COVID Part Three: A Hugely Harmful Heap of Hogwash!

When the COVID-19 vaccines were first rolled out, they were pitched as a miraculous solution to a global health crisis.

Governments, health officials, and the mainstream media praised them as revolutionary, life-saving, and safe. At the center of this miracle was the mRNA technology. Unlike traditional vaccines, which use weakened or inactivated viruses, the COVID vaccines used genetic instructions to trigger cells into producing just a part of the virus to do the work that weakened and inactivated viruses had done before. This was the spike protein – which was going to teach immune systems to fight off and destroy the virus we came to know as COVID-19.

The rollout of the shots was immediate and nationwide. It was much like the rollout of the polio vaccine at the height of the polio pandemic.

But as the vaccines made their way into the bloodstreams of tens of millions of bodies, reports of serious side effects started to surface. People, including young people who had been healthy and who were considered unlikely candidates for serious side effects from the virus, began suffering from all sorts of surprising and surprisingly serious side effects, such heart inflammation, strokes, and even sudden cardiac arrest.

For whatever reason, these reports were not publicized by the health services that were receiving them. And there was virtually nothing about them reported by the legacy media.

In Part One of this report, I examined how government agencies, the media, and pharmaceutical companies pushed a narrative about the virus and vaccines – the virus was life-threatening, and the vaccines were safe and highly effective. I talked about how the facts that were known then, including the facts known by the WHO, the NIH, and the CDC, seemed to contradict this narrative. But my concerns, along with those of a handful of doctors and scientists saying the same thing, were either ignored or dismissed as “conspiracy theories.”

In Part Two, I examined how this “official” narrative was used to justify the countrywide lockdowns and government mandates that essentially ended the tradition of individual freedom on health issues that had always been the norm in the US. I also touched on the cost of those lockdowns and mandates – in terms of personal liberty, social mobility, and the country’s GDP.

The costs were enormous. And yet the virus was not defeated or even diminished by these authoritarian measures. In fact, it continued unabated until herd immunity kicked in.

From all the standard metrics for determining the effectiveness of mass inoculations and mandatory social protocols, the vaccines had little to no positive effect at all. Meanwhile, the reports of serious side effects continued to mount, including unusual and unexpected deaths – by the thousands.

In this, Part Three of the report, I will tell you what I’ve learned about how the mRNA technology itself contributed to all the war-level death and destruction. I will give you evidence that the original design of the vaccines was flawed from the outset, and how it was never vetted in any serious, scientific way for safety or effectiveness.

I’ll also point out why that was so. Why the incentives made it inevitable. And if you are the least bit open-minded and the least bit skeptical of Trillion-Dollar Industries and the least bit willing to believe that bureaucrats and politicians can be corrupted, you will be outraged at what has taken place and you will never trust Big Medicine, Big Media, and Big Government again.

This is one big, scary story – of how the vaccine rollout became a global disaster that killed and seriously injured millions of people, and of a coordinated network of media, government agencies, and pharmaceutical companies that continued to promote claims that were clearly false, while also concealing crucial negative data and information from the public.

And to be clear: This is not a story about scientific missteps and doing the best “with the information available.” It was a deliberate effort to hide the truth and spin lies whose only benefit was putting billions and billions of net dollars into the P&L statements of some of the largest and most powerful corporations in the world.

1. The Lies and Obfuscation About Vaccine Effectiveness and Safety

When the COVID vaccines first came out, we were told they would prevent infection and transmission. The messaging was clear: Get the shot, stop the spread. But that’s not what happened.

I have found dozens, literally dozens, of substantial, credible studies that came to that conclusion. One, from the UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS), showed that despite one of the highest vaccination rates in the world, COVID deaths didn’t drop as they should have. Instead, during the COVID waves, many of the vaccinated groups that were tracked had higher death rates than many of the groups that were unvaccinated. Steve Kirsch, a data analyst who’s been all over this, pointed to linear regression analysis showing that in some regions, higher vaccination rates correlated with higher death rates.

That study was not an outlier. It was part of a pattern. As the months went by and the booster campaigns rolled out, the data kept showing the same disturbing trend: more shots, more deaths.

