“Art is primordially eternal.” – Egon Schiele

A Record-Breaking Year for Art

Once a year, I like to make a quick survey of the art market to get a feeling for its current health and future direction. 2020 was a very strong year, with all sorts of records broken, including some of the highest sales in history.

Take a look…

- Inspired by the Oresteia of Aeschylus (1981)

Francis Bacon

One of the 28 large-format triptychs created by Francis Bacon between 1962 and 1991, it rang up the highest sale price of 2020. It was described in Sotheby’s pre-auction literature as “rife with tragic allusion and fraught with chilling grandeur.”

Final 2020 sale price: $84.55 million at Sotheby’s New York on June 29.

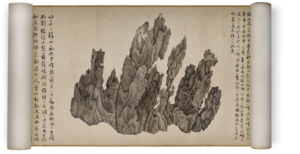

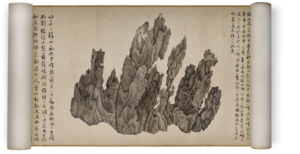

- Ten Views of a Lingbi Stone (1610)

Wu Bin

Created during the Ming dynasty by the court painter Wu Bin, this 11-meter-long scroll depicts 10 views of a single stone from a famous site in China. It set an auction record for Chinese paintings/calligraphy.

Final 2020 sale price: $76.6 million at Poly International in Beijing on July 10.

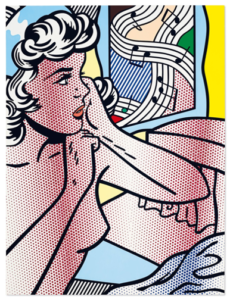

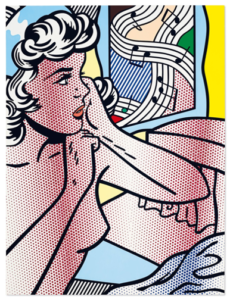

- Nude With Joyous Painting (1994)

Roy Lichtenstein

Painted toward the end of Lichtenstein’s career, this piece had never before been offered at auction. It was estimated to sell for around $30 million.

Final 2020 sale price: $46.2 million at Christie’s New York on July 10.

- Five Drunken Princes Returning on Horseback (late 13th/ early 14th century)

Ren Renfa

This rare, two-meter-long, 700-year-old scroll tells the story of five drunken princes (including one who became the longest-reigning emperor of the Tang dynasty) and their attendants on their way home. Once owned by Chinese emperors, it was moved from the Forbidden City in 1922 by Pu Yi, the last emperor of China, after the fall of the Qing dynasty.

Final 2020 sale price: $39.5 million at Sotheby’s Hong Kong on October 8.

- Untitled (1969)

Cy Twombly

From Twombly’s “Bolsena” series, one of 14 large paintings done in August and September of 1969 when Twombly was living in a house overlooking the lake of Bolsena north of Rome. According to the artist, some of the images in the series allude to the July 1969 Apollo space flight/ moon landing. This painting previously sold at auction in 1992 (to New York dealer Larry Gagosian) for $1.65 million.

Final 2020 sale price: $38.7 million at Christie’s New York on October 6.

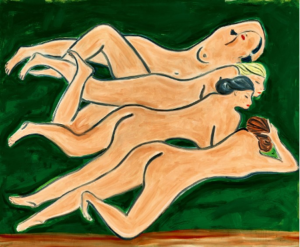

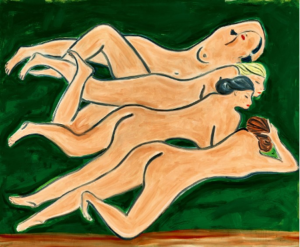

- Quatre Nus (1950)

Sanyu

Sanyu, the “Chinese Matisse,” was unrecognized in his lifetime. He died, destitute, in Paris in 1966. But now, prices for his work have been soaring. This piece, for example, previously sold in 2005 for “only” $2.1 million.

Final 2020 sale price: $33.3 million at Sotheby’s Hong Kong on July 8.

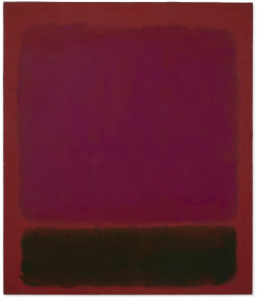

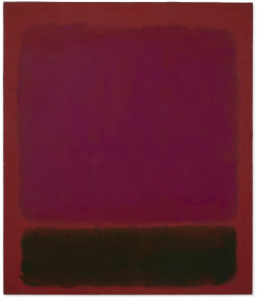

- Untitled (1967)

Mark Rothko

While not Rothko’s highest-selling piece ever (Orange, Red, Yellow sold for $86.9 million in 2012), this one raked in 26 times its previous (1998) $1.2 million selling price.

Final 2020 sale price: $31.3 million at Christie’s New York on October 6.

- The Splash (1966)

David Hockney

In 2006, this acrylic sold at Sotheby’s London for $5.4 million. The price climbed by $26 million in 14 years.

Final 2020 sale price: $31.2 million at Sotheby’s London on February 11.

- Complements (2004 – 2007)

Brice Marden

This diptych, painted between 2004 and 2007, sold for a record amount that makes Marden (at 82 years old) among the 10 most successful living artists.

Final 2020 sale price: $30.9 million at Christie’s New York on July 10.

- Onement V (1952)

Barnett Newman

Part of a group of six paintings, this was Newman’s third best-selling auction result, an $8.4 million increase from its $22.5 million sale price in 2012.

Final 2020 sale price: $30.9 million at Christie’s New York on July 10.

And now… here’s the latest news from the art world: On Thursday, January 28, a Botticelli portrait sold for $92 million, the second-most-expensive Old Master work ever auctioned! Read about it here.