When the stock market hit an all-time high on May 16 – despite the instability in the financial markets and all the obvious problems with inflation – I wondered if that might be a signal that it may be in for a tumble. Since my domain is wealth building, not stock investing, I asked Sean for his take. Apparently, it was something he had been thinking a good deal about. His reply was lengthy and detailed and replete with facts and charts that not just impressed me by the range and depth of his thinking, but made me feel a little better about the outlook for the stock market for the rest of this year. This is good stuff. Some of it may be new to you, but do yourself a favor and spend some time with it. As always, if you have questions or comments after reading it, Sean and I welcome them. – MF

“Why Is the Market Still Going Up?”

By Sean Macintyre

Whenever I start seeing this question start to surface, a part of me has to wonder: “Does that mean we’re going to have a crash soon?”

After all, one would only ask this question if there was a stark divergence between what we’re seeing in the markets and what we should expect to see.

And at the moment, stocks do seem to be defying gravity… just as they did in 2021, 2019, 2006, 1999, 1929, and so on and so forth.

The Dow just hit an all-time high of 40,000. And the S&P 500 as well as the Nasdaq have been brushing against all-time highs throughout the year.

But why?

After all, this is also happening at the same time declines in economic conditions signal that a broad slowdown may still lie ahead for the US.

According to Justyna Zabinska-La Monica, Senior Manager in charge of Business Cycle Indicators:

“Another decline in the US [Leading Economic Index] confirms that softer economic conditions lay ahead. Deterioration in consumers’ outlook on business conditions, weaker new orders, a negative yield spread, and a drop in new building permits fueled April’s decline. In addition, stock prices contributed negatively for the first time since October of last year. While the LEI’s six-month and annual growth rates no longer signal a forthcoming recession, they still point to serious headwinds to growth ahead. Indeed, elevated inflation, high interest rates, rising household debt, and depleted pandemic savings are all expected to continue weighing on the US economy in 2024.”

Basically, business conditions seem to be deteriorating, bond yield spreads are still negative, fewer business orders are coming in, less building is happening, inflation is still too high, and debt is getting out of control.

Citigroup’s chief US economist says that this gradual softening of economic conditions “tends to snowball” into a recession. He says that a hard landing – a recession that follows interest rate hikes – is inevitable.

And one of the investors who predicted the subprime-mortgage bubble, Gary Shilling, predicts a recession by the end of the year that could cause stocks to drop by as much as 30%.

Listen…

We know that stocks are not the economy, and the economy is not the stock market.

But with all the warning signs in the economy, with all the concern about an impending downturn, one must wonder why stocks keep creeping higher.

Well. I may have some answers.

I’ve actually been predicting that the market was going to go higher ever since late 2022. And in late 2023, I predicted again that stocks would climb higher in 2024. Despite and even because of some of the challenges facing the economy.

So let’s look at 7 of the plausible explanations I see for why stocks have been climbing higher over the last 18 months.

Reason No. 1:

There was a ton of cash parked with nowhere else to go – now it’s going somewhere.

In November 2023, I predicted markets would rise in 2024. This is the reasoning I gave in one of the newsletters I write for Investment College in Japan:

After the downturn of 2022, a lot of people sold their stocks. They’ve also been adding money to their retirement accounts since then.

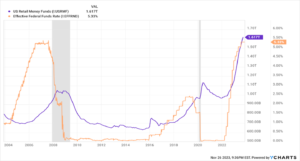

You can see how retail investor cash has piled up in money market funds every time there’s been a drop in the S&P 500 in the chart below (recessions in gray)…

Whenever stocks turn down… the money that comes from people selling their stocks goes somewhere.

And recently, that “somewhere” has been assets like CDs, gold, and money market funds. There’s $1.6 trillion of investor money just sitting in money market funds.

Why is so much money pooling in an asset that historically had a terrible return?

Ever since interest rates have risen, many money market funds have been paying over 5% since about April 2023, up from near 0% in April 2022, and Americans are liking it.

A lot.

