“In gambling, the many must lose in order that the few may win.” – George Bernard Shaw

Bill Bonner on “How the Feds Socialized American Capitalism”

In Raleigh, N.C., there’s a house… or what looks like a house. What’s hidden inside is more important than most people realize.

Lessons From What I Learned Losing a Million Dollars

Part 1: The One Secret That All Successful Money Makers Know and Use

It was the only one left in my audiobook library. I didn’t remember buying it. I’d never heard of it or its authors (Jim Paul and Brendan Moynihan). And the title wasn’t a turn on: What I Learned Losing a Million Dollars.

I mean, really. There are probably millions of businesspeople and investors that could make such a claim. You lost a mere million? Don’t bore me. I want to hear from someone that’s lost a hundred million!

But it was, as I said, the only audiobook in my library. So I began listening to it… and was drawn in.

The first third was a breezy memoir of Jim Paul’s early life, education, and how he rather accidentally became a commodities trader, earning big bucks and living large. Then there was the downfall – a pretty exciting account of going broke and into debt fast.

I almost shut it off there, thinking I’d heard the best part, but I’m glad I didn’t. What followed was an analysis of not just Paul’s pride-bound bad thinking but of the mistakes all investors make sometimes (and some investors make all the time), as well as other insights that rang true.

Paul’s account of his experience is, in part, the story of a smart person that cared more about being right than making money. It is also a portrait of the mortal sins of wealth building: arrogance, ignorance, and greed.

In reviewing the mistakes that led to his million-dollar loss, Paul first examines his trading strategy. Was the strategy wrong? Should he have been using another one?

Then he takes you through a quick review of the strategies of some of the most successful investors of modern times. He demonstrates that each of those strategies was different, and all of them had rules that forbade practices that were followed in the others.

The rules that worked for George Soros, for example, are very different than the rules that worked for Warren Buffett. John Templeton’s strategy worked well for him, but would have not worked for Peter Lynch, and vice versa.

Paul concludes, convincingly, that there is no such thing as a successful trading strategy, and that the search for a winning strategy is a waste of time and money. Instead, he argues that if there is a secret behind the fortunes of Buffett and Soros and the like, it must be something they all did. And when he looked for it, he found it.

The single protocol followed by all of them, regardless of their profit strategies – was about limiting losses.

Paul doesn’t argue that any profit strategy can work. His point is that any profit strategy that isn’t coupled with a loss-prevention strategy is doomed to fail.

I thought about this. And it is true of my experience. Nearly every time I put money into an enterprise without some sort of stop-loss mechanism, I ended up losing most or all of it. And if I look at how I acquired and built wealth over the last 40 years, the strategies that worked all had serious downside protection.

When I consider an investment these days, I spend no more than a moment thinking about the upside potential. I’ve been doing business and investing long enough to know that dwelling on how much money you can make reduces your investment intelligence by about 98%. So when someone pitches an idea to me, I focus my thinking almost entirely on how I can limit my losses if things don’t work out.

There are three ways that I limit my losses:

- I use stoplosses– actual stop losses for stocks or equivalencies for other assets – to close out my position at a predetermined point if the investment goes south and hits my “get-out-now” number.

- I use positionsizing to determine how much I will invest in any given project. This is very powerful, perhaps the most powerful technique for safeguarding and developing wealth. I have a predetermined dollar figure that I will invest in businesses about which I know little, and another for investments about which I know a lot. When you have a modest net worth, that figure might be 5% of it. As your wealth grows, you reduce the percentage. These days, I never invest more than 1% of my net worth in any single investment or business deal.

- I diversify. My investment portfolio consists of real estate (mostly income-producing but some land banking), “Legacy” stocks (large, well-capitalized, dividend-bearing stocks), super-secure bonds (if the yields are decent), private lending (for secured assets), business ventures, options (selling puts on Legacy stocks), and cash.

Scry (verb) – To scry (SKRAYE) is to divine the future or discover secrets, primarily with a crystal ball. As used by Andrew Lang in Cock Lane and Common-Sense: “The antiquity and world-wide diffusion of scrying, in one form or another, interests the student of human nature.”

The word muscle comes from the Latin for “little mouse,” which is what biceps looked like to the early Romans.

“Abducted in Plain Sight” (Netflix).- A documentary series about a child abduction and rape (in 1970s Idaho) that has layers of disturbing elements: Before abducting and seducing/tricking/raping the child, the charismatic criminal sexually seduced both parents, who were then complicit in the abduction.

Have you ever wondered what it would be like to live in a lighthouse? In a storm?

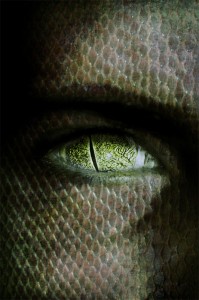

Ego Is Reptilian*

The young woman sitting next to you on the plane is on the phone. She is not whispering. She doesn’t care if you hear her. She says, “Sure, I can go to the gym and work out like crazy and become a ripped bitch. But what does that get me? If you don’t love me for myself, fuck you!”

You smile. You sort of know how she feels. You get an idea about how you will “improve” yourself. Then you get to work on it, but it’s an uphill battle. At some point, you skip a workout or a class or eat an extra slice of pizza and your willpower disappears. You lose ground. You feel anger and shame. And then you decide the problem isn’t you. It’s the ambition.

You know – because you’re not a kid any more – that achieving that goal wasn’t going to give you the good feelings you were seeking. Wellbeing is not about striving for what you don’t have but in being content with what you do have.

All the sages knew that. Socrates, you recall, said, “He who is not contented with what he has would not be contended with what he doesn’t but would like to have.”

Screw those ambitions! They are false roads built by human ego. The better you will come from resisting them, from letting them go. You are going to be happy with how you are – fat or poor or stupid. What does it matter? You’re going to be a Stoic. Or a Transcendentalist. Or a Buddhist!

And there is good reason to support this view. Advocates of acceptance (i.e., opponents of ambition) are correct in pointing out the futility of chasing material goals. They advise letting go of such ephemeral desires, and of desire itself, and seeking spiritual transformation, The true path is a state of consciousness that exists in the here and now. A mindset that dwells neither in the past (depression) or in the future (anxiety) but in the present. “When you realize there is nothing lacking,” Lao Tzu says, “then the whole world belongs to you.”

But this is only half true, for we cannot escape our dual impulses. Even if we do become Stoics or Transcendentalists or Buddhists and commit ourselves to acceptance, we will encounter moments when we feel challenged or threatened or inspired. And when those moments arrive, we react instinctively. Our egos assert themselves. We contract.

This contracting impulse is located, in Freudian terms, in the ego. The ego, in biological terms, resides in two locations: the limbic and the reptilian brain. The limbic brain processes emotional responses. The reptilian brain processes instinctual responses.

A life philosophy that advocates the elimination of limbic and reptilian responses is unrealistic. It is impossible to exterminate emotional responses completely and impossible to eliminate reptilian impulses at all.

One can make impressive progress refining thoughts and even training emotional responses. But one cannot change – not even a bit – one’s reptilian instincts. READ MORE

Temerity (noun) – Temerity (tuh-MARE-ih-tee) is rashness, recklessness, boldness. As used by Emile Zola in Therese Raquin: “There was a sort of brutal temerity in his prudence, the temerity of a man with big fists.”