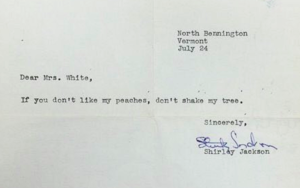

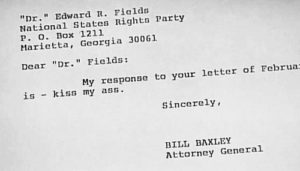

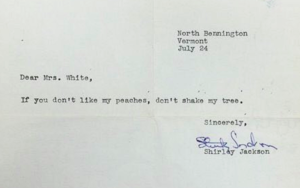

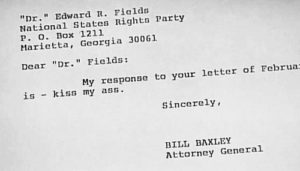

Sometimes a curt reply does the trick. Some examples from LettersofNote.com:

From Shirley Jackson – letter to a disappointed reader, July 24, 1953

Sometimes a curt reply does the trick. Some examples from LettersofNote.com:

From Shirley Jackson – letter to a disappointed reader, July 24, 1953

I’m doing a final revision of my fourth book of poetry…

I’m doing a final revision of my fourth book of poetry. It’s called Now and Then: New and Improved Poems.

I am happy with the title. Is it snarky? I’m not sure. Right now, I like it.

This is probably the 30th revision. For me, poetry is 90% revision. That’s literally true. I checked this last draft against the first. Only 10% of the original words remain.

Some of these poems, as the title suggests, have been published previously. Normally, one doesn’t change a previously published poem. But I did. Over and over again. What’s happened is that some of the poems I no longer recognize as mine. I don’t remember the plots. I don’t recognize the characters.

But that just makes it easier to critique them. They have come from elsewhere. They are newly formed into something apart from me. And that makes the consumption of them more satisfying.

Like the following poem… I am sure my interlocutor was once a real person. I don’t recognize her anymore, but I like the person she became.

Passing the Pink House in Winter

With Unmitigated Joy

What I loved about you then was your profile –

how you were always looking out into some

middle distance. When I would speak to you it

was difficult to know if you were even listening.

It was the side of your face I knew and your

half-amused, half-transported smile. It was

beautiful to see, and impossible to fathom.

It was a lot – a lot more than I was used to – but it

wasn’t enough. We met after the fall and you left at

the end of the winter.

Much later, reading your journal, I discovered how,

when we walked every evening to the gas station to

buy cigarettes and beer, you were thinking about

that sign in front of the pink house, advertising

fortune telling. You said you imagined her customers

to be a menagerie of people like us, “lost souls,

worried about the future.” You said people are like

sailors looking for patterns in a clear night’s sky,

“irradiated by a billion, glittering galaxies.”

I remember one cold afternoon as we passed the

pink house, you noticed a squirrel had made its way

down from a nearby tree, across the snowy yard and

up and onto the sign. It was sitting there looking

back and forth, as if it were worried. You asked me

what I thought it was doing. I said it was doing what

squirrels always do. You asked what that was. I said

I didn’t know. “I guess it’s looking for food.”

In your journal you wrote, “It was then that I

realized the squirrel was somehow the Chosen One.

It had perched on the sign not because it was a sign,

but because it was hungry.” You said that the squirrel

“didn’t need signs, for what it had was hunger.”

You said, “Everything more than that is a burden.

Hunger is enough.”

If I knew then what I know now, I could have told

you that I had that hunger, but it was not enough.

I had a good laugh watching this video of Ben Shapiro’s reaction to Rep. Emanuel Cleaver (D-MO) politically correct prayer at the opening of the 1st session of the 117th Congress on Sunday.

In case you missed it, Cleaver (who is an ordained minister) ended the prayer by saying, “Amen. And A-women.”