You can clearly see the relationship between interest rates and money market funds in the chart below. After every cycle of interest rate hikes, it’s just more sensible to get paid a high income for taking on less risk.

But those are just the money market funds with retail investor money. Regular people and retirees.

There’s actually an entirely other type of money market fund that’s sold to institutions.

And these funds have seen inflows never before seen in history.

If you add up all the money in all the money market funds owned by investors and institutions…

You quickly see that, right now, there’s a $5.9 trillion mountain of money just… waiting.

[In 2024,] you can expect just an enormous wave of money to exit money market funds and flood into stock and bond markets (and real estate, for that matter).

In other newsletter issues, I also pointed out that 2024 was an election year, and election years have been historically bullish (that is, a positive catalyst) for stocks, with 11.3% returns during election years on average – a bit above the market’s long-term average.

So here’s the plausible play-by-play of what has been happening:

1. In 2022, we saw a big market sell-off. This led to a surfeit of cash sitting in money market funds earning a decent rate of return due to higher interest rates.

2. Then mega-cap tech stocks like Nvidia and Amazon bounced back in 2023, leading markets higher even while other stocks lagged.

3. Inflation moderated faster than anyone expected (which I’ll explain in more detail later).

4. The returns in 2023 far outpaced what people were getting in money market funds.

5. The financial media has been pointing out that interest rates being lowered and election years (like 2024) typically coincide with stocks going up in value.

6. Everyone who was sitting in cash, waiting for markets to fall further, felt like a sucker for playing it safe. And now they’re buying even after the initial run-up of gains.

To put it even more simply…

There was a ton of cash sitting on the sidelines. We have seen it move back into stocks – mainly tech stocks. And it seems there is still more, trillions more, left to shift over.

But you may be wondering…

If all that cash has been sitting on the sidelines looking for places to go… why is it going into stocks?

Well, leaving aside for a moment that we’re also seeing gold and other commodities rise in price, and we’re seeing real estate appreciate in price, which means that some of this money is definitely finding its way into alternatives…

For the average American, it’s basically a choice between stocks and nothing.

Reason No. 2:

Americans are forced to buy stocks and there are no easy alternatives.

In 2023, 76% of private industry workers had access to “defined contribution retirement” benefits like a 401(k).

That means that, for participants, a small chunk of every paycheck goes into a retirement account, usually selected by employers.

And guess what assets a majority of 401(k)s permit people to invest in?

Stocks. Bonds. And mutual funds that hold some combo of stocks and bonds.

A huge number of working Americans have no choice but to buy stocks on a monthly or even bimonthly basis.

And if hundreds of millions of people are buying the same thing every few weeks for years and years…

What does one expect to happen? Prices are going to go up!

Well past anything resembling a reasonable valuation.

This is why the number of 401(k) millionaires surged 43% over the past year!

And what if a large number of people decide to avoid these plans and invest on their own?

Well, there are huge incentives not to do this.

They lose out on the tax benefits of these plans, for one.

And they have to face the choice of where else to save and invest their money.

And where is that going to be?

In the previous section, I showed how money market fund interest rates weren’t beating stocks.

If you look more broadly, there’s just no good alternative to stocks for most investors right now.

Let’s take real estate, for example.

In 1981, when 30-year fixed mortgage rates exceeded 18%, the median price for a new home was $70,000.

A 20% down payment would cost about $14,000.

Considering the median family income was $22,390, it would take about 7 years of saving 10% of one’s income to buy a brand-new house. Not unreasonable!

In 2024, the median sales price for a new home is $430,700. A 20% down payment is $86,140.

The average salary in the US in 2024 is $63,795.

Saving 10% of one’s income, it’d take someone earning the median salary 13.5 years to save for a home.

And that leaves off the fact that home prices have been moving (generally) up while wages have not been keeping pace with inflation.

If you set out to become a real estate investor today, you’d end up living out the ironic plot of a Guy de Maupassant or O. Henry story…

By the time you had enough, it wouldn’t be enough anymore!

It’s the exact same story with gold.

