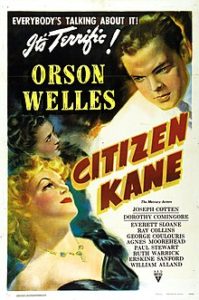

Citizen Kane

Release date: 1941

Directed by Orson Welles

Starring Orson Welles, Joseph Cotten, Dorothy Comingore, and Agnes Moorehead

Available on several streaming services, including Netflix and Amazon Prime

Citizen Kane is revered by many critics. And yet, it was not a big hit with the public. Even from a P&L perspective, it was a flop.

Still, if any movie deserves to be considered an auteur film, it’s Citizen Kane. Orson Welles not only starred in it, but produced it, directed it, cast it, and co-wrote the screenplay.

The movie was heralded as revolutionary in many ways, including the cinematography, the lighting, and the staging. But many of the innovations were, according to Welles, a product of his ignorance. Being new to the movie business, he had no idea of what “could not be done.” And thanks to his stature as an actor, instead of telling him that certain things couldn’t be done, his crew went ahead and figured out how to do them.

Other lauded “innovations” – in terms of mood and music – were simply homages to the techniques of little-known European directors, in particular, the German expressionists that Welles admired.

What I Liked About Citizen Kane

* The ambition of the story: The tragic portrayal of a larger-than-life man, and a depiction of America during a key era of its history.

* The ambition of its genre: It attempts to be a classic tragedy, and mostly succeeds.

* Its thematic dimensions: It explores both the culture of the times and the psychology of the man.

* The set design: Theatrically impressive. Even breathtaking at times.

* The photography: Disturbing at times, unsettling often, but always engaging.

* The acting – especially Welles’s charismatic interpretation of Kane.

What I Didn’t Like So Much

* The flashback structure didn’t quite work for me. Flashbacks are commonplace now. And when done well, they enhance the plot. But in Citizen Kane, they seemed, at times, artificial.

* From a horizontal perspective, Citizen Kane is very good. It gave me a good sense of so many elements of US society back then. From a vertical perspective, however, it was unsatisfying. It gave me only a superficial sense of who this character really was, what motivated him, etc.

Interesting

* Orson Welles got credit for writing the screenplay, but he had employed a script writer, Herman J. Mankiewicz, to shape his voluminous notes. The screenplay won an Academy Award that was shared by both men, but not before Mankiewicz had to threaten Welles with a lawsuit in order to get him to agree to giving him co-credit. (A Netflix movie – Mank – was made about this recently.)

* Although it was a critical success, Citizen Kane failed to recoup its costs at the box office. The film faded from view after its release, but returned to public attention when it was praised by French critics and re-released in 1956.

* Charles Foster Kane, the protagonist, was a composite character based mainly on media tycoon William Randolph Hearst. Hearst hated the movie and tried to shut it down. He was particularly angry about the movie’s depiction of a character based on his mistress, Marion Davies, a former showgirl whom he had tried to make into a Hollywood star.

* Rosebud was the trade name of the cheap little sled that Kane was playing with on the day he was taken away from his home and his mother. It is believed that it was also a reference to Hearst’s pet name for Davies: “tender button.”

* Hearst Castle, the main residence of an estate in San Simeon, California, that originally belonged to Hearst, was the inspiration for the “Xanadu” mansion in Citizen Kane. However, the estate was not used as a location for the film.

* Historically speaking, Xanadu, the first capital of the Mongol Empire, was established by Kublai Khan (1260-1294), the first emperor of China’s Yuan dynasty. Famous for its palaces, gardens, and waterways, it has come to stand for an idealized place of magnificence and beauty.

Critical Reception

For 50 consecutive years, Citizen Kane stood at number one in the British Film Institute’s poll of critics. It was number one in the American Film Institute’s list of the 100 best American movies in 1998, as well as its 2007 update.

* “Citizen Kane is far and away the most surprising and cinematically exciting motion picture to be seen here in many a moon… it comes close to being the most sensational film ever made in Hollywood.” (Bosley Crowther, NYT)

* “Citizen Kane is a film possessing the sure dollar mark, which distinguishes every daring entertainment venture that is created by a workman who is a master of the technique and mechanics of his medium. It is a two-hour show, filled to the last minute with brilliant incident unreeled in method and effects that sparkle with originality and invention. Within the trade, Kane will stimulate keener creative efforts by Hollywood’s top directors.” (John C. Flinn, Sr., Variety)

You can watch the trailer here.