Cleaver was making a playful reference to Nancy Pelosi and James McGovern’s proposal of a new rules package regarding the use of “gender-inclusive language” in the House. But Shapiro took him seriously and called it the single stupidest thing he’d ever heard. He explained that the word “amen” is derived from Hebrew via Greek and Latin, and its meaning has nothing to do with men. What he did not explain is that the words “man” and “men” are derived from Old English, have their roots in German, and meant, even back then, “person” and “people.”

The war on words has had a long history of incredibly stupid causes – every bit as stupid as a-woman. That’s because the war on words is a political war, a war for power. And if you are a politician ,you must abide by the golden rule of politics: The ends justify the means.

Number Two Son made fun of my laughter, saying, “Boy, you Conservatives are like snowflakes when it comes to language.”

I said, “As you know from reading your George Orwell, words matter. Words matter because words influence thought. And thought influences political ideas. And political ideas are the keys to power.”

The Tiki hut went up today at Paradise Palms. It’s going to serve as a rest area and wet bar for visitors to our gardens when we open later this year.

Structures like these have been built by the Seminole Indians in Florida since the 16th century – simple shelters that could easily be put up and taken down as the tribes were forced (first by the Spanish colonists and later by the US government) to move from place to place. They called them “Chickees,” their word for “house.” At some point, people began to refer to them as Tiki huts, because they look so much like the thatch-roofed open-sided structures found all over the South Pacific. (“Tiki,” in Polynesian mythology, was the first man created by the gods. Every traditional Tiki hut houses the spirit of one of the gods, usually in the form of a wood or stone sculpture or carving.)

I was eager to meet the crew boss after we settled on the installation date. I had never met a Seminole Indian before. As it turned out, he was not a native Indian. Nor was he a he. The crew boss was a 30-something white woman. And the crew was from Central America.

Notwithstanding the cultural misappropriation, the structure was built quickly and solidly. And after we get a deck on the ground and a bar and some tables and chairs on top of it, we’ll be open for business, if only for ourselves.

“What you get by achieving your goals is not as important as what you become by achieving your goals.” – Zig Ziglar

Becoming and Being

“If you want to be a writer, you have to write. A writer is someone who writes.”

I was 16 years old when my father said those words to me. I was crushed.

Being a writer was all I’d ever wanted to be. And by pointing out the paucity of my literary output compared to the strength of my literary ambition, I felt like he was telling me that I had failed.

I’d written my first poem when I was about 8 years old, and had already decided that I would be a writer when I grew up. It was a single quatrain with a simple rhyme scheme (AABB), titled, precociously and pretentiously, “How Do I Know the World Is Real?”

Although I didn’t know it at the time, my father was a credentialed writer, an award-winning playwright, a Shakespearean scholar, and a teacher of literature, including poetry. I’d often seen him, weekday evenings and weekend mornings, hunched over student essays, muttering and occasionally reading out loud passages to my mother, who would give him a knowing smile.

I don’t remember how I drummed up the courage to show my fragile little poem to him, but I did. And the moment I did, I regretted it. But instead of the negative critique I was expecting, he put his hand on my shoulder, squeezed gently, and said, “You may have a talent for this.”

I wrote poetry and short stories in the years that followed, but I was not, as the cliché goes, obsessed with writing. I had other interests – touch football, the Junior Police Club, a burgeoning interest in girls, etc. As time passed, I wrote less and less. But in my subconscious somewhere, I still yearned to be a writer.

Like most wannabe writers, I rationalized the infrequency of my writing by telling myself that all these other activities were “life experiences,” and that I needed lots of them to become the writer I wanted to be. But in developing this excuse, I was building a structure of self-deception that many people live inside when they abandon their dreams.

I continued to write sporadically throughout my high school and college years. But it wasn’t until the mid 1970s, when I made the decision to take a job with a small publishing company in Washington, DC, that I began to write every day. And every day, my skills improved. If I hadn’t made the effort to take that job, I would have continued, as many wannabe writers do, to tell myself that I was making progress. To write occasionally but publish nothing.

I’ve been writing regularly now for about 45 years. There are still miles between the quality of my writing and that of really great writing, but I have earned a very good living from the writing I do. Good enough to call myself a professional writer.

