Problems With NFTs

NFTs are hot, especially in the art world. But it’s highly unlikely they will get to the next level, so long as there are reports of them being stolen.

Such as this one. Click here.

And this one. Click here.

Problems With NFTs

NFTs are hot, especially in the art world. But it’s highly unlikely they will get to the next level, so long as there are reports of them being stolen.

Such as this one. Click here.

And this one. Click here.

More on the Buyer Brain

After my Feb. 14 essay on the “Buyer Brain,” several readers wrote to ask me to elaborate and provide examples. To catch you up: In that essay, I pointed out that, with respect to buying decisions, it is useful to understand the human brain in terms of three distinct parts – the reptilian brain, the limbic brain, and the neocortical brain, representing instinct, emotion, and thought.

My thesis was that, to compete in the 22nd-century digital marketplace, CEOS, copywriters, and marketers will have to take a holistic approach to the sales process, including marketing to prospects, onboarding new customers, and serving existing ones. Prior to the internet, general advertising companies could dominate their markets by focusing their marketing on instinct and emotion. Likewise, direct marketing companies could grow huge by focusing on emotion and thinking (i.e., rationalization). Today, every business of every kind must appeal to and satisfy all three parts of the brain.

Below, I answer two questions that account for most of those I received…

From BP, a direct marketer – re my claim that direct marketers need to appeal to instinct (the lizard brain):

“I’m thinking that the lizard brain might be the ad, or some image/headline that immediately makes someone stop and pay attention. Some kind of pattern interrupt of sorts, since the lizard brain is basically scanning for something new and different to pay attention to because, in the past, it could be a lion waiting to attack you. Can you give a few examples?”

My answer: Exactly. With the hundreds of micro-messages a typical consumer is exposed to on the internet every day, it’s no longer possible to capture attention with headlines like “How to Lose 20 pounds in 10 Days.” Such a promise could underline the pitch, but to distinguish your ad from so many others, you have to do more than that. Something that stops the casual reader in his tracks – if only for a second. There are several ways to do that. Some are verbal – usually single words that feel somehow wrong or out of place. And some are visual – images, photos, even typefaces that are in some way jarring. Of course, it’s not enough to simply interrupt. The rhetorical device you choose must also appeal to a lizard instinct. For a moment, and only a moment, it must scare him like a snake in the grass or allure him like an irresistible aroma.

From KB, a general advertising executive:

“You said that people in my line of work understand instinct and emotion. I get that. How does the neocortical brain come into play?”

My answer: In the pre-internet days, goods marketing via general advertising sent people into stores where real live salespeople closed the sale and then sent customers home to experience their purchases. Nowadays, more and more goods are simply delivered directly from the distributor to the customer. This directness means that all sorts of things the salesperson did to convince the customer that she made a good purchase are missing. So, to keep refunds down and repeat buying high, general advertisers will be asked to do much more: to create materials that will help customers rationalize their purchases ex post facto.

Noteworthy: About the Stock Market

Since the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the average market drawdown from geopolitical shocks has been just 5%. And the market bottomed, on average, 22 days later and recovered within 47 days.

One example: The 9/11 terrorist attacks on the US sent the S&P 500 down 4.9% in one day and 11.6% overall. But the market bottomed just 11 days later and recovered in one month.

As my friend and colleague Alex Green pointed out recently: “Corrections and bear markets are great opportunities to accumulate positions in companies that are likely to outperform when the market bounces back.”

Interesting: About Life Expectancy in the US

The states with the highest life expectancy are Hawaii, California, New York, Minnesota, and Massachusetts. The states with the lowest life expectancy are Tennessee, Kentucky, Alabama, West Virginia, and Mississippi. Overall, Americans are expected to liver 78.8 years.

(Findings based on death rates in 2019.)

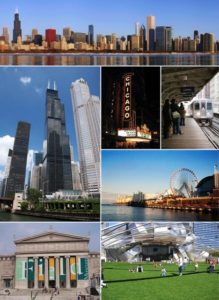

Chicago

I spent most of the summer of 2007 in Chicago, working on Ready, Fire, Aim. I needed to be away from home for several months to focus on finishing the book. That need dovetailed with a longstanding dream I had about getting to know some of the great cities of the world by living in them for more than just a few weeks.

I’ve been writing a bit lately about what a sh*thole Chicago has become. In fairness, my current assessment of the city is based on reading reports on the upswing in crime and how poorly the mayor has been handling it.

But I remember Chicago as a great city. A city that had nearly everything that New York had to offer, but cleaner and with nicer people. A big city with big-city amenities, but without the pretension and high costs. (And I remember it as a place where I think I did some of my best writing.)

What I like about Chicago:

* The arts – Chicago has, as I said, everything that NYC offers.

* The shopping – I don’t know how it is now with all the crime, but North Michigan Avenue (the “Magnificent Mile”) boasts as many great stores as anywhere else.

* The architecture – from Louis Sullivan to Mies van der Rohe and Frank Lloyd Wright.

