Back Home in Florida After a Week in Paris

It’s good to be home. Back, after an impromptu week in Paris, to our family home in Delray Beach.

Paris is as unlike Delray Beach as a dinner of steak au poivre and haricot verts is to a drive-thru, McDonald’s lunch of a cheeseburger with fries.

It is absolutely one of the most beautiful cities in the world. This is partly due to the architecture – the fact that so many of its buildings were constructed during the reign of Napoleon I (1800-1815), when neoclassical elegance and symmetry were still in vogue. But it is probably chiefly due to the city planning that was done under Napoleon III (1848-1870) by Baron Haussmann, who created the boulevards and parks.

And a nod must be given to French culture, too – conservative and sometimes priggish, and committed to preserving and maintaining Paris’s magnificent old buildings.

I’ve loved Paris since I first saw her, in 1976, en route to a two-year Peace Corps stint in Africa. K and I spent part of our honeymoon in Paris nine months later, and we’ve been back to the City of Lights at least 20 times. Every time a pleasure.

When traveling to any foreign destination, we’ve learned that two important things to consider are the weather and the length of time you will be staying.

The weather during our week in Paris this time was not very good – overcast most days with periodic showers and a temperature mostly in the 60s and low 70s. But we made the best of it by planning an indoor itinerary: a gluttony of museums. And because this was such a short trip, we did what we’ve learned to do whenever we have a limited amount of time to spend in any great city. We hit the usual suspects like the locals do.

If we have just a weekend and the city is new to us, we adhere to the “three-days-in-wherever” guides that are ubiquitous in bookstores and online. Most of their suggestions are for what are considered by some to be tourist traps. But they are tourist traps for a good reason: They are the places that you really should see!

If, for example, you are in New York for the first time and have only three days, you should visit the Met and the MOMA or the Guggenheim, walk or take a carriage ride through Central Park, check out a few galleries in SoHo, and have a hot dog in Times Square.

If you are in Paris for just a weekend, you should spend a couple of hours in the Louvre, stroll through the Tuileries, check out the Pompidou Center, and have a café noisette or a drink at the George Cinq hotel.

If you have a week to spend, as we did, you should go to most of these same spots, even if you’ve seen them before. As I said, they are in the guidebooks for a good reason. They are worth seeing not just once, but over and over again. And if you are a veteran of the city, you will enjoy them with more focus, and still have time for the somewhat less traveled (but still touristy) “musts” like Bryant Park in New York and Place des Vosges in Paris.

If you are lucky enough to be able to spend several weeks or longer in a city – well, good for you. When you have that much time, you don’t feel pressured to pack so much into every day. You can enjoy a more leisurely pace – perhaps doing a single touristy thing each day. And the rest of the time, you can live more or less the way the city’s denizens do – working, shopping, and relaxing. Absorbing the city by osmosis rather than by injection.

After being away from Paris for nearly five years, I would have preferred to do it that way this time. Other obligations made it impossible, but we were happy to do what we could with the week we had.

Some recommendations, in case you are thinking of going…

The Louvre

The Louvre is, I think, the world’s largest art museum, as well as a historic monument. It is perhaps best known for being the home of the Mona Lisa, but it has impressive collections of a dozen periods and genres, from ancient to medieval to modern art. Its strength is its European collections, but it has great Greek and Roman art, a fair collection of African art, and a smattering of New World art, as well. A Parisian landmark, it is located on the Right Bank of the Seine.

We spent three hours there, revisiting the French and Italian collections of the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries. That was more than enough for us to feel sated.

An interesting note about the Louvre: Before it became the most-visited art museum in the world, it was a fortress built by King Philip II in the 12th century to deter oncoming attacks. Remnants of this fort are still visible in the basement level of the building (called the “Medieval Louvre”). The Louvre became a public museum during the French Revolution, opening its doors on August 10, 1793. Its iconic pyramid was added in 1989, and became the new main entrance.

Jardin de Tuileries (Tuileries Garden)

The Tuileries is located between the Louvre and the Place de la Concorde. Created by Catherine de’ Medici as the garden of the Tuileries Palace in 1564, it was opened to the public in 1667 and became a public park after the French Revolution.