So many people live their lives failing to become what they want to be because they don’t work on their goal on a daily basis. Whether it is fear or ignorance or laziness, or a bit of all three, they rationalize their lack of commitment with all sorts of seemingly reasonable excuses.

How many times have you heard someone say that they will travel the world or paint paintings or write a book…. one day? And when you hear that, what do you feel? Happy for them because you are confident that one day they will accomplish that long-held goal? Or sort of sad for them because you are pretty sure they never will?

And what about you? What is it that you want to be but haven’t become? What goal or project or task do you keep talking about accomplishing yet never do?

When my father told me that “writers write,” he was saying that I had lost the right to call myself a writer when I stopped writing. But, in retrospect, I can see that he was telling me something else, too – something even more important: I could regain the title the moment I started writing again.

We are at the beginning of another year. It’s as good a time as ever to get to work. You don’t have to give up your day job. You don’t have to put your family in second place. But you do have to begin to practice whatever it will take to become the person you want to be.

There are many impressive styles of Asian Dance, but I bet you’ve never seen an Asian troupe take on the Irish River Dance.

“An expert is someone who has succeeded in making decisions and judgements simpler through knowing what to pay attention to and what to ignore.”

– Edward de Bono

Stock Investing: The 4 Key Metrics I Look at for Future Gains

35 years ago, I was a partner in a profitable business. Every year, my boss/partner and I would sit down and decide how many of those profit dollars we would put in our pockets and how many we would leave in the company for future growth.

Before then, I didn’t even know this was something company owners did. I always assumed that shareholders pocketed 100% of the profits each year. In fact, that’s not possible. Businesses need cash flow to operate current activities, and savings (capital) to invest in new projects and products. If you take out all the profits, it’s nearly impossible to grow.

There is no hard and fast rule for what percentage of profits should be retained and what should be distributed to shareholders. The ratio depends on lots of things: the economics of the business itself (i.e., whether it’s labor or capital intensive, whether it generates or consumes cash, whether the ROIs come quickly or slowly, etc.) plus the growth ambitions and greediness of its owners.

In that long-ago business, there were only two partners: my boss/partner and me. It was, as I said, very profitable. It gushed cash and had no debt. So, in theory, we could take a good percentage of the profits each year. And we did. We typically banked 70% to 80%. This made us personally very wealthy, but it was a bit of a strain on the business – and probably hindered its growth. We peaked at revenues of $135 million.

15 years later, when I took a minor ownership interest in another, similar business, I was shocked to discover that the protocol was to distribute only 10% of the yearly profits to shareholders. This, at first, appalled me. For every thousand dollars of profit we made, our cut was only $100 – of which my partner would get $88 and I’d get $12!

It took a long time to get used to. But, in retrospect, was mostly a smart move. Retaining 90% of the profits allowed us to grow the business without ever borrowing money. And it meant we always had plenty of cash to pay for our mistakes.

That second business grew quite large – to more than 10 times the first one. But eventually we realized that leaving so much cash in the business had an unintended negative consequence: It encouraged a culture with too much financial space for sloppiness and wastefulness. A higher percentage of distribution would have been better.

A third business, which was born out of the second, was developed by a protégé of mine. He distributed a good deal more than 10% of the profits to us, to himself, and to other key players to whom he gave equity. This business had better overall results, both in terms of growth and its eventual value.

So, what does this have to do with investing in public companies? It taught me a lesson about one of the key metrics I use to assess them.

Metric #1: Dividends History

Every business, as I suggested above, has its own internal dynamics. So there’s no such thing as a percentage of retained profits that is right for all industries, let alone all businesses. But I can say this: When I’m looking at companies to invest in – private or public – I like those that are committed to retaining the cash they need to solve unexpected problems and invest in growth, while at the same time distributing profits to shareholders as often and as generously as they can.

It says something important about the company’s management: that it is cautious, not greedy, and yet understands the importance of rewarding stakeholders along the way.

So that is the first of the four metrics I look at when investing in stocks: a history of paying dividends to shareholders. I want to know how often the company pays out dividends… and how much.

