A friend, “Billy Sunshine,” whose birthday will be celebrated soon, asked his guests to sing “Happy Birthday” this way:

Apocalypse Now

Originally released in 1979

Now available on various streaming services, including Netflix and Amazon Prime

Directed by Francis Ford Coppola

Starring Marlon Brando, Robert Duvall, and Martin Sheen

“Why would you watch a movie you’ve already seen?” K asked me.

Sometimes she does that – asks me questions that leave me temporarily speechless. I gathered my thoughts.

“For the same reason I have read Sapiens twice and Lolita three times.”

“Don’t be snarky,” she scolded.

I get it.

There are so damn many good and even very good new movies being produced. More now than ever. And many times more than one could possibly view. Why waste precious time watching something for the second time?

My answer is simple: There is a huge difference between very good and great.

The first time I saw Apocalypse Now was the year it was released, 1979. I was 29, working as a journalist in Washington, DC. It was soon after I had returned from a two-year stint in Africa as a Peace Corps volunteer, and 12 years after I was called to serve in Vietnam by my local draft board. (Another story for another time.)

Apocalypse Now is a three-hour war drama, a brilliant reimagining of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, and probably Francis Ford Coppola’s best film. It’s also one of a dozen movies I’d take with me to the proverbial “desert island.” (We can talk about the other 11 in a future post.)

The photography and the musical score are brilliant. The sets, scenery, sound effects, and editing are superb. But it is the script and the acting that bring an otherwise very good war film to the level of greatness.

Critical Reception

In reviewing Apocalypse Now in 1999, Roger Ebert encapsulated my thoughts:

At a distance of 20 years, Apocalypse Now is more clearly than ever one of the key films of the century. Most films are lucky to contain a single great sequence. Apocalypse Now strings together one after another, with the river journey as the connecting link.

The whole movie is a journey toward Willard’s understanding of how Kurtz, one of the Army’s best soldiers, penetrated the reality of war to such a depth that he could not look any longer without madness and despair…. It is the best Vietnam film, one of the greatest of all films, because it pushes beyond the others, into the dark places of the soul. It is not about war so much as about how war reveals truths we would be happy never to discover.

Interesting fact: At the time of its release, the producers were criticized for paying Brando a million dollars for what amounted to about five minutes of screen time. How wrong they were.

You can watch the trailer here.

Rationality: What It Is, Why It Seems Scarce, Why It Matters

By Steven Pinker

432 pages

Published Sept. 28, 2021 by Viking

His name kept coming up in conversations. Good conversations.

“I’ve never read him,” I admitted.

I’d get that “Are-you-kidding-me?” look.

I googled.

Turns out that Steven Pinker is a professor of psychology at Harvard University. He’s also a member of the National Academy of Sciences and a two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist. He was named one of Time’s 100 Most Influential People, and one of Foreign Policy’s 100 Leading Global Thinkers.

His books include The Blank Slate, The Stuff of Thought, The Better Angels of Our Nature, The Sense of Style, Enlightenment Now, and Rationality. I started with the newest one, the full title of which is Rationality: What It Is, Why It Seems Scarce, Why It Matters.

Given Pinker’s impressive intellectual credentials, I was prepared for a tough read. But the book begins quite gently, with a review of some of the better-known probability puzzles.

Like this one (known as “The Monty Hall Problem”):

A contestant is faced with three doors. Behind one of them is a sleek new car. Behind the other two are goats. The contestant picks a door – say, Door #1. To build suspense, Monty opens one of the other two doors – say, Door #3 – revealing a goat. To build the suspense still further, he gives the contestant an opportunity either to stick with the original choice or switch to the unopened door. You are the contestant. What should you do?

Correct answer: You should open another door. It’s a game show, silly. It’s designed to keep up the suspense.

And this one:

Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken, and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations. Which is more probable? 1, Linda is a bank teller. Or, 2, Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement.

Correct answer: She is a bank teller. (Most people pick 2, even though it’s mathematically impossible for it to be more probable.)