* The music – Chicago is known not only for jazz, but also the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Lyric Opera.

* The parks.

* The beach.

Christie’s started off the spring auction season strongly with a three-part auction in London and Shanghai, racking up $334 million in works from the 20th and 21st centuries.

Die Fucshe (“The Foxes”), a 1913 painting by Franz Marc, fetched the highest price of $57 million. (This was a restitution piece stolen by the Nazis during WWII.)

And an untitled triptych by Francis Bacon – that I would have bought if I were 100 times richer – went to a lone phone bidder for $47.6 million.

“Many situations in life are similar to going on a hike: the view changes once you start walking. You don’t need all the answers right now. New paths will reveal themselves if you have the courage to get started.” – James Clear

Susurrus (suh-SUR-us) – a word that sounds like what it means – is a low, soft whispering, murmuring, or rustling sound. (Plural is susurruses.) Example from The Journal of a Disappointed Man by W.N.P. Barbellion: “They are the susurrus of the breeze before the storm, and you await what is to follow with palpitating heart.”

Re the Feb. 23 issue on Depression:

“Your article on Depression and the rating system that you’ve developed are extraordinarily accurate and helpful for readers. At this point in my life I believe it is a hormonal and cosmic energy imbalance. However, when I was in my 40s, I was hovering between 4 and 4.2 for a long time. Spent lots of money on therapies that didn’t seem to help beyond giving me something to do and someplace I was supposed to go. Thank you for sharing.” – MF

Re my Indulgence Diet:

“Love this! I have to try it.” – DB

Why I keep doing what I do:

“I was sitting down to write you a letter but I’ll just say it in this email: I really appreciate you and all you have done for me over the years. I know you are a mentor to countless copywriters and have had a major influence on the profession. But you have always been an influence and role model to me, as well. I owe you thanks and I do thank you. If there’s something I can do for you, you have only to let me know.” – BB

From The Innocence Project: Stop the Execution of Melissa Lucio in Texas

On April 27, Melissa Lucio is scheduled to be executed by the State of Texas for a crime that never occurred. Melissa’s 2-year-old daughter, Mariah, died tragically two days after accidentally falling down a flight of stairs. Despite the fact that Melissa had no history of child abuse and that she has maintained her innocence for the 14 years she’s spent on death row, the State still has her scheduled for execution. You can read more about Melissa’s case here, but we also need your support to stop her execution and prevent an irreversible injustice. Will you add your name right now to stop Texas from killing Melissa or text SAVEMELISSA to 97016?

How to Be Good at Group Decision-Making…

and Why It Really Matters

In making personal decisions, I’ve always followed a simple, two-step protocol.

* Step One: Figure out what I want to do.

* Step Two: Do it.

That worked well and still works well for me as a sovereign individual. But I am also a part of many groups – businesses, teams, clubs, families – for which decision-making happens as a group. For these decisions, in my younger days, I followed a four-step protocol.

* Step One: Figure out what I want to do.

* Step Two: Try to persuade those affected by my idea that it will be good for them.

* Step Three: If they agree, do it.

* Step Four: If they don’t agree, do it anyway.

As you can imagine, this approach had its plusses and its minuses. As I aged, and as the group decisions I had to make became more numerous, the minuses began to outweigh the plusses. I was obliged then to add some other components to my group decision-making process. Like listening. Alas, listening, it turns out, is a necessary part of good group decision-making. You never know. Listen and you just might hear something you need to know.

Lately, as I mentioned in the Feb. 16 issue, I’ve been learning more about group decision-making as a part of my family’s estate planning. I’ve been reading essays and articles. I’ve been watching videos. And I’ve been talking to friends and colleagues.

I’ve come to the conclusion that there is indeed a sort of science to good group decision-making. By that I mean there seem to be reliable strategies based on human nature that make for wiser decisions and happier outcomes.

I’m going to be writing more about all of this in future issues. Today, I want to touch on four things I’ve discovered:

If you had asked me a week ago how many decisions I make on a typical day, I’d say six to 12, including small decisions. But yesterday, with this essay in mind, I actually kept track of every decision I made from 6:30 in the morning till 5:30 p.m.

How many did I make? Six? Twelve? Twenty?

The answer was 96!

About half of them were borderline meaningless. (“Should I shave now or when I get to the office?”) Many were somewhat significant. (“Should I listen to Howard Stern or ‘Enlightenment Now’ driving to and from work?”) And some – I counted 16 – I categorized as important. That surprised me!

I asked myself how many of those decisions were group decisions. The answer was about 32. Also more than I expected. Then I looked at those 32 group decisions to determine how many individual decision-making groups they represented. The answer was also surprising: 16!

If I were to count all non-duplicate groups (of two or more) as individual groups, the total number of decision-making groups of which I’m a part would probably be many times 16. Most of these groups rarely have to make decisions, and many of them make decisions that aren’t terribly important. But I was able to identify eight groups whose decisions are very important to me.