Metric #2: Earnings History

With a few exceptions, I want to see a steady growth in revenues. A volatile sales history makes me nervous – especially when I can’t figure out why it’s so erratic. A steady increase in revenues is at least an indication that the people running the business understand how to make it grow. You’d be surprised at how often this is not the case.

The rate of growth is important, too. For small companies, I like to see faster growth. After the first several years, I want to see significant growth – 30% to 50% a year. Then, when the business gets to the $100 million level, I’m happy with 20% to 30%. And when it breaks through the $500 million barrier, I’m comfortable with 10% to 20%.

Occasionally, I make exceptions to these expectations. But only when I can clearly understand why growth was less and how it might recover. If I’m too far away from the business to understand the why and how, I stay away from them.

Metric #3: Recent Sales

The history of earnings is very important, but I also like to see how sales have been doing in the past 6 to 12 months. This is important for the most obvious reason: I want to make sure that something really bad hasn’t happened since the company’s last annual report.

Metric #4: Current Industry Status

In Delivering Happiness, Tony Hsieh compared investing in businesses to playing poker, the only casino game where the odds are not stacked against the player. The most important rule of poker, he said, is what table you are playing at.

If you choose a table that has too many players, it is difficult to win even if most of them are amateurs. If you choose a table with only a few players all of whom are experts, it is difficult, too. The right table is one where your odds of winning are the best, and that is a table where the expert competition is limited.

The same is true with investing. As a general rule, you will do better investing in a solid but unexciting company in a fast-growing industry than you would putting your money into a business with an exciting story in an industry that is going nowhere or is on the decline.

In short, I look for quality in making my stock investments. I look for the quality of the financials, of the management, of the products, and of customer relations. I want to invest in companies that have a proven growth strategy, a sufficient flow of cash, a commitment to employees, customers, and shareholders. And a company that plays a prominent role in an industry that is growing.

But quality is a subjective value. You can’t measure it. But you can measure the history of a company’s dividends, earnings, sales, and its status in its industry. These four metrics won’t insure success in stock investing, but for the typical pedestrian investor like me, they are a very good start.

Here’s a fun app if you want to musically relive your glory days. Just put in the year of your choice and enjoy…

Piranesi

By Susanna Clarke

272 pages

Published September 15, 2020 by Bloomsbury Publishing

I was surprised by how much I liked Piranesi, considering that it is a genre book, fantasy fiction, which I rarely read and even more rarely enjoy. But this one worked. On several levels.

First and most importantly, it has a very simple plot that is based on a simple question: What is Piranesi, the protagonist, doing in this strange place and why? The author, Susanna Clarke, dishes out hints, but sparsely. And there is no great moment of anagnorisis. Not even a denouement, so to speak. And yet, it’s a page turner.

Its themes are expressed as existential and ontological questions that are not so much posed as suggested. And the answers, if you can call them answers, are ambiguous.

But neither the thinness of plot nor the vagueness of thought diminished my enjoyment of the book. I’m trying to figure out why that is.

One reason is the language. The diction is poetic without ornamentation – a kind of restrained prose that makes the many visual descriptions of the castle and its labyrinth come to life. There is a pleasure in reading them that equals what you might get from a James Cameron movie or a Hieronymus Bosch painting.

Several of our book club members had “trouble getting into the first few chapters.” I didn’t experience that – but with the book’s emphasis on prose and imagery, I can understand why they might have. But everyone that persevered (all but one) rated it one of our best books of the year.

From New York Magazine: “Piranesi Will Wreck You: The novel establishes Susanna Clarke as one of our greatest living writers.”

From BookPage: “Almost impossible to put down… lavishly descriptive, charming, heartbreaking, and imbued with a magic that will be familiar to Clarke’s devoted readers, Piranesi will satisfy lovers of Jonathan Strange and win her many new fans.”

From Time Magazine: “Nobody writes about magic the way Clarke does…. She writes about magic as if she’s actually worked it.”