I was pretty sure I knew the “rational” answers to all of the puzzles, since I’d encountered them before. Instead, either because I’d forgotten or because I’d never double-checked my answers, I was wrong about every one.

Pinker’s explanations of the correct answers were lucid and enlightening and fun. After that, I was all in. And to my delight, he then took his talent for connecting reason to common sense and applied it to all sorts of contemporary issues, including Critical Race Theory and other intellectual constructs of Woke Culture.

I haven’t finished the book yet, but here are some examples of what I’ve found so far that I thought not just smart but brave:

In 2020 the brutal murder of George Floyd, an unarmed African-American man, by a white police officer led to massive protests and the sudden adoption of a radical academic doctrine, Critical Race Theory, by universities, newspapers, and corporations. These upheavals were driven by the impression that African-Americans are at serious risk of being killed by the police. Yet as with terrorism and school shootings, the numbers are surprising. A total of 65 unarmed Americans of all races are killed by the police in an average year, of which 23 are African-American, which is around three-tenths of one percent of the 7,500 African-American homicide victims.

….

A second sphere in which we cannot rationally forbid base rates is the understanding of social phenomena. If the sex ratio in a professional field is not 50-50, does that prove its gatekeepers are trying to keep women out, or might there be a difference in the base rate of women trying to get in? If mortgage lenders turn down minority applicants at higher rates, are they racist, or might they… be using base rates for defaulting from different neighborhoods that just happen to correlate with race?

A recurring theme of Rationality is that when it comes to difficult conversations, facts must be the common material, and logic must be the guiding rule. Unfortunately, Pinker says, these core elements of rationality have been all but abandoned at most US universities.

A major reason for the mistrust is the universities’ suffocating left-wing monoculture, with its punishment of students and professors who question dogmas on gender, race, culture, genetics, colonialism, and sexual identity and orientation. Universities have turned themselves into laughingstocks for their assaults on common sense.

Reasoned argument, Pinker asserts, has been replaced by sophistry riddled with the most basic logical fallacies.

* Ad hominem: “You don’t know because you are a privileged white man.”

* Genetic: “I can’t believe you because your facts came from Fox News.”

* Affective: “What you are saying is wrong because it hurts my feelings.”

Sometimes, Pinker says, the ad hominem and genetic fallacies are combined to forge chains of guilt by association. He gives this example: “Williams’ theory must be repudiated because he spoke at a conference organized by someone who published a volume containing a chapter written by someone who said something racist.”

As I said, I haven’t finished the book – but so far, I’m liking it. It’s engaging. It’s knowledgeable. And it makes sense.

Actually, I’m amazed that this book was published in the first place and that Pinker is still holding a job.

Critical Reception

* “An impassioned and zippy introduction to the tools of rational thought…. Punchy, funny, and invigorating.” (The [London] Times)

* “Pinker competes with venerable thinkers like Noam Chomsky, Jared Diamond, Charles Murray, Thomas Sowell, Francis Fukuyama, and so forth for the mythical title of America’s Top Public Intellectual.” (Steve Sailor in Taki’s Magazine)

“Erudite, lucid, funny, and dense with fascinating material.” (The Washington Post)

One of my favorite “Karen” videos…

My Old-World Perspective on Investing

I am a happy member of two discussion groups: The Mules, a book club, which meets monthly, and Whiskey Wednesdays, a sort of old-fashioned conversation salon, that meets weekly.

One of the many topics we come back to on Wednesdays is the current state and future of technology. Last week, we talked about NFTs. SS, my partner in Ford Fine Art, was saying that someone approached her recently, offering to make NFTs out of some of my Central American collection.

If you haven’t heard of NFTs, you should know that they’ve become the thing futurists have been talking about almost non-stop for more than a year now. NFT stands for “non-fungible token.” Like cryptocurrencies, they are produced on the blockchain. Unlike cryptos, they are not used as currencies, but as digital assets. (I’ve mentioned them several times here on the blog.)