The hourly pay for a median household in 1981 was $10.76.

One ounce of gold was worth around $400. So the cost for an ounce of gold was a little more than 37 hours of labor.

Now the median hourly earnings for a worker is about $30.67.

An ounce of gold is worth about $2,333 as I write this.

That means the straight-down-the-middle median-earning American would need to work 76 hours to buy one ounce of gold.

And these real estate and gold buying examples don’t even factor in other costs, time, dealing with brokers and dealers, etc.

We can do this for every even mildly illiquid asset. They’re all far more expensive than they used to be, and still have a high barrier to entry.

Compare that to stocks, though.

It takes 5 minutes to set up a Robinhood trading account. You can buy fractional shares of any stock – speculative or not – for as little as $1. And you can do it without any closing costs, fees, or other obstacles.

And for many workers with a 401(k), as I mentioned above, investment in stocks is completely automatic and regular.

At this particular point in history, what earthly reason does any new investor have to consider anything else?

The barrier to buying stocks is insanely low and the historical returns are insanely high.

That’s why FINRA reports that there’s a “new generation of younger investors entering the market with substantially different investment behaviors and attitudes than older generations.”

Gen Z, folks born after the year 2000, are more invested in stocks right now than any previous generation.

A Vanguard analysis observed the savings behaviors of 250,000 employees based on their ages in 2006 and 2021 and found that, in 2006, 25% of employees ages 18 to 24 had no stocks in their 401(k) plan. In 2021, 97% of employees ages 18 to 24 had invested between 41% and 99% in stocks in their 401(k) plan.

There’s no historical precedent for this.

Never before has an asset class been so easily accessible by regular people.

And never before have alternatives, assets that have traditionally produced enormous wealth (like real estate), seemed so inaccessible in comparison.

This, by the way, also gives insight into the ability of cryptocurrencies to continue marching higher.

The fractional divisibility of a cryptocurrency token allows someone with only a few bucks to speculate.

I interviewed several people recently for a video. Everyone younger than 25? They’re trading crypto and stocks. They believe it’s the smartest thing they could be doing with their money, considering they don’t have very much capital to invest in traditional assets.

“I’ll invest in index funds or real estate when I have enough money to do so,” is the common thread.

Dumb, illogical, brilliant? I have my opinions, sure.

What matters, though, is that these people are buying.

And buying makes asset prices go up.

Reason No. 3:

The economy might actually not be that bad.

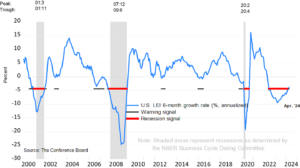

At the top of this report, I reprinted a quote from one of the folks working with NBER, the group in charge of deciding whether or not we’re in a recession.

They noted, in their recent reports, that leading indicators about the economy – the data they use to predict trouble ahead – are no longer portending doom.

Just a few months ago, economic indicators were screaming “recession ahead.” For two months now, the Conference Board’s economic indicators have no longer been signaling a recession.

And if we consider things from that perspective…

Economic conditions in the US have been gradually improving for months.

Effectively, economists are saying right now, “The patient still has a gunshot wound… but at least we’ve staunched the bleeding.”

And if we compare stock prices with an indicator like the Weekly Economic Index (a weekly snapshot of the US’s economic health), we see that stocks have been responding positively to this trend in the overall economy…

When the Weekly Economic Index hovers around its average… stock indices like the Dow trend up.

When the Economic Index trends below its average… stocks become volatile and trade sideways or down.

And since December 2022? Except for a few hiccups, the Weekly Economic Index has been stable and trending up. Same as stocks.

So is this a classic case of “Things feel worse than they actually are”?

Well, as the Conference Board says, there are some serious headwinds ahead that have people justifiably worried.

But people invest in stocks based on what they think is GOING to happen. Not the way things are.

And if enough people believe that we’ll emerge from this economic trouble unscathed? If enough people believe that interest rates and inflation are going to come down?

They’re going to invest now in the hopes of capturing those future tailwinds.