Yet, the health narrative coming from most governmental health agencies and the mainstream media didn’t budge.

As the evidence mounted, some of these public agencies, such as the CDC, began quietly walking back their initial claims about preventing infection and transmission. We went from “100% effective” to “effective” to “well, it may not prevent spreading or infection, but it will reduce the chance of severe illness.”

But even that claim had no serious scientific studies behind it. What real evidence that was emerging painted a different picture.

One very important study by the Israeli Ministry of Health revealed that the vaccines’ effectiveness dropped off so quickly that within a few months of getting the vaccination, there was a possibility that the effectiveness was negative. (This is an oblique way of saying that, after several months, you might be more likely to get infected if you were vaccinated.) Let that sink in. Similar data came out of Canada, Australia, and even the US, but it was buried under headlines celebrating the next booster rollout.

Meanwhile, Pfizer and Moderna were raking in billions, while health officials kept pushing boosters.

But for some of the people who had been told the shots would keep them safe, the reality was a lot darker. In this next section, I’m going to touch on how the narrative around vaccine effectiveness was manipulated – and how the health agencies knew early on that the shots weren’t living up to the hype.

2. The COVID Vaccines Were Good for the Hype,

but Bad – Very Bad – for Our Hearts!

When the COVID vaccines first rolled out, we were told that the side effects were non-existent for most and only minor for some. This continued to be the message as the months passed, despite mounting evidence to the contrary – thousands of reports of serious side effects, including prolonged and debilitating conditions, and even death. And not a handful of deaths. Hundreds and then thousands and then tens of thousands.

But we didn’t hear a peep about any of that from Big Pharma, Big Government, or Big Media. Not a peep.

On the contrary, what we heard from these “trustworthy” institutions was that the vaccines were “saving millions of lives.” That’s what they were saying, but there was no “science” behind those claims. They were being made by media bloggers that were using various rhetorical arguments to prove their point. None of those conclusions made their way into reliable scientific journals because they had no basis in the scientific method. And today, they are still being circulated by some people (including Senator Blumenthal in the most recent Senate hearing on the vaccines) who are citing these same completely dismissible sources.

After four years of this charade, however, the truth is coming out. Just last month (April 2025), for example, a massive study involving 85 million people exposed that narrative as false – an egregious falsehood that should embarrass anyone and everyone who advanced that story, including the mainstream press, who – despite having reams of contradictory information available to them – decided to ignore the true science and stick to the official government and Big Pharma narrative.

The study was titled “COVID-19 Vaccination and Cardiovascular Events: A Systematic Review and Bayesian Multivariate Meta-Analysis of Preventive Benefits and Risks.” It was published in the International Journal of Preventive Medicine in April 2025.

It analyzed more than 85 million individuals, including nearly 46 million vaccinated individuals and nearly 40 million unvaccinated (as “control” participants).

The study found “significant increases” in the risks of stroke, heart attack, coronary artery disease (CAD), and arrhythmia following COVID-19 vaccination.

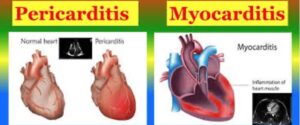

Serious Cardiovascular and Myocardial Risks

The risk of coronary artery disease, for example, was found to be 70% higher overall. And – get this – 244% higher for those who get the jab twice (as recommended).

It would be an understatement to say that these findings have raised concerns among medical professionals. Dr. Peter McCullough, one of the study’s co-authors and a cardiologist who has been reporting on COVID-19 and the vaccines since day one, said, “We are seeing myocarditis at unprecedented rates in young males. This is not rare, and it’s not mild. Some of these young men will suffer long-term cardiac damage.”

One of the many stories I remember reading about was the case of 17-year-old athlete Alex Mitchell, who, just two days after receiving his second mRNA vaccine dose, collapsed during a basketball game and was later diagnosed with myocarditis.

Of course, one example proves nothing. But, as I said, the examples have been in the thousands, and the numbers are still mounting. I thought by now the reports would have been declining, but they haven’t. I continue to get reports like these on a daily basis from a half-dozen blogs that have been following the vaccine story since reports of adverse reactions began coming in.