SS knows that NFTs have made their way into the art scene. And she’s heard the stories of overnight riches – including the one about the NFT by the artist known as Beeple that sold at Christie’s for $69.3 million on March 11. But she also knows my approach to buying art – which is skeptical and conservative. So on the one hand, she was tempted by this opportunity. But on the other hand, as she put it, “I don’t know shit about NFTs.”

NE, the youngest member of the group, thought it sounded like a great idea. But he sees things from a different perspective than the rest of us. He believes that there’s been a fundamental change in the way the world works. Something that has everything to do with the rapid movement towards the brave new world of the metaverse. “We are at a flexion point,” he said. “It’s like the transition from horse-drawn carriages to gas-powered automobiles. You have to see the writing on the wall. We are now with NFTs where we were with cryptocurrencies 10 years ago. Imagine if you could have invested in Bitcoin back then.”

This naturally led to a discussion about investing in general. And, although NE’s confidence in cryptocurrencies and NFTs could prove to be right, I wanted to explain my old-world perspective on investing to him…

A Bird in the Hand

My Approach to Building Wealth

When I think about investing – whether it is investing my time or my money – I begin by asking myself: What sort of thing is it that I’d be investing in?

Is it a business – like Agora Publishing or Microsoft? Or is it a financial asset – like gold or Bitcoin or a work of art?

I make this distinction because it is very fundamental to how I think about wealth building.

There is a big difference between investing in a business and investing in any other sort of financial asset.

A business is more than a financial thing whose value fluctuates based on supply and demand. A business is dynamic and operates with motivation and intent. It functions as a natural organism, like a plant or an animal, because it is a natural organism, composed, as it is, by natural beings.

A business has a purpose – which is to sell its products and services at a profit. It does this through constant change and adaptability to the environment within which it exists. Cash flow is its life blood. Customer satisfaction is its inevitable and evolutionary purpose. And profit is how it measures its health.

Financial assets like gold or cryptocurrencies do not function as natural organisms. They are not conscious. They have no intrinsic purpose. They are not capable of making a profit. Their value depends entirely on how much, at any given time, people are willing to pay for them.

Investments vs. Speculations

When I buy stocks, I am buying shares in ongoing businesses. When I buy corporate bonds, I am making loans to such businesses. I call these sorts of transactions investments.

When I buy gold (as I have) or cryptocurrencies (as I have) or art (as I do all the time), I am buying an asset whose value I hope will appreciate. The chance of that happening depends not on anything the asset does, but on the buying public’s perception of its value. However clever I think I may be in guessing future demand for the asset, I don’t have any real idea of whether that will happen. I don’t know its revenue history or its P/E ratio because it has none. For that reason, I consider such transactions to be speculations.

Prudent wealth building, in my view, is a matter of giving preference to transactions whose outcomes are relatively predictable. And that means investments that I can understand relatively well and, if at all possible, have some control over.

These two factors – knowledge and control – are how I rate my likelihood of success in making all my financial decisions.

Another way of thinking about this is to look at wealth building opportunities in terms of appreciation and income. When I buy a work of art or a parcel of undeveloped land, I am hoping that its value will appreciate. When I buy a bond, I am counting on the income it will give me over time.

I would much prefer owning a building I can rent out than a parcel of land, because the former provides both income and potential appreciation, while the latter gives me only the possibility of value gain.

My favorite investments are those that offer both income and appreciation and that I fairly well understand and at least partially control.

That doesn’t mean I don’t speculate. I do. But I try to keep the balance between investments and speculations to about 80/20.

Among the speculations I’ve made over the years, some – especially those that have a long history of appreciating – have proven more reliable than others. Gold is such a speculation. It isn’t a business. It doesn’t produce income. But it is considered by the entire world to be a store of value and it has a 2,000-year history of maintaining its value. That makes gold (and other precious metals) a priori safer than cryptocurrencies. I can say the same thing about art.