And that will drive prices up. Even before everything in the economy sorts itself out.

Reason No. 4:

Market valuations and stability are still… fine. Not great. Fine.

If we were to look at charts of US stock market valuations, we might think that we were sitting atop a precarious Jenga tower, primed to fall.

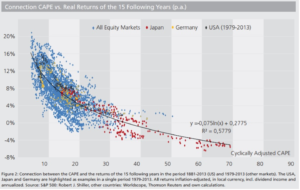

The Shiller CAPE Ratio is a Nobel-prize winning measure of how “expensive” or “cheap” the stock market is relative to corporate profits.

And by this measure, the US stock market has been bouncing around the second-most overvalued it has ever been.

The Shiller CAPE ratio gained popularity because, as a model, it is extremely predictive of stock returns looking 8 to 15 years in the future.

During periods when the CAPE ratio of the S&P 500 was high, returns over the next decade and more were quite poor.

And this is true regardless of the stock index and regardless of the country.

When you graph the CAPE on the X-axis of a chart and inflation-adjusted returns on the Y-axis, you can see a clear trend.

As you go to the right of the graph, towards a higher CAPE, you start to see poorer and poorer returns over the 15 years that follow:

But if you look quite closely, you’ll notice quite a few outliers.

For example, even when the global CAPE ratio has been worse than the US’s right now, in the 40 to 50 range…

Stocks in all equity markets still produced positive returns over the long term, when adjusted for inflation.

Worse returns than average, sure. But still positive.

In fact, based on what I said above in the section on Americans being effectively forced to buy stocks on a regular basis and there not being attractive alternatives, I strongly believe that “higher valuations” are the new normal for US stocks, at least at this point in history.

To put it bluntly, overvaluations in stocks are not really something to be afraid of.

They are something to encourage caution and diversification across different asset classes, sure.

Because think of it this way: High stock valuations create instability that makes markets vulnerable to crashes, but they do not, by themselves, cause stock market crashes.

And in the end, a market crash is not the only way stocks can move from “overvalued” to “fairly valued” in terms of the CAPE ratio.

The CAPE is ultimately still a ratio between stock prices and stock earnings.

And US corporate earnings have been trending steadily up after a small, worrisome hiccup in recent years.

If stock prices remained the same, or grew at a slower pace than corporate earnings, we will see stocks become fairly valued without ever seeing a market crash.

In truth, there’s only one number I pay attention to that tells me whether I should not buy stocks for the long term…

And that’s the Shiller Excess CAPE Yield: A measure of the returns we should expect from stocks in excess of the return you can expect from Treasury bonds.

Or to put that another way, when the CAPE Yield is positive? You’ll probably get better returns from stocks over the next decade. And when the CAPE Yield is negative? You’ll probably get better returns from bonds.

And right now? The CAPE Yield is still positive. Trending down, sure, but still positive.

By this measure, stocks and financial markets are just more attractive and appear more stable than alternatives right now.

And I say this as someone who is incredibly bullish on bonds and bond funds as we inch ever closer to interest rate cuts over the next few years.

One last point about the stability of the financial markets…

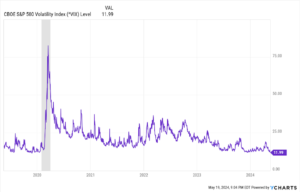

We can measure stability by looking at volatility, which is tracked by an index called the “VIX.”

Volatility is just a measure of how unpredictable, uncertain, or unstable the stock market is at any given moment.

The higher the VIX? The more stocks tend to move up or down in a surprising fashion.

The lower the VIX? The less fear, uncertainty, or doubt we see in the market.

And if we look at the VIX right now, we see something surprising…

The VIX is at its lowest level since 2019.

The market just isn’t unstable or predictable right now.

And when volatility declines, stocks tend to trend up, simply because uncertainty tends to scare investors into selling (and vice versa).

Reason No. 5:

All the fear around high inflation might be entirely overblown.

