I met Ken in 1976 when I was teaching English literature at the University of Chad in N’djamena, Chad. Ken was also on the faculty teaching American literature.

I met Ken in 1976 when I was teaching English literature at the University of Chad in N’djamena, Chad. Ken was also on the faculty teaching American literature.

After my stint Kathy and I moved to Washington DC where I worked as an editor for a publishing business. Ken returned the next year and I found him work as an editor and proofreader. When I relocated to South Florida in 1982 the first person I hired was Ken. He arrived by Greyhound Bus looking — well, you know how Ken often looked.

I took him right to JC Penny’s and bought him three new sets of clothes including three clip-on ties. The next night I helped him find an apartment within walking distance from our offices. For the next five years Ken worked as he always worked: punctually and punctiliously. He was one of about five editors and proofreaders we employed. One of them was, like Ken, an ex-college professor. Another had edited the Chicago Style manual. Ken enjoyed the camaraderie of his colleagues. Back then language correctors like Ken were vital and necessary. This was long before personal computers and spell check programs.

When we sold the Oxford Club to Agora Ken came along as part of the package. I knew he preferred city living to life in the Florida suburbs and he told me later that he was very happy to be living in downtown Baltimore within walking distance of work and his favorite theater on Charles Street and within reach of the ballpark and the library.

Ken was always a very private person. Although we spent lots of time going to movies and arguing about them over beers, I never was able to pry any information about his past. I heard that he was a professor at a university in Missouri and had once been married. He confirmed those two facts but never told me another detail.

Ken was extremely bright and well educated. But during our friendship his intelligence was applied only to movies (he was interested in anything tagged as “grim, stark and depressing,” he once told me) and sports (about which I know nothing) and less frequently about literature and English grammar. Still I always considered him a good friend and I think he felt the same way about me.

During the years I was commuting to Baltimore Ken was part of a very exclusive movie club that met once a week. After I moved to Florida we saw one another only occasionally but when we did it was always cordial and private, just as it had always been.

When Jenny Thompson told me that Ken had lung cancer I came up to visit him and try to persuade him to spend whatever time he had living in our guest cottage where he could be taken care and surrounded by friends of his, the former members of the Florida movie club from so many years ago. If you know Ken you won’t be surprised to learn that he was very agitated by the suggestion. It was way too much of a change for him. He had his own plans — to get him admitted into a hospice that Jenny had mentioned to him. He was equally insistent that he didn’t want chemotherapy. “I’m well beyond seventy,” he told me. (That was the first time he had ever mentioned his age and it was not more specific than that) and I’ve had a good enough life,” he said. “I want to do this my way,” he said.

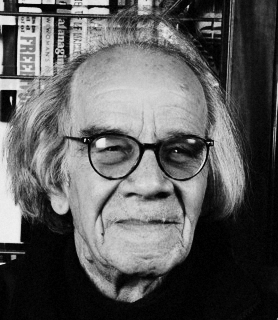

He had — and those of you who know Ken will also appreciate this — a carefully handwritten, eight page treatise which he handed me that provided all the reasons why I should not try to talk him into moving to Florida or having chemotherapy. All his reasons, not unexpectedly, were sound and beautifully expressed. All except one. One of the eight or ten reasons he didn’t want to undergo chemotherapy was that he had “heard that it could make you lose your hair.” As he was reading this sentence to me I couldn’t help but gaze amazedly at the wild outcropping of gray hair mixed with bald patches that constituted his hairstyle that day. But I didn’t argue. There was never any advantage to be had from arguing with Ken.

Last week Alice, who had been kindly taking care of Ken, told me that he was in the hospital after suffering burns and smoke inhalation. His apartment somehow had caught fire. I’ll never know whether the fire was an accident or Ken was just tired of waiting. But he died within a week’s time, which I think he was ready for. Jenny stopped by to see him in the burn unit. She told me he was disconcerted to have visitors but kissed her hand gently and then told her to be damn sure nobody else comes by to bother him.

One final anecdote: in one of my visits with Ken I was attempting to help organize his estate, such as it was. He had, through Agora, a nice sized retirement fund, which he had directed to two old friends from Missouri. So that was fine. He told me he wanted to give me something but the only thing he had was the cash in his savings account that, he said, would be too trifling for “a man of your means.” I told him I thought he should give it to his two friends and he agreed. But the process was very complicated. He would have had to take a trip to the bank that he adamantly refused to do. I figured I would just tell him I had taken care of it and send the money — I figured it couldn’t have been more than a thousand dollars — to his friends and that would be the end of it. Just to be sure I asked him how much he had in the bank. “How the hell do I know?” he shouted. “I put money in there and I pay my bills!” I spent about a half hour sorting through the reams and reams of papers and magazines and bills that filled his living room and found a recent bank statement at last. His account had something like $150,000 in it.