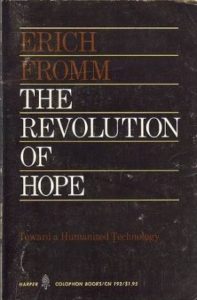

The Revolution of Hope

By Erich Fromm

162 pages

First edition published Jan. 1, 1968 by Harper Row

I first heard about Erich Fromm when I was in college, in the late 1960s. Fromm’s most popular book, The Art of Loving, was on the reading list for Sociology 101.

I remember being impressed by it. Or wanting to be impressed by it. My sociology professor, whom I admired, praised it. That was good enough for me.

A few weeks ago, I found, in a box in my garage, an old copy of another of Fromm’s books: The Revolution of Hope. I gave it a read, wanting to see how 50 years of life experience might have altered my youthful adulation.

I can see how Fromm’s work was so attractive to my professor back then. And what an effect it had on intellectuals of my generation.

As was true of every social philosopher at the time, Fromm was influenced by Freud and Marx. In The Revolution off Hope, he shows himself to be both an admirer of them and an independent thinker. He shares their generally gloomy outlook on humankind. But he rejects their commonly held view that the human condition is determined by exterior factors. For Freud, those factors were the unconscious and biological drives. For Marx, they were systemic social and economic forces.

Fromm offers a more humanistic view. He argues that man has the ability, through force of will, to cut his own, self-determined path in life.

It is from that perspective that he writes about hope:

“Hope is paradoxical. It is neither passive waiting nor is it unrealistic forcing of circumstances that cannot occur…. To hope means to be ready at every moment for that which is not yet born, and yet not become desperate if there is no birth in our lifetime. There is no sense in hoping for that which already exists or for that which cannot be. Those whose hope is weak settle down for comfort or for violence; those whose hope is strong see and cherish all signs of new life and are ready every moment to help the birth of that which is ready to be born.”

There were many times in reading The Revolution of Hope that I was reminded of Sartre, whom I read a great deal of in graduate school. Fromm seems to see existence, as Sartre did, as a battle between being and nothingness. What distinguishes us from the other animals is free will. And that condemns us to spend our lives resisting the social, economic, and biological forces that, unopposed, would render us passive instruments of authoritarian culture and fascist politics.

There is much in The Revolution of Hope that I was not persuaded by, including Fromm’s limited (and I’d say naïve) understanding of capitalism. In his efforts to bowdlerize Marx, he could be said to be the father of contemporary liberal thinking.

But when Fromm writes about human agency, about not just the potential but the obligation of the individual to think his own thoughts and take his own actions, I find myself, once again, an admirer.

About Erich Fromm

Erich Fromm (1900-1980) was a German social psychologist, psychoanalyst, humanistic philosopher, and democratic socialist. He was associated with what became known as the Frankfurt School of critical theory. His best-known work, Escape from Freedom (1941), focuses on the human urge to seek a source of authority and control. Fromm’s critique of the modern political order and capitalist system led him to seek insights from medieval feudalism. His many works (in English) include Psychoanalysis and Religion (1950), The Art of Loving (1956), and On Being Human (1997). (Source: Wikipedia)