The legendary investor Warren Buffett once said, “Inflation swindles almost everybody.” And that’s true whether they are a stock investor, a bond investor, or a “cash-under-the-mattress person.”

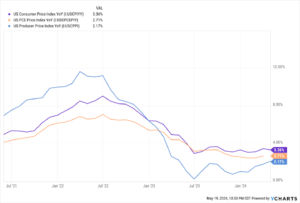

And what we see, if we look at three different measures of inflation, is that while things have gotten better, we’re still not out of the woods yet.

Whether we’re looking at Consumer Price Index inflation, Personal Consumption Expenditure inflation, or Producer Price Index inflation…

We want them all to be around 2%, give or take.

At the moment, they’re all just a little too high for anyone’s comfort. This is why central banks around the world increased interest rates…

The hope is that slowing down economic growth will slow the growth of consumer prices, personal expenditures, or producer prices.

All of which, by the way, are a proxy for what we’re really trying to measure when we talk about inflation: The loss of a currency’s purchasing power.

Why does this matter?

Because when currencies lose their purchasing power, real corporate and economic growth becomes more and more difficult.

An economy with high inflation is like a long-time heroin addict.

An addict gets accustomed to the dose. And then they need more and more heroin to have the same effect.

It’s a similar story with high inflation: Money loses its potency, and so you need more and more of it to accomplish the same thing as before – whether that’s purchasing goods or investing to grow a business.

Now, about three years ago I built a model and have since successfully predicted future inflation to within a single percentage point.

I predicted the looming rise of inflation in mid-2021. I predicted the decline of inflation from its highs in 2022.

And in September 2023, I predicted that inflation was going to stay stubbornly high.

The reason why is not particularly hard to understand…

1. What is causing the recent round of inflation? Too much money in the economy and not enough stuff to satisfy demand.

2. What’s the solution? Less money and more stuff.

3. What is the Federal Reserve doing to lessen the amount of money? With quantitative tightening and higher interest rates, we’ve seen the US money supply declining and economic activity slow down.

4. What can the Fed do to help people get more stuff? Even though the Federal Reserve can print and destroy money… what it cannot do is print factories, apartment buildings, or mines.

So what will solve the inflation problem?

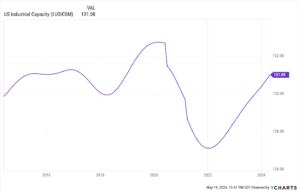

Simple: Businesses increasing capacity and producing more, which they are doing, or people going broke and losing their job and demanding less stuff, which might be starting to slowly happen.

Industrial capacity in the US has been recovering from 2022 lows (when inflation was highest) and recently reattained pre-pandemic levels.

There’s our stuff. If industrial capacity remains high or goes higher, it should help curb inflation.

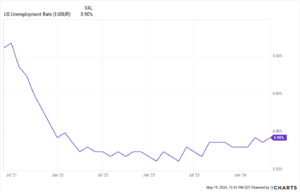

Then there’s demand, which unemployment directly impacts.

And we see, too, that unemployment has been ticking very slowly higher since inflation was really bad in mid-2022.

To sum it up, what we might be seeing right now is the slow self-correction of the inflation problem.

We have plateaued in the fight against inflation, to be sure. But right now we’re seeing incremental changes month after month that seem to suggest we’ll see lower inflation in the future, with some minor setbacks along the way.

At least, that’s the case for now.

But the question remains… If inflation has remained high, why have stocks continued to go higher?

Well, here’s what academic research suggests:

Unexpected spikes in inflation cause stock prices to go down, which happened in 2022.

Unexpected decreases in inflation cause stock prices to go up, which happened in 2023.

That’s the short term. Long term, a lot of early hypotheses in the 1970s suggested that inflation was bad for stock prices.

But studies in the 1990s found that, while high inflation led to poor returns over about a one-year investment period, stocks can actually provide an excellent long-term hedge against inflation.

That’s because stock valuations depend on corporate profits. Corporate profits can increase in inflation because they can justifiably charge higher prices, which is what happened in 2022 and 2023.