The mega study, led by epidemiologist Nicolas Hulscher, was clear about the facts. It found “significant increases” in strokes, heart attacks, coronary artery disease (CAD), and arrhythmia following mRNA vaccination. And by “significant,” they meant significant. The risk of heart attack, for example, was up 24% in the six months following vaccination, while arrhythmia rates increased by 18%.

These are not small numbers. And they didn’t just show up in older populations. Many young and otherwise healthy people were among the affected, including athletes and military personnel who had previously passed cardiac screenings with flying colors.

Persistent Spike Proteins and Vascular Damage

A large Japanese study published in 2024 found that the vaccine “spike proteins” continued to create havoc in blood vessels for much longer than the drug promoters has been saying. Dr. Makis, the lead researcher, reported that these lingering spike proteins were causing endothelial inflammation and vascular damage as long as 17 months after the vaccine was given.

“We were told the spike proteins would degrade quickly. That’s clearly not happening,” he said. “This ongoing inflammation is a serious concern, particularly in individuals with pre-existing cardiovascular conditions.”

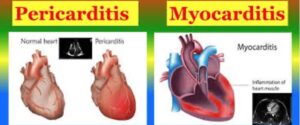

Myocarditis and Pericarditis in the Healthy Young

Myocarditis wasn’t supposed to be a problem. But within weeks of the vaccine rollout, it became clear that young males, particularly those aged 16 to 24, were experiencing myocarditis at rates far above normal.

Hulscher, McCullough, and other researchers conducted a comparative study of the risk of myocarditis after COVID vaccinations. They found that the risk of myocarditis was higher among those who had received the COVID vaccine than among those that had not.

The study was so large, so comprehensive, and so definitive that Dr. McCullough called for an immediate withdrawal of mRNA vaccines until more comprehensive safety studies could be conducted.

“We are seeing myocarditis at unprecedented rates in young males. This is not rare, and it’s not mild. Some of these young men will suffer long-term cardiac damage,” he warned.

Sources:

1. Hulscher, N., Cardiovascular Risks of mRNA Vaccines: A Nationwide Study, April 2025

2. McCullough, P., Rose, J., Makis, R., Comparative Study on Myocarditis Rates Post-Vaccination vs. Post-Infection, Journal of Cardiology, March 2025

3. Makis, R., Vascular Persistence of Spike Proteins Following mRNA Vaccination: Implications for Cardiovascular Health, Japanese Journal of Vascular Research, Dec. 2024

The Dirty Trick Behind Vaccine “Effectiveness”

In the Czech Republic, unvaccinated individuals were required to undergo mandatory COVID-19 testing, often twice a week, while vaccinated individuals were exempt.

This differential testing policy skewed the data, making the vaccines appear highly effective by disproportionately testing the unvaccinated.

Steve Kirsch asserts that similar testing policies were implemented in many countries, distorting efficacy data globally.

The logic is simple:

If the unvaccinated are constantly tested and the vaccinated are not, more COVID cases will naturally be found among the unvaccinated, artificially inflating the vaccine’s apparent effectiveness.

Kirsch contends that the only honest measure of vaccine impact is to compare all-cause mortality rates between vaccinated and unvaccinated groups over the entire study period. His calculations suggest that when this is done, the vaccines were not only ineffective but potentially deadly across age groups.

3. Some Vindication from Recent Disclosures

Although the mainstream press has been virtually silent about it, there have been other corrective measures and responses to all the deception and damage done by those that pushed the pro-vaccine narrative.

For example:

* Resignation: Peter Marks, the FDA’s top vaccine regulator, resigned on April 15, 2025, amid growing controversy over his decision to approve COVID-19 boosters for infants. Critics argued that the approval was based on limited data and ignored emerging evidence of serious side effects. In his resignation letter, Marks acknowledged the pressure to greenlight the boosters, saying, “The pressure to approve was immense. I did what I could to balance the science with the political and media pressure, but in hindsight, it was not enough.”

