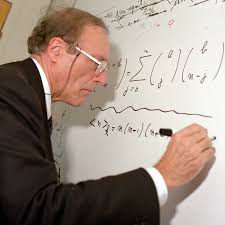

Gian-Carlo Rota was mathematician, teacher, and philosopher who spent most of his career at MIT, teaching functional analysis, probability theory, phenomenology, and combinatorics. He was the only person ever to be appointed Professor of Applied Mathematics and Philosophy.

He was respected by his peers and loved by his students. Late in his career, he wrote a series of lectures and essays about what he’d learned over the years, lessons that I found in reading them to apply not just to teaching but to business and almost every realm of endeavor.

Some examples:

| Dr. Rota: “The most brilliant students will invariably work out all the problems and let other students copy, and I pretend to be annoyed when I learn that this has happened. But I know that by making the effort to understand the solution of a truly difficult problem discovered by one of their peers, students learn more than they would by working out some less demanding exercise.”

The business lesson: 80% of the best work ideas will come from 20% of your employees.

Dr. Rota: “Half a century ago, the philosopher Gilbert Ryle discussed the difference between knowing-how courses [mathematics, the exact sciences, engineering, foreign languages, playing a musical instrument, sports] and knowing-what courses [history, the arts, the humanities, social sciences]. At MIT, knowing-how classes are more highly regarded…. And yet knowing-what courses are often more memorable. A serious study of the history of the United States Constitution or King Lear may well leave a stronger imprint on a student’s character than a course in thermodynamics…. “It is a fact, confirmed by the history of science since Galileo and Newton, that the more theoretical and removed from immediate applications a scientific topic appears to be, the more likely it is to eventually find the most striking practical applications.” The business lesson: When hiring, give preference to those with a good theoretical knowledge of how your industry works rather than those with good pragmatic knowledge of how to do a particular job.

Dr. Rota: “Many freshmen students enter MIT as naïfs and leave, after four vigorous years of education, just as naïve…. “More than a few MIT graduates are shocked by their first contact with the professional world after graduation. There is a wide gap between the realities of business, medicine, law, or applied engineering, for example, and the universe of scientific objectivity and theoretical constructs that is MIT.” The business lesson: Be careful about hiring directly from the “ivory tower.”

Dr. Rota: “You don’t have to be a genius to do creative work. The idea of genius elaborated during the Romantic Age [late 18th and 19th centuries] has done harm to education. It is demoralizing to give a young person role models of Beethoven, Einstein, and Feynman, presented as saintly figures who moved from insight to insight without a misstep…. “The drive for excellence and achievement that one finds everywhere at MIT has the democratic effect of placing teachers and students on the same level, where competence is appreciated irrespective of its provenance. Students learn that some of the best ideas arise in groups of scientists and engineers working together, and the source of these ideas can seldom be pinned on specific individuals.” The business lesson: Genius matters, but not as much as common sense, ambition, and persistence.

Dr. Rota: “Some students arrive at MIT with a career plan. Many don’t, but it actually doesn’t matter very much either way. Some of the foremost computer scientists of our day received their doctorates in mathematical logic, a branch of mathematics that was once considered farthest removed from applications but that turned out instead to be the key to the development of present-day software. “The skills the market demands, both in research and industry, are subject to capricious shifts. New professions will be created, and old professions will become obsolete within the span of a few years. Therefore, the best curriculum to follow is one that focuses less on current occupational skills than on those fundamental areas of science and engineering that are least likely to be affected by technological changes.” The business lesson: Don’t feel compelled to follow a particular career plan. Stay flexible. Allow your career to find you. |