The period from late 2021 to late 2022 was about one year. That’s when we saw inflation peak… and it’s also when we saw stocks decline the most.

Another recent study found that stock prices go up when interest rates go up. Which happened just before 2023, when stocks started to take off.

Based on these more recent studies, everything we’ve seen has lined up nicely with what we should expect from stocks in inflationary periods.

But here’s another interesting observation I found while researching this piece…

In 2020 and 2021, one of the major concerns about the market was the prevalence of what are called “zombie corporations.”

That is, companies that do not generate enough revenue to pay off their spiraling debts. These companies are effectively “dead” but still operating.

I wrote about this extensively in 2020.

But studies find that high inflation actually provides a lifeline to these highly indebted companies.

Why? Because a company’s debt is a fixed amount of money growing at a fixed rate.

Inflation can disproportionately increase a company’s revenue relative to its debt.

This gives us a good, plausible reason why we haven’t seen the huge waves of bankruptcies everyone expected over the last 5 years.

Highly indebted companies have actually benefited from high inflation… and this, of course, would bolster their stock prices.

Reason No. 6:

All the concerns around dedollarization might be overblown and premature… plus it might actually turn out to be a positive catalyst for US stocks.

The US dollar became the world’s reserve currency – that is, the currency most countries hold and use to settle international trade – in 1944, with the Bretton Woods conference.

The US dollar was pegged to gold (convertible at $35 an ounce) and other nations had fixed, but adjustable, exchange rates to the dollar.

The system ended in August 1971 when President Richard Nixon “temporarily” suspended the dollar’s convertibility to gold, which became permanent by 1973.

After that, major currencies around the world have not had some tangible thing that they represent.

Currencies are valued based on how they float against each other.

Since the collapse of the Bretton Woods system and the end of the gold standard, there has been no international agreement in place to hold the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency…

Countries have simply done it because it has been the most convenient and prudent thing to do.

Dollars are commonplace, easy to get and sell, and relatively stable compared to other currencies.

There is a belief, however, that at some point the US dollar will not hold this position as the world’s reserve currency. Many believe that the US’s global supremacy is intrinsically tied to the dollar’s supremacy.

Here is what they believe will happen when dedollarization occurs:

If the dollar loses its status, debt will spiral out of control, some say, because the lower demand for US Treasury bonds will necessitate higher interest rates.

Higher interest rates means higher borrowing costs, which puts the US into a debt spiral and at risk for default.

On top of that, if the US dollar loses its reserve status, the dollar might lose value relative to other currencies. This would increase the cost of importing goods (which the US does a lot of), causing inflation to skyrocket.

And finally, folks believe that the US dollar losing its reserve status will cause financial markets to become incredibly volatile. Investors and major institutions would adjust their portfolios to account for currency valuations. Additionally, US Treasury bonds are considered a “risk-free investment” right now, but would not be in this scenario.

Okay, now you know the context and you understand the fears around dedollarization.

These fears have reached a fever pitch ever since the BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, and others) have been discussing the possibility of creating a common currency to compete with the dollar.

There are three quibbles I have with this whole thesis. Especially when it comes to how this will affect stock prices.

The first quibble I have with the dedollarization argument is causal:

Does the stock market’s returns depend on the US being the world’s reserve currency?

This one is easy to answer. We just need to find a period of time when stocks did fine despite the US dollar not being the world’s reserve currency.

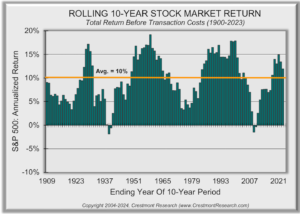

And that’s exactly what we see.

Even though the US suffered a severe depression in the 1930s…

The average 10-year returns for the stock market were still almost entirely positive. And within the same range we’ve seen over the last 120 years.

To put it another way: Markets behaved more or less the same whether the US was the reserve currency or not, whether the gold standard existed or not.

Returns in the market, like business cycles, go up and down over time. And these crests and troughs seem to have very little to do with the US dollar’s status.