But between those two, I prefer my art because there is absolutely nothing I can do to affect the price of gold, whereas there is something I can do (promotion and advertising) to increase the value of my art.

If I were to show you my portfolios of financial assets, you would see a direct correlation between the amounts I have invested in each and the four factors of knowledge/control and income/appreciation.

The largest portion of my wealth resides in income-producing businesses. After that is rental real estate. Both portfolios provide me with all four factors.

Below that – in terms of the percentage of my net worth – are my stock portfolios, which provide both income and appreciation, and about which I can know something, but over which I have no control. Then I have my bonds, which are like owning businesses, but without the appreciation.

Below stocks and bonds are all my speculations. My favorite is art, because, as I said, I know a good deal about the art I buy and I can, to some extent, affect the price I get for it. After that, it’s gold. I have no control over its value, and it provides no income. But though it may not skyrocket in value, it’s more than likely to hold its own.

And then, below these assets, are such things as cryptocurrencies and (if I end up investing in any) NFTs. I put these at the bottom because they aren’t businesses, they don’t create profits, they don’t provide income, and the possibility that they will appreciate is entirely out of my hands.

To Be Sure…

I get why many people like NE are so excited about the rapid advances in technology that are creating new money-making opportunities like cryptocurrencies and NFTs. Huge fortunes have always been made by speculating on future trends.

But it’s not in my nature to use my time and money that way. My wealth-building philosophy is summed up in a very simple phrase: “A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.”

Mine is not a strategy to get very rich, very quickly. But it does offer the advantage of a great degree of relative safety, where you can pretty much guarantee (engineer) that your wealth will continue to grow, year after year.

I did invest cryptocurrencies – five of them – several years ago. And they have appreciated by more than 600%, which is something my more conservative investments have rarely, if ever, done. And, yes, I sometimes think I wish I had invested more than one-tenth of 1% of my net worth in them. But then I remind myself: My bird-in-the-hand strategy for building wealth has served me well over the years.

I will continue to speculate now and then when someone like NE presents a persuasive case. But when I do, I will assume that I’m going to lose all of my money. With that thought in mind to begin with, I can enjoy the ride without needing a positive outcome.

At first I thought this was yet another entry for The Darwin Awards. In fact, it’s a demonstration of how adept some people are in managing backhoes.

Howl and Other Poems

By Allen Ginsberg

57 pages

Originally published by Lawrence Ferlinghetti (City Lights Books) in 1956

After church service, but before we were allowed to go out on Sundays, my mother required us to recite a poem she had given us the previous morning. In my early years, I memorized such poems as “The Owl and the Pussy Cat.” In my adolescent years, I was able to choose what I put to memory. They tended to be poems like “The Highwayman”by Alfred Noyes and “Richard Cory” by Edwin Arlington Robinson.

It was not until I was in college that I first read a “modern” poem. And the first one I read, Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl,” was a life changer.

I try to read a book a week. Last week, I didn’t have time to start and finish another one. But while browsing through a bookshelf in K’s office, I came across the very copy of “Howl” that I first read in 1969. And I was delighted to discover that it had marginalia and lines that I had starred or underlined.

So you can get a feel for this poem, in case you’ve never read it, here are a few of the passages that I had highlighted…

From Part I

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness,

starving hysterical naked,

for an angry fix,

angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly

connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night,

who poverty and tatters and hollow-eyed and high sat up

smoking in the supernatural darkness of cold-water flats

floating across the tops of cities contemplating jazz…

… who broke down crying in white gymnasiums naked and

trembling before the machinery of other skeletons,

who bit detectives in the neck and shrieked with delight in

policecars for committing no crime but their own wild

cooking pederasty and intoxication,

who howled on their knees in the subway and were dragged off

the roof waving genitals and manuscripts,

who let themselves be fucked in the ass by saintly motorcyclists,

and screamed with joy,

who blew and were blown by those human seraphim, the sailors,

caresses of Atlantic and Caribbean love…

From Part II

What sphinx of cement and aluminum bashed open their skulls

and ate up their brains and imagination?