* Collusion Exposed: According to a whistleblower complaint filed in federal court on March 12, 2025, the FDA and Pfizer allegedly conspired to delay the release of clinical trial data until after the 2020 presidential election. The complaint, filed by former FDA analyst Daniel Harper, claims that key data showing a higher-than-expected incidence of myocarditis and pericarditis in young males was buried under pressure from top executives at Pfizer. “They knew. And they hid it. And they pushed it anyway,” Harper said in a sworn affidavit. The case is ongoing.

* Big Pharma’s Hold on the NIH and CDC: Recent reports from investigative journalist Nicholas Hulscher reveal a pattern of financial ties between vaccine manufacturers and senior officials at the NIH and CDC. Hulscher’s investigation, published on April 30, 2025, shows that both agencies received millions in “donations” from Pfizer, Moderna, and J&J, raising serious questions about conflicts of interest. In one particularly damning email exchange, a senior CDC official wrote, “We need to make sure our messaging aligns with the pharmaceutical partners.”

Sources:

1. Marks, P., Resignation Letter, FDA, April 15, 2025

2. Harper, D., Whistleblower Complaint, Harper v. FDA, Federal Court Filings, March 12, 2025

3. Hulscher, N., Big Pharma’s Influence on Public Health Agencies, Courageous Discourse, April 30, 2025

On June 8, 2022, Israeli Ministry of Health officials met with scientists to discuss COVID vaccine adverse events. The meeting was secretly recorded and published on Rumble by Israeli journalist Yaffa Shir-Raz.

Here is some of what was acknowledged to be true by the participants but never found its way to the general population until now:

* Ministry officials acknowledged that vaccine effectiveness against infection dropped to negligible levels after just a few months.

* Some data suggested potential negative effectiveness (higher infection rates in vaccinated individuals) after 4-6 months.

* Officials admitted they had no long-term safety data despite mandating multiple boosters.

The meeting included a discussion about how to present this information to the public without undermining the vaccination campaign.

The Bottom Line

The Israeli Ministry of Health had evidence by early 2022 of:

* Rapidly waning or absent protection against infection,

* Serious and persistent adverse events, including neurological and immunological conditions,

* No structured long-term safety follow-up, and

* A coordinated effort to control how the data was framed rather than re-evaluate the vaccination campaign.

Despite these concerns, the Ministry continued recommending and mandating booster doses.

And so did the CDC!

4. Despite Mounting Evidence of Harm, Media Censorship and Propaganda Has Continued

As I pointed out in Parts One and Two of this report, since the virus began, there has been a handful of doctors, scientists, and journalists who have questioned the “highly infectious and deadly” narrative being pushed by the pro-vaccine cartel.

And just about every one of them that had more than a thousand social media followers faced censorship, libel, threats, and, in some cases, professional and legal recriminations.

A few of at least a dozen prominent examples:

* Dr. Peter McCullough, one of the most prominent critics, had his Twitter account suspended in January 2025 after posting about myocarditis cases in young athletes. “They don’t want us talking about the side effects because they know it undermines their entire narrative,” McCullough said in a podcast interview.

* Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, a professor of medicine at Stanford University, co-authored the Great Barrington Declaration, advocating for focused protection of vulnerable populations rather than widespread lockdowns. He questioned the severity of COVID-19 and the efficacy of lockdowns, leading to substantial criticism from the scientific community. Bhattacharya’s views were labeled as fringe, and he faced professional ostracism, including being placed on a Twitter “Trends blacklist,” which limited the visibility of his posts.

* Dr. Paul Marik, a critical care physician and co-founder of the Front Line COVID-19 Critical Care Alliance (FLCCC), promoted alternative treatments for COVID-19, such as ivermectin. He faced professional repercussions, including the retraction of his research papers and disciplinary actions from medical boards. Marik’s hospital privileges were revoked, and he resigned from his position at Eastern Virginia Medical School amid the controversy.

