The young woman sitting next to you on the plane is on the phone. She is not whispering. She doesn’t care if you hear her. She says, “Sure, I can go to the gym and work out like crazy and become a ripped bitch. But what does that get me? If you don’t love me for myself, fuck you!”

You smile. You sort of know how she feels. You get an idea about how you will “improve” yourself. Then you get to work on it, but it’s an uphill battle. At some point, you skip a workout or a class or eat an extra slice of pizza and your willpower disappears. You lose ground. You feel anger and shame. And then you decide the problem isn’t you. It’s the ambition.

You know – because you’re not a kid any more – that achieving that goal wasn’t going to give you the good feelings you were seeking. Wellbeing is not about striving for what you don’t have but in being content with what you do have.

All the sages knew that. Socrates, you recall, said, “He who is not contented with what he has would not be contended with what he doesn’t but would like to have.”

Screw those ambitions! They are false roads built by human ego. The better you will come from resisting them, from letting them go. You are going to be happy with how you are – fat or poor or stupid. What does it matter? You’re going to be a Stoic. Or a Transcendentalist. Or a Buddhist!

And there is good reason to support this view. Advocates of acceptance (i.e., opponents of ambition) are correct in pointing out the futility of chasing material goals. They advise letting go of such ephemeral desires, and of desire itself, and seeking spiritual transformation, The true path is a state of consciousness that exists in the here and now. A mindset that dwells neither in the past (depression) or in the future (anxiety) but in the present. “When you realize there is nothing lacking,” Lao Tzu says, “then the whole world belongs to you.”

But this is only half true, for we cannot escape our dual impulses. Even if we do become Stoics or Transcendentalists or Buddhists and commit ourselves to acceptance, we will encounter moments when we feel challenged or threatened or inspired. And when those moments arrive, we react instinctively. Our egos assert themselves. We contract.

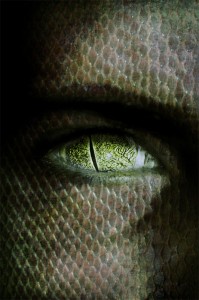

This contracting impulse is located, in Freudian terms, in the ego. The ego, in biological terms, resides in two locations: the limbic and the reptilian brain. The limbic brain processes emotional responses. The reptilian brain processes instinctual responses.

A life philosophy that advocates the elimination of limbic and reptilian responses is unrealistic. It is impossible to exterminate emotional responses completely and impossible to eliminate reptilian impulses at all.

One can make impressive progress refining thoughts and even training emotional responses. But one cannot change – not even a bit – one’s reptilian instincts. READ MORE

When people suffer for a long time or are in great pain, they sometimes wish for death. But should their lives be put in sudden danger, they will respond defensively by instinct.

(You have to wonder whether a possible therapy for depression might be to simulate great and imminent danger.)

To support their claim that it is possible to attain a consciousness that is free of ego, expansionists tell stories of people that have done so. But these are people that no longer exist or whose lives are closed and unavailable for scrutiny.

We may want to believe such stories. But we know, from experience, that they cannot be true. What we do know to be true – from personal experience and from observation – is that some people are naturally more relaxed (less egoistic or less subject to emotional responsiveness) than others. And that some people, through conscious effort, are able to achieve higher levels of emotional relaxation and benefit from that.

But there is no evidence to suggest that anyone can achieve a level of consciousness where the emotions and instinctive responses are non-existent. Homo sapiens, however intelligent, are not able to dissociate completely from their limbic and reptilian brains.

That said, experience teaches us that being relaxed is less painful than being contracted. So that suggests a path we might want to take: a path of progressive relaxation. But we also know that we can accomplish things when we are in a contracted state of consciousness that we could not accomplish if we were relaxed. So to think that the objective of a well-lived life is complete relaxation is foolish, even if it were possible.

In fact, a state of consciousness that is very close to egoless would be a form of mental illness – either a temporary state of semi-consciousness achieved through hallucinogens or a more permanent mental disorder.

There is only way to extinguish the ego: death.

Life is a never-ceasing balancing act between the contraction and the expansion of the ego. Between achieving a relaxed state of mind for comfort and creativity and then being drawn back into egocentricism out of fear or desire.

For those that are naturally relaxed, self-improvement requires discipline – and discipline is a function of a concentrated ego. Relaxed as they are normally, they find they cannot accomplish the things they wish for. They have to exercise their egos so they can have the benefits the ego can provide.

Others – naturally ambitious and/or self-centered people – must work on relaxation if they want to be in the moment and enjoy their lives. These people benefit greatly from relaxation practices (e.g., meditation and yoga) and from social exercises that require them to pay attention to people and things outside of themselves.

Whatever our natures, we must always strive against them – relaxing when we are feeling too tight and concentrating when we are feeling too loose. We should value each of our contradictory impulses equally, for they are equally important. And we should forgive ourselves for them, too. For both of them are good and healthy – two impulses that, when in balance, give us rich and fruitful lives.

* In this series of essays, which hopes to become a book, I’m exploring an idea I’ve been thinking about for a long time: that our knowledge of the universe and our experience of living can be understood by the metaphor of pulsation – of contraction and relaxation. And that such an understanding might be helpful in succeeding in life and accepting death.