Three of them are businesses (whose earnings and equity have a direct impact on my family’s wealth). Three are non-profit foundations (whose legacy I deeply care about). One is our family “office,” including K, our boys, and their spouses (and whose decisions will affect the future wealth and happiness of the family). And finally, there is the smallest but most important decision-making group I belong to: my partnership with K.

All those different entities. All those different goals. All those different personalities. Each must have its own particular strategy for effective “corporate governance” (as the Rogersons call it). Serious issues: Time. Money. Love. So much to gain if the decisions are good. So much to lose if the decisions are bad.

In the Feb 16 issue, I wrote about how I hired Tom and Cathy Rogerson to help our extended family make wise decisions about the family’s future. By participating in several workshops run by the Rogersons, one of the things we learned is that we all have different “love languages” (what sort of things makes us feel loved) and equally different leadership styles (director, counselor, analyst, persuader).

Each of these are ingrained aspects of our emotional intelligences. Each of them affects how we understand one another and express ourselves. Prior to this training, conversations about family topics (ranging from “Where Shall We Have the Next Family Reunion?” to “Who Should Be in Charge of the Family’s Cryptocurrency Portfolio?”) might have been laden with subtle psychological landmines. But now, knowing and respecting the differences in our perceptions and styles of communication, we can have such conversations with less stress and more success.

But there is another thing that comes into play during group decision-making conversations. This is something that is rarely discussed in conversations about communication. And almost never discussed in conversations about decision-making.

Long before Ken Hudson’s book Speed Thinking was published, I had noticed that in business meetings some people were always quick with their ideas and conclusions, while others were always slow.

I came to think of the quick people as fast thinkers and the others as slow thinkers. At first, I believed that fast thinkers were better thinkers. And that made me feel good, because I always thought of myself as a fast thinker.

But as time went on and I reflected on the decisions made in the many group conversations I’ve had over the years, I came to realize that the early thoughts weren’t always the best thoughts – and that to make the best decisions, you have to find a way to involve both fast and slow thinkers whenever you can.

So, what do I mean by fast and slow thinkers?

By fast thinkers, I mean people that are always first to come up with new ideas and first to suggest solutions to problems that arise. Fast thinkers are good at idea flow, because they feel good when ideas are flowing quickly and are impatient when they are not. Fast thinkers are uncomfortable with slowness generally. Their ability to think quickly can be seen as a coping mechanism for their impatience.

Slow thinkers are skeptical of new ideas. They rarely come up with them, and are usually late to the party when the theme is about solving problems. They are good at critical analysis. They enjoy checking and double-checking assumptions. They are uncomfortable with deadlines and uncomfortable with speed generally. And they really don’t like to make mistakes. Slow thinkers prefer to take a measured pace, bringing in one new piece of information at a time. Before they utter a word, they want to feel like they have examined the problem or opportunity from every reasonable perspective. They have no interest in getting where they want to go quickly. They want to think carefully. Find the best possible solution. Above all, they believe that the way to be right is not to be wrong.

Fast thinkers find slow thinkers frustrating. Slow thinkers find fast thinkers irritating. In business meetings, fast thinkers will typically dominate the conversation and wield more power. Slow thinkers tend to respond to this by becoming passively aggressive. And worse, feeling bullied and shut out, they may put their intelligence into criticizing or even sabotaging the fast thinkers’ proposals.

This is not a formula for decision-making success.

Fast-Slow Partnering: My Whole-Brain Strategy for Group Decision-Making

As I said, I consider myself a fast thinker. In discussions about problems – business or personal, theoretical or practical – I’m invariably the first one to offer solutions. And when the conversation is about a challenge, I’m the first one to come up with a plan.

In decision-making groups where I don’t have a thinking partner, I usually dominate the conversation and get my way. In decision-making groups where I do have a partner, I also tend to dominate… initially. But as the conversation continues, my slower-thinking partners often get their way.

Here’s the thing: When I don’t have a “slow-thinking” partner, my idea-to-success ratio is about 50%. When I do, it’s much higher.

So, considering all of the above, I have come to the conclusion that the ideal situation for decision-making is to have partners whose thinking speed is contrary to yours.

If you are a slow thinker (analytical), you will tend to reject the ideas of fast thinkers because they will come too quickly, too abundantly for your comfort. They will also be rough-hewn, because fast thinkers usually share them the moment they have them. But it is a mistake to voice your objections to their ideas the moment you hear them. Be patient. There will be time for criticism later.

If you are a fast thinker, you will likely feel like you are not just the first, but often the only person to come up with ideas in brainstorming sessions. This is probably because you are overwhelming the slow thinkers with your barrage of half-baked ideas. After your first volley, take a pause and ask others for their suggestions. If there are none, finish your proposal and schedule a follow-up session. Make it clear that the purpose of that meeting will be to consider alternative ideas. (Expect the slow thinkers to come prepared.)

So, what do you think of my theory on fast and slow thinking? Tell me quick! I want to know now!