Moloch! Solitude! Filth! Ugliness! Ashcans and unobtainable

dollars! Children screaming under the stairways! Boys sobbing

in armies! Old men weeping in the parks!

Moloch! Moloch! Nightmare of Moloch! Moloch the loveless!

Mental Moloch! Moloch the heavy judger of men!

Moloch the incomprehensible prison! Moloch the crossbone

soulless jailhouse and Congress of sorrows! Moloch whose

buildings are judgment! Moloch the vast stone of war!

Moloch the stunned governments!

Moloch whose mind is pure machinery! Moloch whose blood is

running money! Moloch whose fingers are ten armies!

Moloch whose breast is a cannibal dynamo! Moloch whose

ear is a smoking tomb!…dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking

As you may have gathered from the above excerpts, “Howl” is a bit of a confessional poem. It brims with details that are now nostalgic of Ginsberg’s life as a key figure of the Beat Generation.

He first presented “Howl” at a poetry reading at Six Gallery bookstore in San Francisco. In the audience was Lawrence Ferlinghetti, a fellow writer and co-founder of City Lights Bookstore, who went on to publish “Howl” in a small paperback. Less than two years later, Ferlinghetti was arrested for publishing and selling copies of the poem, which had been deemed obscene. Though the case was widely publicized, a judge ultimately ruled that the poem displayed “redeeming social importance,” and Ferlinghetti was found not guilty. Today, it’s considered a seminal work of American literature.

I agree!

Bright Star

Initially released in 2009

Now available on various streaming services, including Netflix and Amazon Prime

Directed by Jane Campion

Starring Abbie Cornish, Ben Whishaw, Paul Schneider, and Kerry Fox

I was in a certain mood. It got a certain review. I read Keats’ poetry in college and graduate school and I remembered admiring it. I remembered that he died young.

Bright Star is the story of the relationship between John Keats and Fanny Brawn during the last several years of the young poet’s life.

What I Liked

The best thing about Bright Star is that you get to hear some of Keats’ poetry. And hearing it read aloud, as it is in this movie, is worth doing. It got me back to reading Keats. For that reason alone, I’d recommend it. Another positive is that it reminded me of how many of our greatest artists died before they were 30. Keats was obsessed with achieving immortality through his poetry. He died thinking he had failed.

What I Didn’t Like

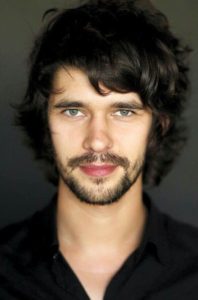

Bright Star doesn’t teach us much, if anything, about Keats’ life or the world of poetry in England at the time. It raises some interesting questions about 19th century English society, but answers none of them. It is a movie about a Romantic poet, and it is done in a romantic way. The lead actor (Ben Whishaw) is beautiful and has a beautiful voice. I don’t know anything about Keats’ voice, but there are many painted images of him that make him appear to be a few points lower on the good-looking scale. But, you judge for yourself:

John Keats

Critical Reception

* “Director Jane Campion’s most enthralling film since The Piano.” (Caryn James, Marie Claire)

* “Wonderful attention is paid to detail, including clothing, furniture and highly-stylized behavior. What is missing is emotion.” (Ed Koch, The Atlantic)

* “Yes, it is a thing of beauty and, yes, things of beauty are joys forever, but we can also probably say this about them: they don’t always add up to the most affecting movies.” (Deborah Ross, The Spectator)

You can watch the trailer here.

Note: If, as happened to me, watching Bright Star spurs you to know more about John Keats, there are many good books available. But since this is a movie review, you might want to check out a one-hour documentary about Keats produced by Encyclopedia Britannica. There are also several little videos available on one of his most famous poems, “Ode on a Grecian Urn.”

A British colleague, commenting on surprisingly good marketing results last quarter, said, “Who needs Paul the Octopus (RIP).” I had no idea what that meant. So I looked it up.

Pretty interesting! Click here.