* Paul D. Thacker, an investigative journalist, reported on alleged conflicts of interest within the pharmaceutical industry and regulatory agencies. His articles, including a piece in The BMJ highlighting issues in Pfizer’s vaccine trials, drew criticism from some in the scientific community who accused him of promoting anti-vaccine sentiments. Thacker faced professional challenges, including being labeled as a conspiracy theorist and facing pushback from colleagues and institutions.

* Investigative journalist Sharyl Attkisson reported that her COVID vaccine coverage was “shadowbanned” on multiple platforms, including Facebook and YouTube.

5. The Legacy Media Was 100% Complicit in the Deception

Despite a flood of evidence of serious vaccine side effects, mainstream media outlets have continued to downplay or ignore the data.

I don’t have the time and you don’t have the patience to go through all the examples of this silencing and propaganda campaign, but here are some of the dozens I’ve found:

* NBC: In April 2025, NBC ran a segment titled “COVID Vaccine Myths and Facts,” in which they claimed that reports of myocarditis in young males were “extremely rare.” However, data from the CDC itself contradicted that statement, showing rates of myocarditis that were far higher than the baseline, especially in young males aged 12 to 24.

* Bloomberg: In Feb. 2025, Bloomberg published an op-ed demanding that platforms like Substack and Rumble be held accountable for “promoting vaccine misinformation.”

* Dr. Aaron Kaplan claimed that allowing vaccine skeptics to publish unverified claims was a “public health risk.” Kaplan specifically targeted Substack, which had become a hub for dissenting voices like Dr. Robert Malone and Steve Kirsch.

* Journalist Matt Taibbi pushed back, arguing that the real danger was the suppression of legitimate scientific debate. “If the only voices we’re allowed to hear are those approved by Big Pharma, how can the public make informed health decisions?” Taibbi wrote on Substack.

* Twitter: A former New York Times reporter, Alex Berenson became a prominent critic of COVID-19 vaccines, often appearing in right-wing media to share his views. He claimed that the vaccines were “dangerous and ineffective,” leading to his permanent suspension from Twitter in August 2021 for violating the platform’s COVID-19 misinformation policy. Berenson later sued Twitter and was reinstated in 2022 after reaching a settlement.

* PayPal: British journalist Toby Young faced backlash for his articles downplaying the severity of COVID-19 and questioning vaccine efficacy. In 2020, the UK’s press regulator ruled that one of his articles was “significantly misleading.” Later, in 2022, PayPal suspended accounts associated with Young, including The Free Speech Union and The Daily Sceptic, citing violations related to COVID-19 misinformation. These accounts were reinstated after public outcry.

* Twitter: An American academic and signatory of the Great Barrington Declaration criticized COVID-19 vaccines, particularly highlighting concerns about myocarditis. He was suspended from Twitter after multiple violations related to COVID-19 misinformation.

And finally…

* All the smugly ignorant liberals: When Trump picked Robert F. Kennedy Jr. for Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, it seemed like the entire Liberal and Leftist press, along with every House and Senate Democrat, went ballistic, accusing Kennedy of being unqualified, an “anti-vaxer,” and a conspiracy theorist, particularly because he has long called for studies to investigate the very substantial correlative relationship between the emergence of vaccines and the rise in cases of autism. If you didn’t see the confirmation hearings, you should watch a few of them. RFK embarrasses and humiliates his critics by showing them, again and again, that he knows the science and they don’t.

Sources:

1. Kaplan, A., Why Platforms Must Stop Promoting Vaccine Misinformation, Bloomberg, Feb. 15, 2025

2. Taibbi, M., When Censorship Becomes a Public Health Hazard, Substack, Feb. 20, 2025

3. McCullough, P., Podcast Interview, Myocarditis and Censorship, March 2, 2025

4. Attkisson, S., COVID Vaccine Coverage and Social Media Censorship, SharylAttkisson.com, Jan. 18, 2025

5. NBC News, COVID Vaccine Myths and Facts, April 4, 2025

6. New Discoveries of Long-Term Harm

Over the past 12 to 18 months, as it became more and more difficult for the vaccine promoters to continue claiming that the vaccines were “safe and effective” – or even that they reduced serious illness – they went quiet on the issue and focused their efforts on quashing the reports that the vaccines were doing harm – serious, long-term harm.

