If you have little to no interest in that, I wouldn’t bother.

* Vertical Knowledge: 3.5

* Horizontal Knowledge: 2.5

* Depth of Thinking: 3.0

* Literary Quality: 3.0

* Overall: 3.0 out of 4.0

The Blue Hotel

A short novel by Stephen Crane

40 pages

First published in 1898

This was an off-the-shelf read for me. An off-the-shelf read is a book that has been sitting alone and untended for years on one of the many bookshelves in one of five locations that, for whatever reason, calls out to me for attention.

I was drawn to it because of the color of the cover, the title (modest but also promising), the author (by whom I’ve only read one other book, The Red Badge of Courage, and yet I know he is considered a great American novelist), and the small size of it (a book I could read during a busy business weekend in Baltimore).

The Story

Five strangers, each on his own journey, de-board a train in Fort Romper, Nebraska, a small town at the edge of the wilderness of the American West, for a night’s rest at the Palace Hotel. Pat Scully, the hotel proprietor, persuades them to book rooms and offers them dinner.

At dinner, the men engage in small talk. Afterwards, Scully invites them to play cards, which they agree to. One of the five, referred to only as “the Swede,” is brooding and quiet at dinner, and during the card game predicts that he will die in the hotel that night.

The game resumes. But before the night is over, the Swede is indeed killed.

The rest of the story is about the fairness of the murder trial and the verdict.

What I Liked About It

I liked the story itself – the simplicity of its structure, the directness of the plot (chronological), the plainness of the prose, and the mood (brooding).

I loved the irony – the fact that the Swede comes to Fort Romper expecting to be killed because of the image he had about the violence of the Wild West, which came from reading dime-novels written by hacks who know nothing about the real West.

And I liked the way the story was written. Crane tells his stories like Hemingway does: straightforward and without sentiment or embellishment. I’ve always felt there is an inverse relationship between the sparseness of the prose and the emotional power that can come from it.

What I Didn’t Like

Nothing.

Interesting

The Blue Hotel was published in 1898 in two installments in Collier’s Weekly and has subsequently been republished in many collections. In 1977, it was made into a TV movie directed by Ján Kadár. In 1999, David Grubbs did a musical adaptation – a folk-rock album titled “The Coxcomb.”

About the Author

Stephen Crane (1871-1900) was an American poet, novelist, and short story writer. Prolific throughout his short life, he wrote notable works in the Realist tradition as well as early examples of American Naturalism and Impressionism. He is recognized by modern critics as one of the most innovative writers of his generation.

I haven’t read his poetry yet, but I’m going to.

Critical Reception

The Blue Hotel is considered to be a masterpiece – one of Crane’s finest short novels, along with Open Boat and The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky.

My Rating

* Horizontality: 3.5

* Verticality: 3.75

* Stickiness: 3.5

* Literary Richness: 4.0

* Overall: 3.75 out of 4.0

You can read the full text here – for free – on the Washington State University website.

The Last Lecture

By Randy Pausch

106 pages

Published April 2008

The title intrigued me. I looked it up and found this:

The Last Lecture by Randy Pausch, a computer science professor at Carnegie Mellon University, is a distillation of his life lessons and experiences. Written with reporter Jeffrey Zaslow, the book is an expanded version of a lecture Pausch gave in 2007 (when he was 47) after being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer.

JSN, one of the great mentors in my life, died from pancreatic cancer.

The book (and Pausch’s lecture) has two parts. The first is a lighthearted explanation of how he achieved six of his childhood dreams: experiencing zero gravity, playing in the NFL, authoring an entry in an encyclopedia, being Captain Kirk, winning stuffed animals in amusement parks, and becoming a Disney Imagineer. The second part, which is more substantial, is about how he used his experience to help others achieve their childhood dreams.

What I Liked About It

His positive attitude and upbeat energy is infectious. Most of the ideas, however mundane, are nevertheless true and important.

For example:

* We cannot change the cards we are dealt, just how we play the hand.

* How do you get people to help you? By telling the truth and being earnest.

* Apologize when you screw up and focus on other people, not on yourself.

* Remember: Brick walls exist to separate us from the people who don’t really want to achieve their dreams. Don’t bail.

* Show gratitude. (When he got tenure, he took his research team to Disney World for a week. “These people just busted their ass and got me the best job in the world for life,” he said when asked why he did it. “How could I not?”)

* Work hard. (He got tenure a year early. When asked what his secret was, he said, “It’s pretty simple. Call me any Friday night in my office at 10 o’clock and I’ll tell you.”)

* Find the best in everybody. You might have to wait a long time, but people will show you their good side. Just keep waiting, it will come out. And be prepared. Luck is truly where preparation meets opportunity.”

About the Author

Randy Pausch was a Professor of Computer Science, Human-Computer Interaction, and Design at Carnegie Mellon, where he was the co-founder of Carnegie Mellon’s Entertainment Technology Center (ETC). He was a National Science Foundation Presidential Young Investigator and a Lilly Foundation Teaching Fellow. He had sabbaticals at Walt Disney Imagineering and Electronic Arts (EA), and consulted with Google on user interface design.

Critical Reception

The book was a bestseller. The lecture, which went viral, has been viewed by millions. You can watch it here.

My Rating

* Horizontality: 2.0

* Verticality: 3.0

* Depth of Thinking: 2.5

* Literary Richness: 2.5

* Overall: 2.5 out of 4.0