So while there might be some short-term churn and volatility if the US dollar were to lose its status as the world’s reserve currency…

I don’t think there’s really any evidence to suggest that it will be cataclysmic. Or even anything other than part of the normal noise of the markets.

My second quibble is historical:

In all this talk of alternative currencies taking over the status of the US dollar, or BRICS countries no longer using dollars in trade, I haven’t heard many people discuss the simple fact that we’ve already lived through a period where this was normal.

The Soviet ruble was used for trade within the Soviet Bloc during the Cold War, and it was not convertible with US dollars.

The Soviet Union also established the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON) to compete with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank. It aimed to coordinate economic policies, facilitate trade, and improve industrial development between socialist countries.

COMECON helped facilitate ruble-denominated transactions between socialist countries.

To put it bluntly: Even when the US dollar was the de facto, agreed-upon world’s reserve currency… it wasn’t the reserve currency for the whole world.

The US economy and currency has already survived and thrived during a period of stark divisions and high competition.

Another thing…

When the euro emerged, people were talking, then, about dedollarization as well.

I found an article written in the Vancouver Sun back in 1999 that talked about how the euro was likely to unseat the dollar as the world’s reserve currency, shifting the balance of global power to Europe.

It has been 25 years. The euro has not replaced the dollar.

Let’s say there is a new BRICS currency…

Let’s ignore the fact that the BRICS countries do not even really get along with each other and are unlikely to ever succeed in this endeavor…

It’ll be just like the euro. Not the world’s reserve currency, but one of many reserve currencies.

And due to the interconnected nature of global economies and trade, if there is a BRICS currency, there will be a high likelihood that it will be convertible with US dollars…

Which means that central banks in BRICS nations will still probably need to hold US dollars in reserve!

Simply put, the future that people fear, with economic divisions and multiple reserve currencies…

It’s all something we’ve already lived through. And the US economy (and stock market) grew regardless.

My third quibble is practical:

I wonder: “Is the US dollar losing its position in the world any time soon?”

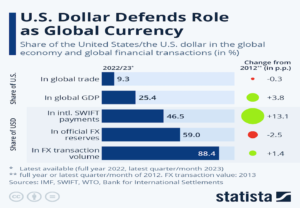

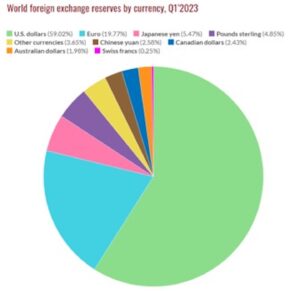

If we look at the data, I do not see a world on the cusp of dedollarization.

The US dollar’s role in international payments and foreign exchange transactions has been gaining over the last 10 years.

In July 2023, right around the time that the BRICS met to discuss an alternate world order…

International bank payments denominated in US dollars reached an all-time high.

For all the talk of dedollarization and settling international transactions in local currencies… the dollar still dominates. We have not yet seen this trend reverse course.

As recently as a year ago, Warren Buffett even stated, “I see no option for any other currency to be the reserve currency.”

Another investor I hold in high esteem, Seth Klarman, had this to say in 2022:

“The Euro is an experiment. There’s no adjustment mechanism. There not any real money clout behind it. Japan’s got severe problems, demographic in particular. So it’s not like the Yen seems like such a great place to be. The Swiss Franc is too small to be a global currency. So the US has had an enormous advantage being the world’s reserve currency for a very long time. It’s unlikely to change any time soon. It’s hard to imagine people accepting Chinese currency. It’s hard to imagine people accepting cryptocurrency. There’s just too many uncertainties. While the US isn’t perfect, it’s been an important player on the world stage and a protector of the liberal world order, and I don’t see that role changing.”

But we have to ask…

Will this go on? Will the US dollar remain the world’s reserve currency forever? Will the US continue to be a global economic superpower?

No. All empires fall. All cities will one day lie in dust.

But that is the long run. And as John Maynard Keynes once noted, “The long run is a misleading guide to current affairs. In the long run we are all dead.”