While short-term side effects like injection site pain, fatigue, and fever were widely acknowledged, more serious long-term side effects have begun to surface – side effects that were initially dismissed as “rare” or “unproven” but are now demanding urgent attention, including autoimmune disorders, cancer, neurological conditions, and a cluster of symptoms increasingly referred to as “Post-Vaccination Syndrome.”

Autoimmune Disorders

Reports of autoimmune conditions such as Guillain-Barré Syndrome, lupus, and myocarditis have become more common among vaccinated individuals. A study by the Mayo Clinic published in February 2025 indicates a 34% increase in autoimmune diagnoses post-vaccination, with the highest risk observed in young males under 30.

Dr. Peter McCullough, whom I’ve cited above and who I believe is not only one of the best-known experts on the negative effects of the vaccines, but also the most qualified in terms of experience, is now warning that “the autoimmune response generated by the spike protein appears to persist for months, potentially triggering chronic conditions that may not resolve.”

Very Scary: The “Turbo Cancer” Phenomenon

One of the most alarming discoveries is the potential link between mRNA vaccination and aggressive cancers, colloquially referred to as “turbo cancers.”

Unlike conventional cancers that typically develop over years, these aggressive malignancies appear to progress rapidly post-vaccination.

According to a May 2025 article in Focal Points, pathologists in the US and Europe are documenting an uptick in unusual cancers, including glioblastomas, lymphomas, and pancreatic cancers, particularly in younger, previously healthy individuals.

Dr. Angus Dalrymple, an oncologist with over 20 years of experience, stated, “We are seeing an unprecedented rate of rapid-onset cancers that defy the usual staging and progression. The only common factor in most of these cases is recent mRNA vaccination.”

Neurological Dangers and Complications

A Yale study published in April 2025 has identified a cluster of neurological symptoms now being classified under “Post-Vaccination Syndrome.” Symptoms include severe headaches, cognitive decline, vertigo, and memory loss. The study found that individuals with prior neurological conditions were at higher risk, but even healthy individuals were developing debilitating symptoms months after vaccination. The report also notes that the spike protein’s persistence in the central nervous system could be the underlying cause.

Just the Facts

Okay, I’m going to stop here.

As you know, I’ve spent a lot of time over the last four years clipping and filing stories and studies about the virus and the vaccines and the outright lies that were sold to the American public. By publishing this three-part report here – a summary of everything I discovered – I hope I’ve persuaded you that the mRNA COVID vaccines were not just ineffective, but that they had many serious, life-threatening side effects – and that the public should have heard about them years ago, when they were first reported.

In the complete monograph that I’m going to be publishing, I will provide a lot more evidence for every claim I’ve made. But since your eyes are probably glazing over right now, I’m going to end here with eight facts that I believe are indisputable.

Eight Facts We Now Know about the

Safety and Effectiveness of the COVID Vaccines

1. The mRNA Vaccines did not prevent infection or transmission. Real-world data shows vaccinated individuals still catch and spread COVID, often at similar or even higher rates than the unvaccinated.

2. From the beginning, the CDC and the FDA failed to warn the public about internal reports about dangerous vaccine side effects. FOIA-released emails and whistleblower reports show adverse events were downplayed or ignored.

3. The vaccines offer no demonstrable reduction in all-cause mortality. Randomized trials from Pfizer and Moderna showed no statistically significant mortality benefit compared to placebo. (This should have been a flashing light to the CDC. See Fact #8.)

4. Risk of myocarditis, especially in young men, is well-documented and sometimes fatal. Multiple studies have confirmed this, including military datasets and insurance claim reviews.

5. Spike protein persistence and distribution is greater than claimed. Studies have found vaccine-induced spike proteins lingering in the bloodstream and even penetrating organs for weeks or months.

6. Post-vaccine complications have included strokes, clotting disorders, and sudden deaths. Many of these are under investigation and have not been adequately explained by authorities.

7. There is evidence of DNA plasmid contamination in mRNA vials. This may pose theoretical long-term risks and violates regulatory manufacturing standards.

