Reminder: A Change Is Coming

As I said on Tuesday, I’ve decided to start publishing this blog once a week instead of twice. So, starting next week, you can expect to receive one somewhat longer issue that will include more of the investment advice and commentary on the economy that my readers have been asking for.

Question: Would you rather receive it on Monday, Wednesday, or Friday?

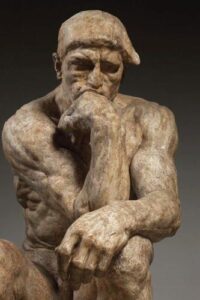

Things I’ve Been Thinking About Lately

A Lesson I Learned Long Ago About Personal Relationships. How long have you been hoping that your friend would stop with that annoying habit he or she has had as long as you can remember? Or that your spouse would improve himself or herself in some way that would be more appealing to you and also better for him or her? How many times have you made a subtle suggestion, or a tactical criticism, or a simple plea for him or her to do something about whatever it is that’s bothering you? And how many of those efforts by you were successful?

We know the answer. Never or very rarely. And that’s because by the time Homo sapiens arrive at adulthood, 95+% of their instincts, emotional intelligence, reactions, behaviors, and habits are deeply etched into their brains.

That means you will have less than a 5% chance of ever being able to “help” a friend or spouse “improve” themself in any meaningful way. In other words, spending time, energy, and effort on trying to change anyone in your life is 95+% futile.

When I came to this conclusion, I realized that I had a choice. I could continue to try to encourage change in the people in my life and deal with the eventual disappointment years later when they did not change. Or I could accept the idea that they would not change and learn to accept them – even love them – for who they are.

There are all sorts of rational objections one could make against this approach. I know. I spent years making them. But to no avail. I ended up angry and resentful and eventually losing those personal relationships I had once valued.

Turns Out, This Is True in Business Relationships. Recently, at a business meeting, my partners and I were discussing the strengths and weaknesses of a number of our leading executives. We were talking about the various strengths and weaknesses these people bring to their jobs, and how much better they could be if they could learn to stop doing this or start doing that.

I was participating in the conversation willingly and happily when I suddenly realized that we’d been having basically the same conversation about these same execs at least a half-dozen times over the previous three or four years.

I challenged my partners with a thought experiment. “Assume, for a moment,” I said, “that no matter how much we urge them, inform them, or incentivize them, none of them will be able to change. Imagine that we had a crystal ball… that we looked five years into the future and saw that none of them had made a single substantial change. If that were the case… what would we be talking about today?”

The next ten minutes of our discussion were more rewarding than the dozens of hours we had spent devising strategies to evoke changes in these people that were never going to come.

Exceptions Don’t Prove the Rule. We can, to a significant degree, help our children terminate unwanted behaviors and develop desirable ones. Nature designed Homo sapiens to be mentally and emotionally malleable when they are young. So, although it may not seem possible, studies have shown that up to about 15 or 16 years of age, teenagers can make those positive behavioral changes. But by the time people reach adulthood, their habits and tendencies are too deeply engrained.

There are some exceptions. There are always some exceptions. But if you want to solve a problem, and especially a big, complicated problem, it makes zero sense to continue with or even double-down on a “solution” that has been failing for the majority of those involved for many years.

And yet, that is exactly what we do. We create programs – local, regional, and federal programs – that promise to solve a problem but never do. In fact, they often make matters worse! But instead of acknowledging and accepting the failure of the “solutions,” we conclude that the way to fix the failure is to spend more money on the programs. To do more of them or do them “harder.”

I’m talking about a very wide range of social “problems” here – from the failure of our educational institutions to educate, to the failure of our addiction programs to reduce drug and alcohol addiction, to our failure to reform criminals in the penal justice system.