In the meantime, we’re talking about some really well-established, highly entrenched systems, here. Major changes to financial systems take a long time, lots of money, and a ton of international coordination.

I can see the US dollar losing its primacy in 40 to 50 years as other countries like China and India become larger and larger participants in global trade and GDP…

But as long as the US remains a global power in the top 5? Even the top 10?

Countries will need dollars and dollar-denominated assets, like treasury bills…

And they’ll need them for the same reason that the US Federal Reserve Bank holds about $12 billion in euro-denominated assets and about $6.6 billion in Japanese-yen denominated assets.

Heck, for all the talk of the United Kingdom suffering as a result of losing its status as the world’s reserve currency in the first half of the 20th century…

The pound sterling is still the fourth most commonly held reserve currency on the planet, behind the euro and yen.

Grand sweeping changes to the global economy and geopolitical power dynamics take decades to play out. Sometimes centuries. (The Roman Empire was in decline longer than it was ever in a position of power.)

And even when these changes happen? They rarely happen in absolute terms.

Things happen gradually and with nuance.

So “dedollarization” is just something I’m not worried about in my lifetime.

Nor does it seem like a major catalyst for stock returns, positive or negative.

Plus, there’s an easy way to defend against fear of a worst-case scenario: Hold some gold and silver, hold some savings in a few foreign currencies, hold some property, hold a diverse basket of stocks that generate revenues internationally, tell your family you love them, pet your dog, try to be happy, and only worry about what you can control.

Which takes me to the final reason I believe stocks are going up…

Reason No. 7:

Stocks go up because stocks go up.

There is almost a tautological relationship between stock prices and what drives them.

Stock prices go up because people make stock prices go up.

See, stocks are all sold at auction. That means stock prices only go up for one reason: People are willing to bid up prices.

That’s it. That’s the real reason.

The Dow hit 40,000 and all the other major indices are nearing all-time highs because people are paying higher prices for indices’ constituent stocks.

I wish there was a grander story or narrative here. I was as disappointed in the reality as you probably are.

“Surely,” I hear you cry, “it cannot be that simple.”

I wish there was more to it, believe me.

It would certainly make the thousands of hours I spent learning financial modeling feel more useful.

But this is why bubbles happen. It is also why incredibly underpriced markets happen. And it is the reason behind everything else in between.

As Yuval Harari said, “Humans think in stories, and we try to make sense of the world by telling stories.”

This is true for investment analysis as well.

That’s not to say that any of it is made up or fake.

Au contraire. A story that motivates human behavior en masse is no different than reality.

If you own a stock and hundreds of thousands of people decide to sell that stock because they see a quadruple inverted unicorn horn pattern with a sparkling confetti Bollinger Band squeeze…

The value of your investment still goes down. Regardless of the quality of the story people are acting on.

So, ultimately, it makes no sense to ask why prices are going higher and higher.

What we really need to be asking about are the stories that motivate human (and institutional) behavior. We have to understand human psychology and how large groups of humans might be behaving based on their perceptions of the world.

All the reasons I’ve given you above?

They’re stories. Stories with plenty of counterexamples and alternative interpretations.

Doesn’t matter which story is true, or which interpretation is true.

We know that the aggregate of all the stories right now is motivating people to buy stocks.

That’s what matters. That’s the why.

So whether we look at the stability of the financial markets, inflation, or threats against the US dollar…

I do not see any reasons why stocks would not go up in the near term.

There’s the possibility that we might see near-corrections, like we did in April. There’s a possibility we might even see a recession and another bear market in the coming months or years.

If we do, it will be because the stories people are acting on have changed.

And none of these possibilities pose an existential threat to investors or the stock market overall.

And for well-positioned investors with a long-term mindset and good, diverse investments across asset classes…

They should be fine even in the event of a downturn, like we saw in 2020 or 2022.

In fact, such a downturn might even be an opportunity to buy more stocks to further compound your wealth.

That’s a story I firmly believe in.

And so far, it’s been working well for me and everyone else I know who believes it.