8. The vaccines almost certainly killed people – possibly millions of people. All-cause mortality went up – significantly – after the vaccines were rolled out. That should never happen. When it does happen, it means that something – and most likely the vaccine – is causing all the extra deaths. In addition to all-cause mortality, more specific studies are being published that show direct links between vaccinations and deaths. One recent study in Florida found a 36% increase in non-COVID death after mRNA vaccination. Especially among young men, this increase in all-cause mortality should have triggered immediate concern and further investigation.

Final Thoughts: I’m Disgusted. You Should Be Too…

Just last week, as I was editing this for the last time, I discovered that Senator Ron Johnson was running Senate Hearings on the narrative that the COVID vaccines were “safe and effective.”

It was a bloodbath for Big Pharma, Big Media, and the politicians that tried so desperately to try to convince voters that (a) the virus was really, really infectious and really, really lethal (both wrong) and (b) the COVID vaccines that were so quickly created and so unconstitutionally mandated were both safe and also effective.

There has always been a ton of evidence disproving both of these narratives. But so long as the Democrats were in control of HHS, the NIH, the CDC, and the FDA, that information was not leaving the vaults it was stored in. (Remember, fear of the virus was perhaps the most significant reason that Biden got elected in 2020.)

Now that the Republicans have the keys, the documents are coming out. And they are as bad as I thought. They reveal that the CDC knew about the heart risks, including serious myocarditis tied to the Pfizer vaccine as early as February 2021 – but said nothing to the public. And they show that they also had the data and the conclusions from Israel and the Department of Defense that made it quite clear that the vaccines were not saving lives, but ending them.

They knew, too, that VAERS, the reporting agency for adverse reactions to the vaccine, had accumulated nearly 3,000 post-vaccine deaths, almost half of which occurred within 72 hours of injection!

Instead of sounding the alarm and halting the vaccinations immediately, they issued a milquetoast set of “new guidelines” that were designed to be ignored and were.

Senator Johnson’s Senate Hearings on the vaccines have been a shitshow.

OB-GYN Dr. James Thorp presented data suggesting that miscarriage rates for women vaccinated during the first trimester may have been as high as 82% – figures the CDC ignored. He also cited animal studies showing a 60% destruction of ovarian reserve in rats. If true in humans, the implications for fertility are catastrophic.

Dr. Peter McCullough testified that he’s now treated thousands of patients with vaccine-induced myocarditis – something he had seen only twice in his entire career before COVID. He cited cases of healthy teenagers dying in their sleep days after injection and slammed public health officials for failing to respond to clear warning signs.

Dr. Jordan Vaughn provided testimony that up to 15 million Americans may now be living with long COVID or post-vaccine injury.

He described widespread spike protein damage detectable in patients more than 700 days after their last shot – despite initial claims the protein stayed in the arm. “We didn’t just inject people,” he said. “We turned them into spike protein factories.”

Attorney Aaron Siri offered a brutal reminder that vaccine makers enjoy blanket liability protections under the 1986 National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act – and therefore no financial incentive to make vaccines safer. “They don’t have the incentive,” he said. “In fact, they have the disincentive.”

Senator Johnson displayed a devastating chart showing that COVID cases and deaths actually spiked after vaccine uptake became widespread in 2021. If the vaccines worked, the numbers would have dropped. They didn’t.

Still, as the narrative collapses, defenders like Senator Richard Blumenthal are already retreating to an old script: “We did our best with the information we had at the time.”

When I was writing about this four years ago, I predicted this day would come. I said that I was sure the truth about COVID would eventually come out and I hoped that when it did, the malefactors behind the propaganda would not be taken seriously when they said, “We were working on the best information we had at the time.”

I figured out that this whole thing was a crock of shit back then just by doing a little math.

The incredible damage in terms of lives, culture, education, and wealth that was destroyed was not caused by honest mistakes made in the fog of crisis. They were lies, deliberate and sustained, propped up by government officials, media personalities, and a complicit medical establishment.

And most of those who believed the lies still aren’t ready to admit they were deceived – because that would mean admitting they were naïve and that it was they who didn’t “follow the science.”