You can get a good sense of the wonder of the Tuileries in an hour or two. We spent that mostly walking, but we sat down for a half-hour at one of the cafés conveniently located in the middle of the gardens to watch an air show that was taking place – a rehearsal for the official show that was to take place the following day, July 14 (Bastille Day, France’s national holiday).

Musée d’Orsay

The Musée d’Orsay is located on the Left Bank of the Seine. It is housed in the former Gare d’Orsay, a Beaux-Arts style railway station built between 1898 and 1900. It features mostly French art dating from 1848 to 1914, including paintings, sculptures, furniture, and photography.

We spent most of our time revisiting its collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist masterpieces (the largest in the world), by painters including Berthe Morisot, Monet, Manet, Degas, Renoir, Cézanne, Seurat, Sisley, Gauguin, and Van Gogh. We also saw an exhibition of Swiss Impressionists that I very much enjoyed. Like Latin American modernist art, the paintings were clearly influenced by the French Impressionists, but generally dated about 20 years later.

La Samaritaine

La Samaritaine is a huge department store – seven floors and two interlinking buildings. It is worthy of a visit because of its elegant Art Nouveau architecture. But it was especially fun to see it this time because it was recently remodeled from bottom to top and is now a masterpiece of interior decoration, as well as a storehouse of great haute couture fashion.

Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain

We spent one rainy morning at the Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain (more simply, Fondation Cartier), a contemporary art museum located on a wide, tree-lined boulevard.

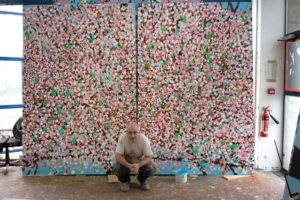

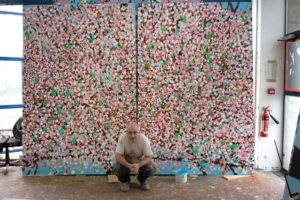

We were there for “Cherry Blossoms,” an exhibition of several dozen very large paintings by Damien Hirst, the artist that made himself famous for embedding dead animals in polymer, decorating ebony skulls, and painting polka dots.

As you can tell, I’m not a huge fan of his work. (But I do think he’s a brilliant marketer.)

Here he is squatting in front of one of the pieces we saw:

Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti (Giacometti House)

I’m a huge Giacometti fan. So, when K suggested we take a tour of Giacometti House, an old apartment-building-turned-museum where he rented a studio for the last several decades of his life, I said, “Yes!” Just like that… with an exclamation point.

It is a small museum, but it is wonderful for several reasons. The Art Nouveau-inspired interior has been preserved, and the 300-square-foot, ground floor studio is staged as if Giacometti is still in residence.

Best of all, every nook and cranny displays examples of his great gift.

The theme of the museum when we visited was Giacometti’s interest in Egyptian art and artifacts, which was made abundantly clear by more than a dozen arrangements like this one:

Musée d’Art Moderne

As a collector of modern art, I insist on spending at least a few hours in the modern art museum of every city I visit. This was the third of fourth time we’d been to the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris. It was well worth it.

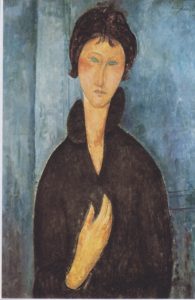

The museum’s collections include more than 15,000 works from art movements of the 20th century. Exhibitions usually focus on European trends. The exhibitions when we were there did not interest us, but there was so much more to enjoy. Like these two treasures:

La Ville de Paris by Robert Delaunay

Portrait of a Young Woman by Amadeo Modigliani

Palais Galliera

The Palais Galliera is a museum of fashion and fashion history. That may not sound terribly exciting, but if you’re a longtime reader you know that I am captivated by the great figures of haute couture. One of the best museum shows I ever saw was that of Alexander McQueen at the Met. (It went all over the world.)

On this trip, we were able to check out the work of Coco Chanel, a true early 20th century pioneer.

The first part of the exhibition is chronological – from her little black dresses and sporty models of the Roaring Twenties to her sophisticated dresses of the 1930s. The second part of the exhibition is themed: the braided tweed suit, the two-tone pumps, the quilted bag, and the costume and fine jewelry that is still intrinsic to the Chanel look.

The Chanel show was much more limited than the McQueen, and her artistic comfort range was much narrower than his… but it was still a very exciting way to spend a late afternoon on this all-too-brief trip to this amazing city.