This horrific story is hardly over. On the contrary, it’s only the first few pages that have so far been written. How much we will eventually know about who was behind this – the individuals in charge, not the institutions (we know them) – is impossible to say.

The grift is so large. The money is so great. The secrets are so incendiary. The only thing I feel certain about is that if Kamala Harris were president now, this entire debacle would already be yesterday’s conspiracy theory.

Sources:

1. Goldberg, Y., et al, Waning Immunity after the BNT162b2 Vaccine in Israel, NEJM

2. Kirsch, S., Data on COVID-19 Vaccine Mortality Trends

3. Hulscher, N., Cardiovascular Risks of mRNA Vaccines: A Nationwide Study

4. Office for National Statistics (UK), Deaths involving COVID-19 by vaccination status, England

5. Makis, R., Persistent Spike Protein Effects Post-mRNA Vaccination

6. McCullough, P., Rose, J., Myocarditis Post-Vaccination Analysis

7. Yale School of Medicine, Post-Vaccination Syndrome Neurological Study

8. Florida Department of Health, Brand Differential Study on mRNA Vaccine Mortality

9. Focal Points, Turbo Cancers and COVID-19 Vaccine Link

10. Taibbi, M., On Media Suppression and Vaccine Discourse

11. Attkisson, S., Shadowbanning and Vaccine Coverage

12. Harper, D., Whistleblower Report Filed March 2025

13. Marks, P., Resignation Letter from FDA, April 2025

14. CDC Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS)

15. NIH Conflict of Interest Disclosures, 2024–25

16. Nature Biotechnology, mRNA Vaccine Development under EUA: The Fast Track Risks, Jan. 2022.

17. Clinical Research in Cardiology, Sudden Cardiac Death and mRNA Vaccine Exposure, March 2023

18. OneAmerica Life Insurance, CEO Statement on Mortality Rates, Jan. 2022

19. BMJ, Poor Practices in Pfizer’s Vaccine Trial Sites, Oct. 2021

20. German BKK Insurance, Adverse Event Undercounting in COVID Vaccine Reporting, Feb. 2022

21. Columbia University Pathology, Myocarditis Autopsies Post-Vaccination, Dec. 2022

22. Ministry of Health, Japan, Spike Protein-Associated Pericarditis Advisory, March 2024

23. Oxford University, Short-Term Booster Efficacy and Rapid Decline, July 2022

Worth (Further) Reading

As I said, this is a story that is just beginning to be told. Here are five new depressing and highly disturbing revelations that I found within the last 24 hours:

1. Welcome to the cover-up for the cover-up

By Alex Berenson

“Are Joe Biden and his handlers telling the truth about his prostate cancer diagnosis? The way they’ve tried to hide his cognitive decline gives us reason to ask hard questions.” Click here.

2. Unheard of: So Many Young People with Heart Failure

By Peter A. McCullough, MD, MPH

“One of the most alarming aspects of the pandemic for me as a cardiologist is to see young people develop heart failure because of COVID-19 vaccine myopericarditis.” Click here.

3. Many with Serious Reactions from the Vaccine Die Quickly

A new, retrospective cohort study on COVID vaccine-related deaths found that nearly half of those with serious side effects died within 42 days of being vaccinated. The Korean government-backed study, published in PLos One, found that out of 358 patients who suffered severe SAEs post-vaccination, 160 died within 42 days, yielding a 42-day case-fatality rate of 44.7%.

You can read more about it here.

4. Biden Adm.: “Criticism of COVID Mandates Is Doctrine of Violent Domestic Extremists”

By John Leake, Focal Points

Director of National Intelligence, Tulsi Gabbard, just declassified a 13 December 2021 National Counterterrorism Center memo warning that Domestic Violent Extremists “will threaten to mobilize to violence in opposition to new or expanding COVID-19 related mandates.” Click here.

5. Highlights from The Corruption of Science and Federal Health Agencies

By Peter A. McCullough, MD, MPH

How health officials downplayed and hid myocarditis and other adverse events associated with the COVID-19 vaccines. Click here.